Drain-spotting: The people who keep their minds in the gutter

- Published

Tour guides usually urge people to "look up!" when exploring a city, but a downwards glance can also offer portals into the unknown. Like bellybutton piercings of the streets, the gleam of these cast-iron discs are little glimpses of jewellery not usually seen.

Manhole covers, coalhole covers and drain covers all offer access to an underground world that, if not exactly thrilling, is at least full of artistry, history and in many cases, beauty.

Dr Shepherd Thomas Taylor, who studied medicine in 1860s London, is the first person known to have captured their charm.

Having a poetic turn of phrase and being handy with a sketching pencil, the doctor described "these discs and squares" as "like abstract flowers in an otherwise arid field, bringing a note of flippant gaiety into the often depressing city surroundings".

Unlikely though "flippant gaiety" sounds as a reaction to seeing a drain cover, the noted academic on internal cancers was at least having a break from the grim nature of his studies by taking his pavement-staring strolls.

In a similar vein, many people shuffling about London on their government-sanctioned hour of lockdown fresh air and exercise might have been more likely to look down as they contemplated how life had changed over the past year or so.

"I'm sure I heard a rumour of an original Pantametallurgicon cover round here"

A hobby of which Jeremy Corbyn is the most high-profile fan, operculism (from operculum, the grid-like series of bones that cover a fish's gills) does not tend to attract many adrenaline junkies. The Dull Men's Club, external (motto: Celebrating the Ordinary) is an enthusiastic curator of various manhole appreciation publications.

Amir Dotan, who lives in Stoke Newington, north-east London, has been a fan of coalhole covers since he moved to the district in 2002. He has patrolled the streets and recorded more than 100 designs, as well as beginning to accumulate his own: "You start photographing coalhole covers and before you know it you have a collection of five lined up in your back garden."

Some of the designs collected by Amir Dotan, whose talks are not at all boring

Coalholes, drains and manhole covers

Drain-spotting is a fairly broad church; some worshippers enjoy manhole covers, the interest of others is piqued by coalhole covers and still more get their thrills from drainage grilles.

Coalhole covers can be found outside front doors, pavements and front paths. Often ornate, the cast-iron discs are usually 12in (30cm) in diameter and were designed to let the coalman deliver coal into a cellar through a chute, without needing to enter the house

A manhole cover is a removable lid over a hole large enough for a person to pass through. The hole goes into a vertical circular pipe, an access point that allows inspection, maintenance and repairs

A drain grid is the grille that covers the drain hole, and can bear details such as a date or a manufacturer's name

Source: Fabricated Access Covers Trade Association (obviously)

Mr Dotan, who has made a podcast for the BBC series The Boring Talks, points out he, Mr Corbyn and Dr Taylor are not alone in this somewhat niche pastime.

The drawings made during Dr Taylor's perambulations sparked enough interest that a book was published in 1929, when the venerable doctor was aged 90.

Opercula, which was reissued in various editions, is not still in print, but copies are still available second-hand, or you can read it online, external.

Dr Taylor writes dreamily of coalhole covers with designs "as delicate as snow crystals" and muses on the nature of creativity and change: "Perhaps it is because the metal itself, with the constant wear and tear from walking, running or shuffling feet moving on its surface, acquires an accidental beauty that no pattern, however unnecessary or over-elaborate, can add to or take away."

The doctor's papers, including diaries and notebooks on internal cancers are held at the Royal College of Physicians, external.

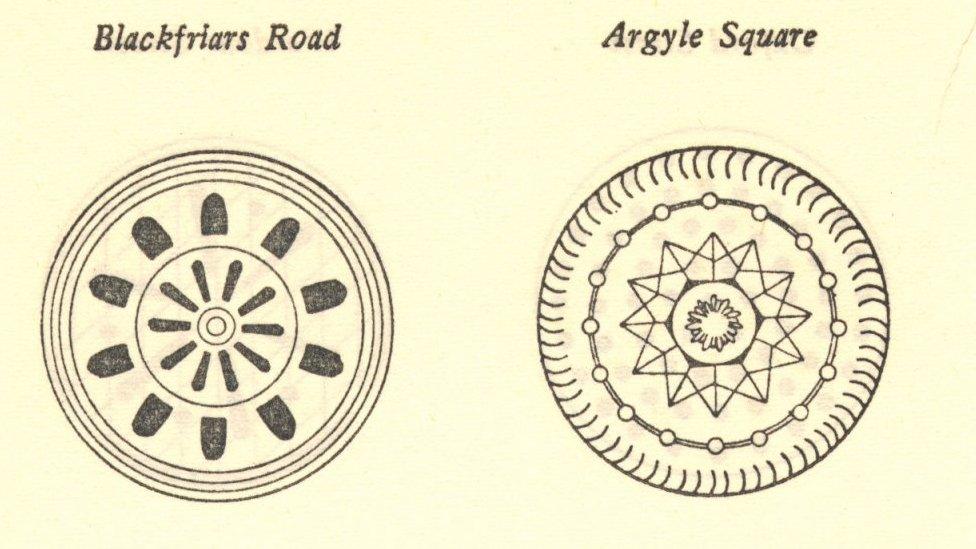

Two of the manhole covers recorded by Dr Taylor in his book Opercula

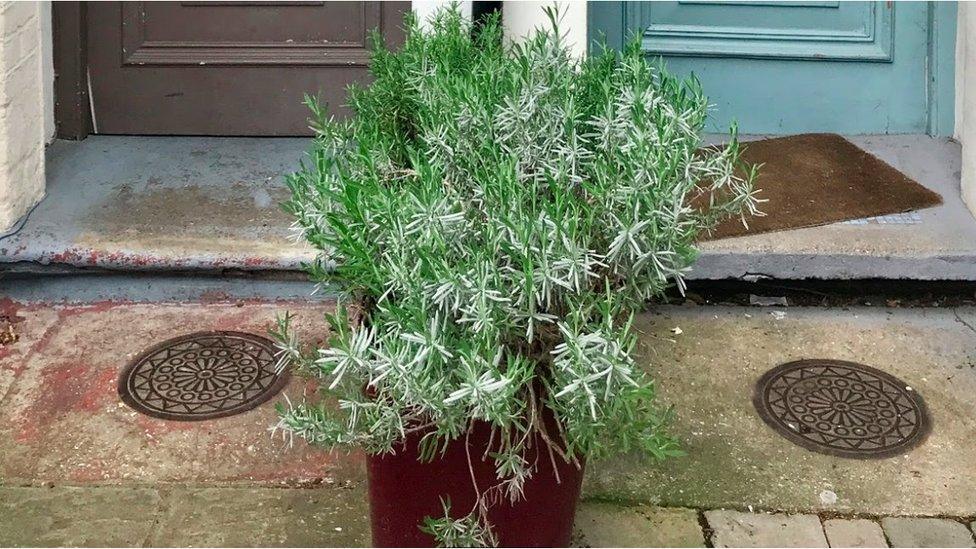

Stoke Newington's coalhole covers were an irresistible draw for Amir Dotan

When not exhorting bombs to drop on Slough, Poet Laureate Sir John Betjeman was an enthusiastic operculist. His statue at St Pancras railway station stands on a giant drain-cover-like rondel. Appropriately, on the right, he laughs like a drain

Dr Taylor's quest to find alloyed artefacts was helped by the fact he was alive at the time when almost anything that could have - from bridges to chessmen to coffins to urinals - had a version that was cast in iron.

A century later, an article published in a newspaper in the US claimed Britain was still "full of operculists" - despite the fact that the public's fascination with iron was fading away. However, making rubbings was still popular enough for special equipment to be sold to accommodate the inveterate drain-spotter (presumably a nicely packaged set of paper and a crayon).

Victor Musgrave, a cravat-wearing British poet, art dealer and curator had a collection - he exhibited his favourite 40 in Soho in 1962.

Fellow (and better-known) poet John Betjeman took a break from having a go at Slough and spoke at the opening of the event, appreciating the design of the covers and lamenting their disappearance from the capital's streets.

Victor Musgrave daydreaming about drain covers

Victor Musgrave having spotted a drain cover

Other stories you might enjoy:

Graphic designer Marina Willer created a booklet of neon rubbings for the London company Pentagram celebrating these "enduring examples of industrial design"

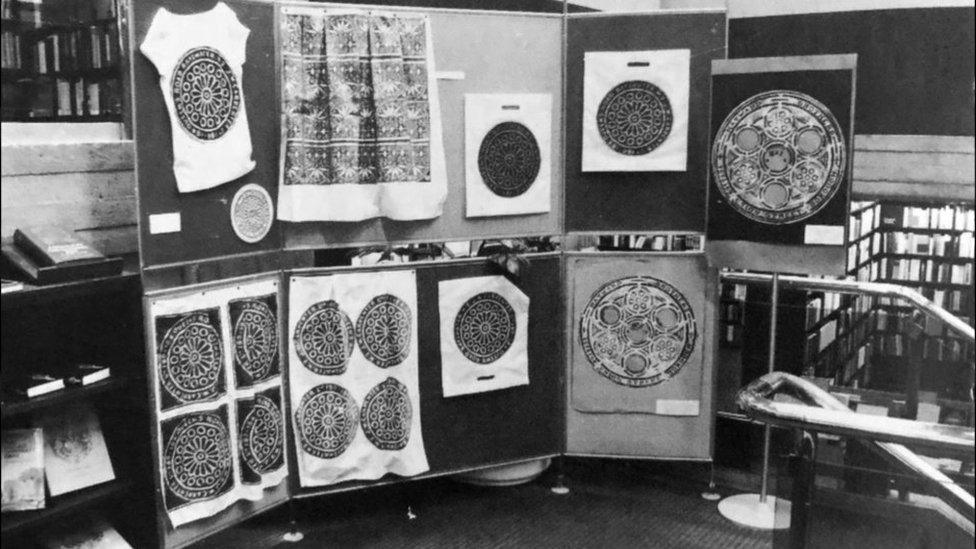

Since then, the decorative shields have continued to prove an inspiration to artists, featuring in textile designs by Lily Goddard in the 1970s and Emma-France Raff , externalin the present day.

In 2016 graphic designer Marina Willer created a booklet of neon rubbings; manhole colouring books are available for people seeking mindfulness; and a Shoreditch company offers framed prints of rubbings for £80.

In the mid-late 1970s, textile designer Lily Goddard incorporated coalhole patterns in her work, printing rubbed images on to fabric and exhibiting in both 1975 and 1978

In 1995 an artist called Keith Bowler was commissioned to produce coal hole-style metal roundels depicting something of significance to their location.

Works include four tankards surrounding a heraldic bird of prey outside the Black Eagle Brewery on Brick Lane and matchstick men mark the location of the hall on Hanbury Street where Bryant & May's match girls met and formed a trade union.

Not a coal-hole cover

And amateur operculists should bear in mind not everything is as it seems - a Londoner who goes by the name of the Gentle Author, who documents existence in the East End with his website Spitalfields Life, external, tells a tale of Bowler overhearing a tour guide explaining the plaques were installed in the 19th Century for people who could not read.

The guide was reluctant to believe they were actually artworks designed on Bowler's kitchen table.

The Gentle Author's interest in Bowler's work also spurred him to look for the original ironworks, and he photographs and comments upon his favourites.

"So much wit and grace applied to the design of a modest coalhole cover - it redefines the notion of utilitarian design," he says.

"Even neglected and trodden beneath a million feet, by virtue of being in the street, these ingenious covers remind us of their long dead makers' names more effectively than any tombstone in a churchyard."

And so as London reopens and Covid restrictions are eased, it might be a good time to take to the pavements of the capital and look down before we look up again.

Also not a coal-hole cover

"Undoubtedly the most snazzy in the neighbourhood," says the Gentle Author about this one from the 1880s in Fournier Street

Tips on drainspotting

Many manufacturers can be found fairly easily - Hayward Brothers, William Pryor & Co, John C. Aston & Son, and Jones & Co. are all common. But there are others - such as the Pantametallurgicon company - which are incredibly rare.

The Institute of Historic Building Conservation, external says there is only a single surviving Pantametallurgicon cover, on Sloane Street in Knightsbridge.

There are many other individual ones worth seeing, including:

This memorial to a 130-ton yellow-white mass of oils, fat, grease and rubbish blocking up the pipes in the Victorian tunnel beneath Whitechapel.

The site of 2017's gigantic fatberg - find it where the pedestrianised Court Street meets Whitechapel Road, just before the crossing

This reminder of the Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company which has the dubious honour of being a super-spreader of cholera:

A Dr John Snow had a hunch that water was involved with the disease and compared the death rates in the districts supplied by the Lambeth Water Company, which piped water in from Surbiton, and the S&V, which piped it from the foetid Thames.

Areas supplied by the S&V had a death rate nine times higher than those supplied by the Lambeth company.

Arthur Hassall, in his 1850 book, Microscopic Examination of the Water Supplied to the Inhabitants of London (if your local library's copies are all checked out, the 60-page thriller can be read here, external) wrote of the company, "It is water the most disgusting which I have ever examined. When I first saw the water of the Southwark Company [before the merger], I thought it as bad as it could be, but this far exceeded it in the peculiarly repulsive character of living contents."

A reminder of the Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company which took its source from the polluted Thames

And this tangential link to a landmark legal case:

Students of law might be familiar with the no-longer-with-us Stepney Borough Council for its role in negligence and the duty of care. Paris v Stepney BC boils down to the fact the council didn't give a one-eyed man some safety goggles when they should have.

Stepney Borough Council was created in 1900 and abolished in 1965. Find this cover on Gunthorpe Street, E1

Related topics

- Published12 February 2021

- Published1 March 2016

- Published31 December 2014