Benin Bronzes: Horniman Museum to consider returning looted artefacts

- Published

There has been mounting political pressure for the return of objects

A London museum will consider returning artefacts obtained by "colonial violence" - including Benin Bronzes - to their countries of origin.

Collections at the Horniman Museum in Forest Hill include plaques, figures and ceremonial items taken from the Kingdom of Benin in 1897.

The decision follows a consultation with London's Nigerian community.

There has also been mounting political pressure for the return of objects taken in the 19th Century.

Since 2017, the Benin Dialogue Group, external, which brings together the current Oba (state leader of Edo), the Nigerian government and museums across Europe, has been working on a plan for some Benin Bronzes to return to Nigeria. If returned, Nigeria plans to house repatriated bronzes in the Edo Museum of West African Art set to open in 2025.

Campaign group Topple the Racists recently added the Horniman to an interactive map, external detailing the statues in the UK that have links to colonialism.

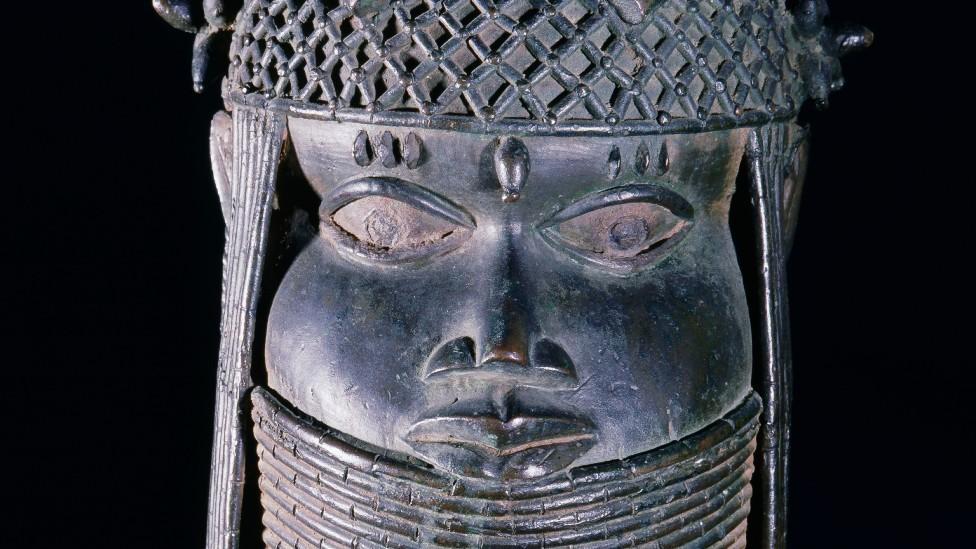

The Horniman's collection includes 15 Benin Bronze plaques depicting Obas (kings) and legendary figures, a brass cockerel called an Ebon which would be placed on the altar of a dead Lyoba (queen mother), and a ceremonial paddle called an Ovbevbe used by priests to ward off evil.

A brass bell, typical of those worn around the necks of Benin's warriors, is also in the collection, along with an ivory staff of office.

A plaque, an ivory staff of office and a brass bell, typical of those worn by Benin's warriors, are also in the collection

Chief executive of the museum, Nick Merriman, said its eponymous founder was a Quaker and a member of the Anti-Slavery Society.

"However, it is important to remember too that the wealth that enabled Frederick Horniman to make his collection, build his museum, and campaign as a social reformer, was reliant on the tea trade - a trade built on the exploitation of people living in the British Empire.

"We recognise that we are at the beginning of a journey to be more inclusive in our stories and our practices, and there is much more we need to do. This includes reviewing the future of collections that were taken by force or in unequal transactions."

The tea trade is known to have depended on the repurposing of land to create tea plantations, often forcing people living there to leave. The tea-growing process was hard work, poorly paid and, in many cases, used forced labour.

A carved ivory armlet is also housed at the museum

You may also be interested in:

The board of trustees said, external: "We recognise that the collections in the Horniman have been acquired at different times and under a range of circumstances, some of which would not be appropriate today, such as through force or other forms of duress.

"We understand that for some communities - whether in countries of origin or in the diaspora - the retention of some specific objects, natural specimens or human remains is experienced as an ongoing hurt or injustice.

"In recognition of this, the Horniman trustees wish to set out transparent policies and procedures by which communities can enter into discussion with them about the future of this material, including its possible return."

The Horniman's collection includes a brass cockerel - called an Ebon - which would be placed on the altar of a dead queen mother

Where is Benin City?

The Kingdom of Benin was a major city state in West Africa. It became part of the British Empire between 1897 and 1960 and is now within the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

Today the modern city of Benin (in Edo State) is the home of the current ruler of the Kingdom of Benin, His Royal Majesty Oba Ewuare II. Many of the rituals and ceremonies associated with the historic Kingdom of Benin continue to be performed today.

It is not to be confused with Benin, the modern-day nation-state.

Individuals or communities who wish to discuss the potential restitution or repatriation of cultural objects should contact the museum, which will consider whether the material was acquired illegally; through physical force; from people who were not the owners; or where the owner was compelled to sell or give them away.

It will also consider whether the nature of secret or sacred objects means displaying them is unethical.

Related topics

- Published14 March 2021

- Published12 September 2020