Pitt Rivers: The museum that's returning the dead

- Published

About 2,000 specimens at the Pitt Rivers Museum are of human remains

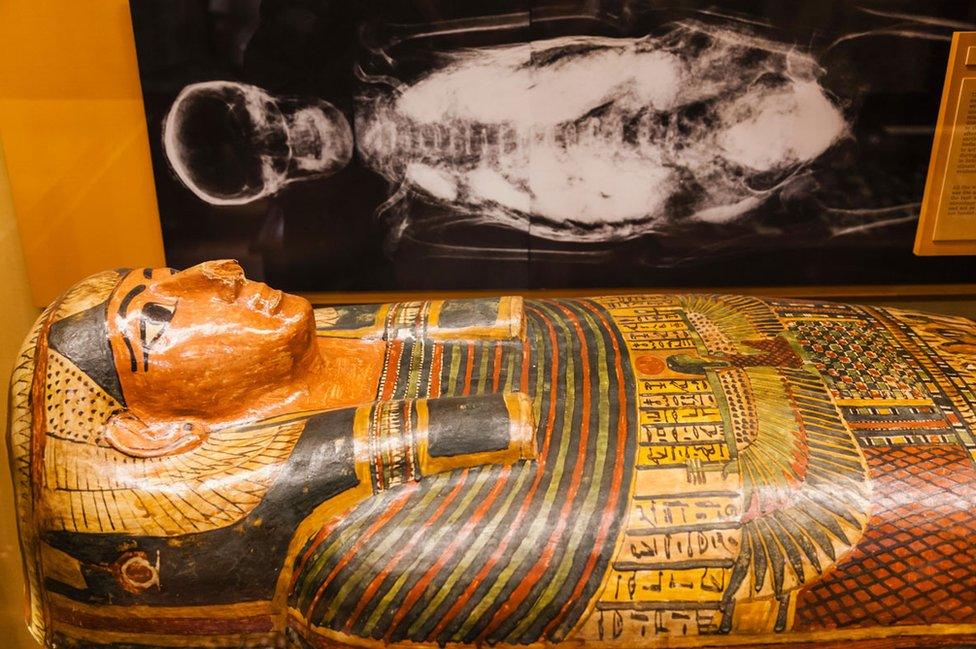

Treasures seized during Britain's colonial past are kept in museums across the country. But as times change, how do such institutions deal with the sensitive issue of the human remains in their collections?

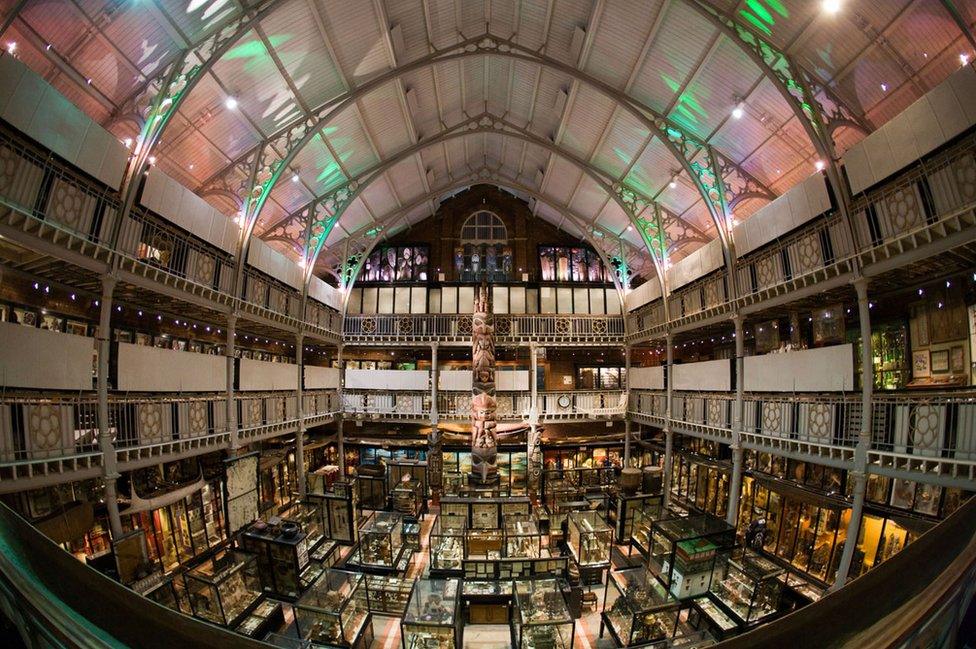

In Oxford, the Pitt Rivers Museum - founded with the collection of a Victorian general, Augustus Pitt Rivers - holds about 2,000 such specimens.

These body parts were brought back to Britain from across its empire, with little concern for the people from whom they'd been plundered.

The Pitt Rivers is one of several British institutions that are under pressure to re-evaluate the many colonial prizes in their collections.

"We can't undo history but we can be a part of the process of healing," says Laura van Broekhoven, director of the museum.

She says the process is about having an "open conversation" with those affected.

The museum was founded with the collection of Victorian general Augustus Pitt Rivers

Since the passing of the Human Tissues Act 2004, legislation that relaxed the rules regarding the moving of body parts, the Pitt Rivers has returned 22 such objects.

It's hardly a flood of returns to the former colonies, but it's a start.

The Pitt Rivers is currently negotiating the return of aboriginal human remains to Australia, and in May 2017 Maori remains were handed over to the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

In some cases these items first came to the UK because of adventurers who had connections to the University of Oxford.

"We've a lot of family connections between the university and the people of New Zealand that date back to the first contact between the Maori and British voyagers," Dr van Broekhoven explains.

"When the first British ships went to the area there were people from Oxford - wealthy naturalists who bought themselves a place on the ship that Captain Cook was navigating - and they brought objects here."

She says the Maori community showed "persistence and dedication" in getting them back.

Special ceremonies take place when remains are returned to New Zealand

Repatriations enable the "reconciliation of past wrongs and misdeeds"

Te Herekiekie Herewini, who works at Te Papa, has been described as the country's Indiana Jones of repatriations, external.

His mission is to return remains to their spiritual homeland "as a means of ensuring the ancestors may be comforted and embraced by their loved ones".

He says: "Maori and Moriori ancestral remains were taken without the permission of their family, and so the repatriation process allows for reconciliation of past wrongs and misdeeds associated with the arrival of Europeans into the South Pacific."

The museum has claimed back about 500 skeletal remains from various institutions since 2003, and the handover last year from Oxford included seven Toi moko, which are mummified, tattooed heads of Maori origin.

In May 2017 they were formally welcomed home by tribal representatives and government officials, and placed in a sacred repository, known as a Wahi Tapu.

They are only open to tribal representatives with a direct genealogical connection to them.

And what's happened to some of the Pitt Rivers' remains has been replicated elsewhere. The British Museum, which has more than 6,000 human remains in its collections, has repatriated at least 18 objects to Tasmania and New Zealand since 2004.

Human remains in the Pitt Rivers collection

2,000 individual objects

300 skulls, or parts of skulls

600 human bones, or artefacts incorporating them

700 specimens of human hair, or artefacts using it

Ashley Jackson, professor of Imperial and military history at King's College, believes if the situation was reversed, there would be strong feelings in the UK.

"If a museum in Beijing or Harare had the remains or funeral regalia of an important king or archbishop there'd be an enormous movement to try and get them back here," he says.

The current predicament is down to attitudes in the colonial period being extremely different, he says.

"Many people had an extraordinarily proprietorial view of the wider world, representing what many would've seen as a higher civilisation discovering, claiming, archiving, and bringing things back to Britain."

Maasai representatives from Tanzania and Kenya have visited the Pitt Rivers

They aided curators in making sure artefacts on display had the correct descriptions

He adds: "There must be an argument for a very human approach to understanding why certain communities, groups or national institutions want to have these back.

"They want to reclaim a history we had in many ways appropriated, and pronounced upon, and written about in a way that might not have reflected the truth."

But for Dr Tiffany Jenkins, author of Contesting Human Remains in Museum Collections: The Crisis of Cultural Authority, there now seems to be a "confusion in terms of what a museum's purpose is".

"Once it gets involved in community work, it's doing something slightly different, and I think in a way betraying its knowledge-seeking and educative purpose," she says.

"I'm uncomfortable when they abandon that because I think this has come out of a search for something new to do to make them relevant in the 21st Century.

"It moralises and apologises rather than investigates and opens it up... the beautiful thing about knowledge and understanding the past is that it should be open to everybody."

Origins of human remains at the Pitt Rivers

Asia - 500

Europe - 400

Oceania - 400

Africa - 300

North America - 150

Australia - 100

South America - 75

Other/unknown - 50

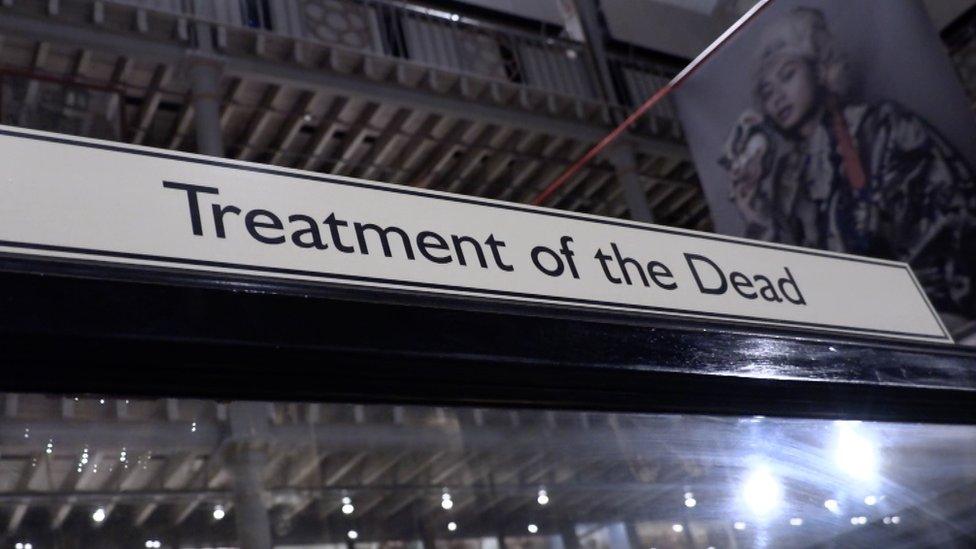

Among the Pitt Rivers' most popular exhibits are the "shrunken heads".

The 10 tsantsas were brought back from the Upper Amazon by British explorers in the late 19th Century, and now reside in a case called "Treatment of Dead Enemies".

To make a tsantsa the skin was removed, boiled and dried, the eyes and mouth closed with cotton string, the face blackened with dye, and the head strung on a cord.

These trophies were created by the tribesmen who took their enemies' heads to prove their courage and avenge a death.

We can't show a photograph of them because the museum considers them "sensitive materials" - to their descendants they are sacred objects.

At one point demand in the West was so high that tsantsas were made from people who had died of natural causes

But that doesn't necessarily mean they shouldn't be on display at the museum, explains Dr van Broekhoven. She says she has spoken to descendants of Amazonian tribespeople in previous projects, who had "no problem whatsoever" with such collections.

"They were actually very glad to see them on display," she says.

"They see that as a representation of their cultures and ambassadors for their cultures here.

"So in that sense I don't necessarily see the vaults opening and emptying as the only possible outcome of this process."

The museum's director says most of the museum's collections are uncontroversial

A link-up with another community took place in November, when Maasai representatives from Tanzania and Kenya visited the museum.

They worked with curators to make sure exhibits were correctly labelled and that they represented their culture fairly.

Dr van Broekhoven believes entering into the sprit of conversation with interested parties is important.

"I can't see how we would otherwise progress, especially as Oxford is a very international city," she says.

Despite its complicated past, Dr van Broekhoven insists the museum can still "speak about our common humanity".

"There's many different ways of knowing and being," she says.

"There's so much to learn from each other, and understand from each other."