The Ukrainian sisters separated by war

- Published

Mariia (left) and Tetyana Nesterchuk, two sisters separated by the war in Ukraine

Tetyana Nesterchuk left Ukraine in 1999 to study in England, becoming the first Ukrainian to win a place at Oxford University on a scholarship.

The London-based barrister's younger sister Mariia took a different path, staying in Ukraine to train as a doctor and later working for the country's authority responsible for drug approval.

They've had their arguments down the years, as all families do, but for Tetyana and Mariia Nesterchuk, the war in Ukraine has caused an unimaginable dispute: whether Mariia should stay or flee.

"I was on the phone to her every day crying, saying, 'please please', and she was crying saying, 'I can't leave Mum behind," said Tetyana, 39.

For the first 10 days of the war, Mariia, 36, was in Kyiv, staying in the family apartment alongside her nine-year-old daughter, their mother and brother.

Their mother refuses to leave as she's fled Russian aggression before, when the Russian-sponsored forces invaded Donetsk in Donbas in 2014. Eight years later, and she's not prepared to leave home again.

"She says she doesn't have the resources, the energy, to go. She said: 'I'm not leaving my home again, I'm never leaving my home'," said Tetyana.

Mariia and her mother decided to remain in Ukraine

"It was really difficult for me to accept that but at the end of the day, what I said to Mariia was Mum made her decision and we have to respect that.

"Deciding to become a refugee is not an easy choice. At an age when really you should be enjoying your retirement, running is just not something you want to do and so I've had to accept it.

"But I couldn't accept Mariia's decision as I said, 'you're responsible for your daughter'. I know she was torn between her child and our mum," she said.

At the time, Mariia told her that if they die, they'd all die together, however it was not a bomb that Tetyana was worried about, because if they died from a bomb, it would be "merciful".

"It's horrendous because I was thinking, 'what's the worst thing that could happen'? The worst thing isn't that they would die from a direct rocket hit, the worst thing is that they starve," she said.

The family were last all together in February - just days before the war began

It wasn't food Mariia was worried about though, but water.

Every day when there was a period of calm between the air raids, they would run out and buy anything they could eat that didn't need to be cooked. But water was not as easy to get hold of; bottled water had sold out since day one of the war.

The problem was that water from the taps gets switched off. The family would fill up every container they had but, Mariia explains, the constant worry was when it was coming back again and if they were going to have enough.

Not that they could go to their taps that often as the advice is to have at least two walls between you and the street - so they were living in the corridor of their apartment, with just mattresses placed on the floor.

Mariia eventually made the decision to leave Kyiv with her daughter, leaving her mother and brother there

In the end Mariia and her daughter left Kyiv, to rescue her ex-husband, his seven-year-old daughter, partner and dog from Irpin, an area just north of Kyiv which has come under ferocious bombardment from Russian forces.

"They made a dash for it, they weren't just walking, they were running, because overhead the planes were dropping rockets on people who were escaping," said Mariia.

"There were explosions on each side and they were running," said Tetyana. "It was more than 10km (six miles) before they were able to be picked up by my sister and her partner in a car. That was the last time they could escape Irpin because after that everyone who tried to leave was shot."

"It was like being in a film yet it wasn't a film. It was reality. They were running for their lives," added Mariia.

It took the two families - who were crammed into Mariia's small car - three days get to the village in western Ukraine where they're staying now. Not because of the distance, but because it was "one traffic jam across all of Ukraine".

While they were fleeing, Tetyana was at home in London, worried and anxious.

She busied herself trying to find somewhere for them to stay but in the end, they managed to find a place themselves with friends who opened their home to them.

"I think my family have protected me from a lot," Tetyana said.

"Every time I call them they have been positive and saying how everything is great, you know everything is fine, so as not to worry me, but I feel helpless. No matter what I do it isn't enough."

Being thousands of miles away has been tough.

"The worst thing is realising that my nation is being murdered for no reason, that we are a news story.

"Even though they know I'm personally affected, a lot of my acquaintances sort of talk about it to me like they would about any other news story and that actually really hurts because they try to put forward different arguments for and against Nato getting involved but actually for me this is so emotional I can't get involved in the politics," she said.

"For me, the answer is pretty clear: you do not kill women and children. He has bombed a maternity hospital in Mariupol. As a woman who has given birth I cannot imagine what that must have been like."

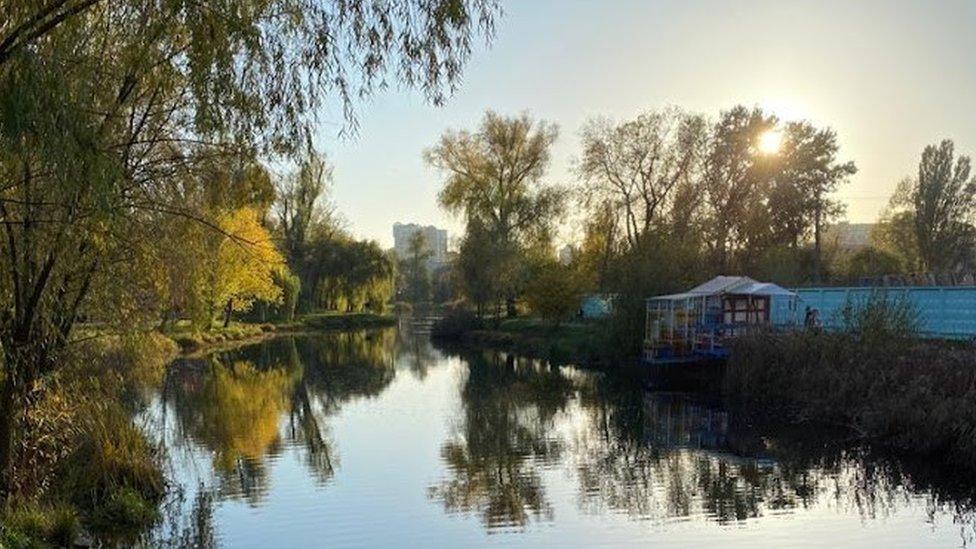

The sisters both hope to return to their favourite park - Park Peremohy - known as Park of Victory

Although it is incredibly difficult to see the damage being done to Ukraine now, Tetyana cannot impose a news blackout on herself because she is volunteering with Ukrainian Freedom Fund, a humanitarian charity that was established following Russia's invasion of Tetyana's native Donbas and that is now reactivated. It is trying to get medicine, food and other resources to those in need.

Mariia is helping too - in Ukraine - with the local volunteer organisation.

They receive messages via social media and Telegram channels which they check out before sourcing the aid and sending it to the border.

Mariia then helps to organise transportation in Ukraine.

It's provided them both with a useful distraction, a way of coping.

"The anger and fear has meant I'm able to do a lot more than what I may have been able to have done in peacetime," Mariia said.

"At the moment it is a coping mechanism but I'm worried that I'll have a breakdown later on," she said.

"I am too," replied Tetyana.

"I understand people who flee, but I have deep respect for Mariia's decision because we need people in Ukraine helping. We can't all just abandon our land," said Tetyana.

The family all have visas so could come to live with her in London, but - for now - they want to stay in Ukraine.

"I will only leave Ukraine in desperate circumstances," said Mariia. "While I can still be helpful, I will stay."

Tetyana and her children hosted Mariia and her daughter at Christmas

The last time they were all together was 12 February, when Tetyana and her young children travelled over to Ukraine to celebrate her mother's 60th birthday.

"It was so recent but it feels like it happened in some sort of parallel reality," said Mariia.

"It does feel like it happened in another life, in another country," agreed Tetyana.

For now, aside from volunteering and her job working for Ukraine's drug approval agency - which at the moment she continues to do from where she's now living - Mariia is focusing on home schooling her daughter, just like she did during the pandemic. The only difference is there are no teachers to provide guidance.

If she could, she would return to Kyiv.

Currently trains are still operating, but it is impossible to drive into the city. Once you've left, you've left.

"I constantly feel like I want to go back; that feeling doesn't stop," Mariia said.

For now, they're content that they're all still able to contact each other, mainly on the family's WhatsApp chat.

Calls are made twice a day, in the morning and evening.

"I wanted to speak to them all the time," said Tetyana.

"When they were all in Kyiv I would wake up in the morning very early and want to call them straight away but I knew they'd be asleep because they couldn't sleep at night due to the air raids so I'd have to make myself wait until I felt like I could call them.

"So that was the worst time, in the mornings.

"Every time I speak to them I think this may be the last time so I definitely don't want to say anything that I'd regret and in that sense I guess you can say we're lucky because sometimes you don't get to.

"With my dad, he died very suddenly, I didn't know the last time I spoke to him would be the last time.

"At the moment I treat every time as possibly the last time, so I make sure I say the important things. It made me realise that all the stuff, our material belongings, is not important and in a way I would give it all up for the opportunity to be in Kyiv with my family."

"In peaceful Kyiv," said Mariia.

"Hopefully there'll be a peaceful Kyiv soon," replied Tetyana.