Will Low Traffic Neighbourhoods drive London's elections?

- Published

Low-Traffic Neighbourhoods feature planters aimed at stopping traffic on residential roads

It is difficult to remember a transport scheme attracting such support or such vitriol - will Low-Traffic Neighbourhoods drive this year's local election in London?

It was a newly pedestrianised street that proved the clincher.

Five years ago Lucie Beeston opened her gift shop in Francis Road in Leyton, east London, only after the council finished the roadworks.

"Before, this was a really smoggy and polluted road," she says.

"Now it's great. We love it. It's become a proper hub for the community."

Her local council Waltham Forest was ahead of the game.

Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTNs) would spring up all over London at the start of the coronavirus pandemic.

Lucie Beeston (l) supports the pedestrianisation of the road outside her shop in Leyton

Waltham Forest has been working on pedestrian and cyclist-focused schemes for several years to create London's first so-called "mini-Holland".

It was a battle. Some drivers whose journeys were made longer by the pedestrianised roads were not impressed.

But nowadays, Lucie insists, you don't hear complaints.

"It's made a remarkable difference," she says.

Over the past couple of years, many London councils have been grappling with the challenge of creating pedestrian-friendly LTNs, knowing that if they got it wrong in the view of their residents and businesses they could pay a heavy price with voters.

LTNs use planters to stop traffic going down residential roads. The aim is to make getting around by car a lot more difficult, driving down car ownership and getting people to switch to cycling and walking.

In the past two years, 97 LTNs have sprung up across the capital - out of the 160 LTNs proposed by local councils.

In a sign of how sensitive the issue of LTNs has become, the data shows 27 schemes have been cancelled and 39 paused or suspended.

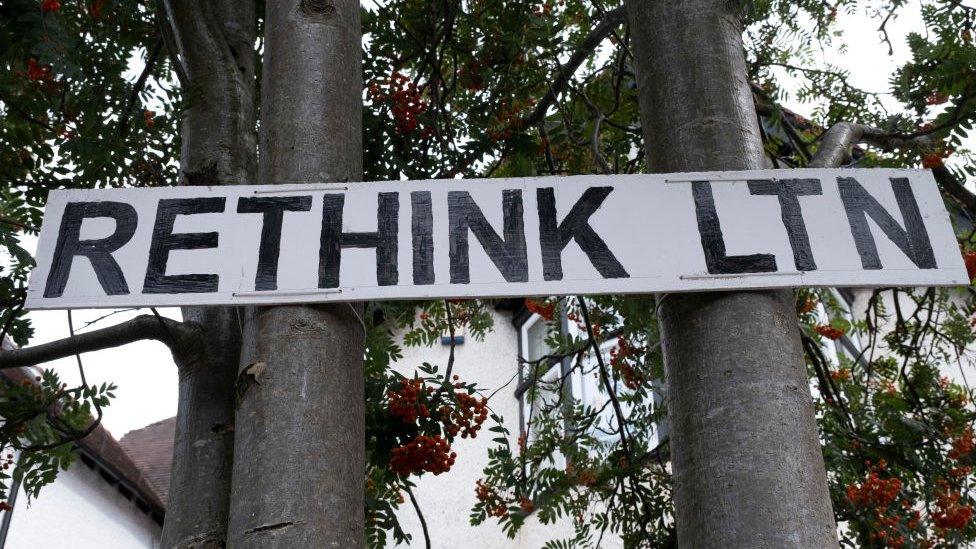

LTNs have attracted protest from local residents across London.

So could LTNs have a bearing on the London borough elections?

Nick Bowes, chief executive of the Centre for London think tank, believes it's possible.

"Battles about this predominantly pitch Conservatives against a pro-coalition of Labour, Greens and sometimes Lib Dems," Mr Bowes said.

"Very localised surprises might happen."

The pedestrianisation scheme in Waltham Forest is held up as an exemplar of how to make sure a local community is involved in the decision-making.

But in many other areas, it's been heavy-going.

Political will

In the spring of 2020, the flood of LTNs was seen by the government as seizing an opportunity from the crisis that was Covid-19.

It was a chance to take advantage of unprecedented restrictions imposed on people's freedoms and movements to encourage a big leap in attitudes on car use and street space.

But in many places in London the imperative to shift behaviour to tackle climate change rubbed up against fears of voter retaliation.

Opposition to LTNs is "short-termist" according to Simon Munk from the London Cycling Campaign (LCC).

A four-year election cycle can restrict measures with long-term advantages.

But Mr Munk says it's only a "lack of political will" preventing LTNs having more of an impact.

Supporters of LTNs make their voice known

But even in places where the thinking behind LTNs landed well from the start, some councils are proceeding with caution.

Labour-controlled Lambeth trialled five schemes during the pandemic.

Currently, the council only plans to make two permanent, with the other three under review.

Other councils took more drastic steps - undoubtedly with an eye to the local elections.

Conservative-run Wandsworth Council initially welcomed the Conservative government's traffic-calming neighbourhoods.

"These are designed to make residential streets much more pedestrian and cycle-friendly whilst deterring cut-through traffic," the press release read, external at the launch of the trial.

"The changes…. need to free up additional space on our highways in support of social distancing, as well as encouraging alternative forms of travel."

Several councils have changed their approach to LTNs

But the commitment didn't last long.

A few weeks later, a spokesman explained LTNs weren't a good idea after all.

The council now said: "We have monitored the traffic flows and listened to feedback from residents and businesses. We have also spoken to our partners including local hospitals and key services to hear the impact on them.

"It is clear that the LTNs are not delivering the benefits we want to see."

It was in the borough of Ealing in west London where residents mobilised against LTNs with the most successful and obstructive effect.

Uproar over LTNs forced the Labour administration to junk seven out of nine schemes - with the approaching election very much in mind.

The LTN effect

According to the monitoring data, LTNs had not caused significant extra displaced traffic or congestion. Neither was air quality worse - though it was not shown to be much better, either.

But no evidence was collected on a shift to more walking and cycling.

It also proved hard to show the difference in vehicle use made by the LTNs, as councils didn't have time to capture the picture pre-LTN.

New Covid lockdowns' rapid introduction skewed the picture.

One big problem arose from how quickly councils were expected to install the planters and the cameras to qualify for government funding.

In Ealing, public consultation was to come after, not before, LTNs were implemented - clearly unnerving some residents.

Poor communication and engagement with local communities failed to halt the momentum behind objections.

Independent consultants brought in by the council found Ealing "lost control of the narrative about the need for and purpose of LTNs".

Nevertheless it seems likely that in Ealing, as elsewhere, LTNs will be revisited and the arguments better made - as a spokesman indicated last autumn.

"We will continue to explore future LTN schemes, but we will only be implementing where we are satisfied that the data and public support them."

Reticence over LTNs led to Ealing and six other London councils - Harrow, Hillingdon, Kensington & Chelsea, Redbridge, Sutton and Wandsworth - having their funding for active travel schemes suspended by the government.

Simon Munk believes a "small minority dominate the airwaves" in opposition to LTNs

But Mr Munk from the LCC says all councils will have to grasp the nettle in the end if climate targets are to be met.

"We know it can be scary and the local opposition can be terrifyingly loud," he said.

"But this is not the local electorate. It's just a small minority dominating the airwaves and making noise.

"When the noise blows over we've still got to deal with climate change."

Nearly two decades ago, Ken Livingstone staked his mayoralty and political life on introducing the congestion charge.

He dared and won but in many areas of London there are local leaders who may feel they can't take the risk.

- Published25 April 2022

- Published31 March 2021

- Published28 March 2022

- Published28 March 2022