Edith Thompson: U-turn over rejection of hanged woman’s pardon

- Published

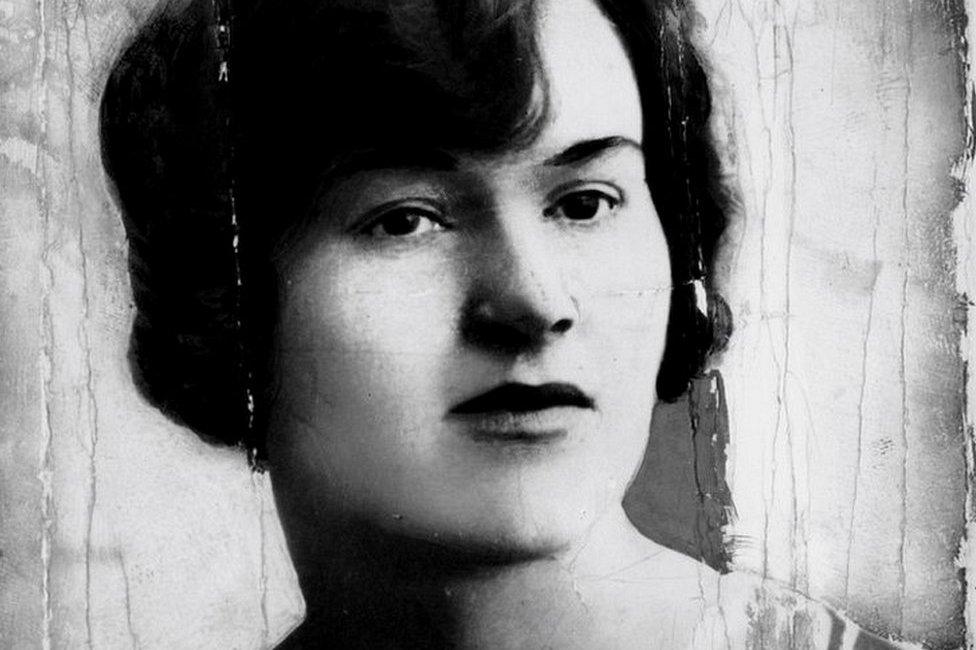

Edith Thompson was hanged at Holloway Prison on 9 January 1923

An application to pardon a woman who was hanged 100 years ago for the murder of her husband is being reconsidered after a government U-turn.

Edith Thompson, 29, was found guilty of murdering Percy Thompson, despite there being little evidence against her and the insistence of the killer - her lover - that she was no part of it.

A request made last year was rejected by Justice Secretary Dominic Raab.

The pardon is now being looked at again after errors were pointed out.

Percy was stabbed in Ilford, east London, on 3 October 1922 by 20-year-old Frederick Bywaters. The Thompsons had been making their way home from the theatre.

The case caused a huge sensation as letters written by Edith uncovered during the police investigation revealed an affair between her and the killer.

She was executed at Holloway Prison on 9 January 1923 where she had to be carried to the gallows with her arms and ankles bound following days of injections of a powerful sedative.

The application for a posthumous pardon under the Royal Prerogative of Mercy was made by a City firm of solicitors in July last year on behalf of Prof René Weis, who was previously made Edith's heir and executor by her family.

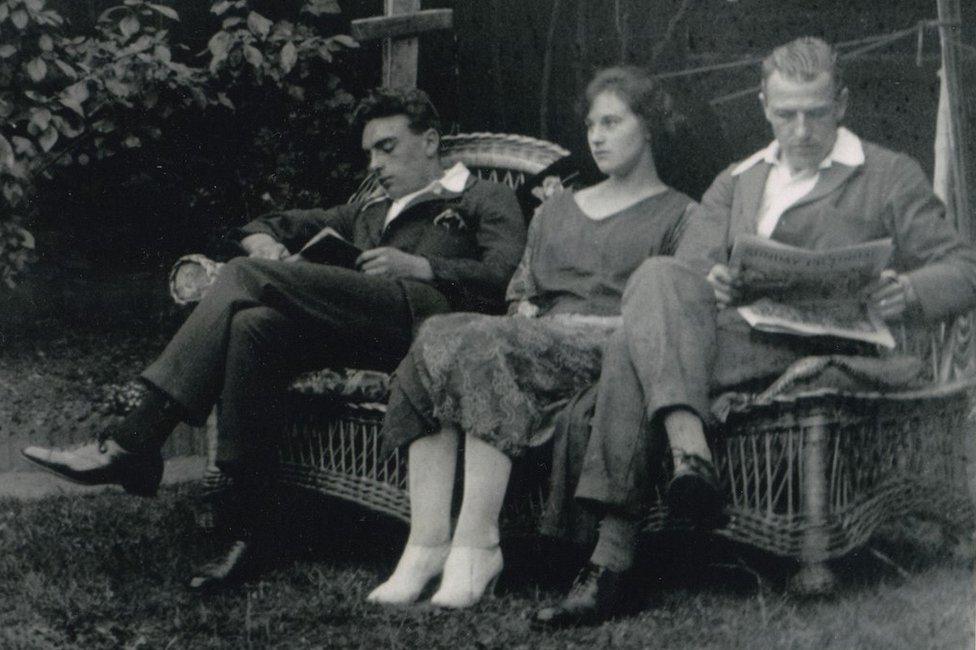

Freddy Bywaters (left), the lover of Edith Thompson, pictured with her and her husband Percy Thompson in the married couple's garden in east London

In the letter to the justice secretary, the application states that both Edith's trial and subsequent appeal were "grossly unfair" and she had faced a judge who was prejudiced against her from the start.

One issue highlighted was that the judge, Sir Montague Shearman, allowed Edith's love letters to be used as "evidence of intention and motive" even though they had no connection to the murder, with no mention of a stabbing or the setting up of an attack included in them.

The application argues their inclusion affected the fairness of the trial, with sections presented out of context by both the prosecution and judge to suggest Thompson helped plan the killing; this included falsely claiming that a meeting the accused pair had in a tea room was when they discussed the murder.

It also notes the post-mortem examination on Percy found no signs of poison or glass in his body, which were the only methods of killing vaguely hinted at in Edith's letters, which were argued to be just fantasy.

However, the prosecution falsely told the jury there were "practically" no traces of any poisoning, in what is claimed was an effort to mislead them.

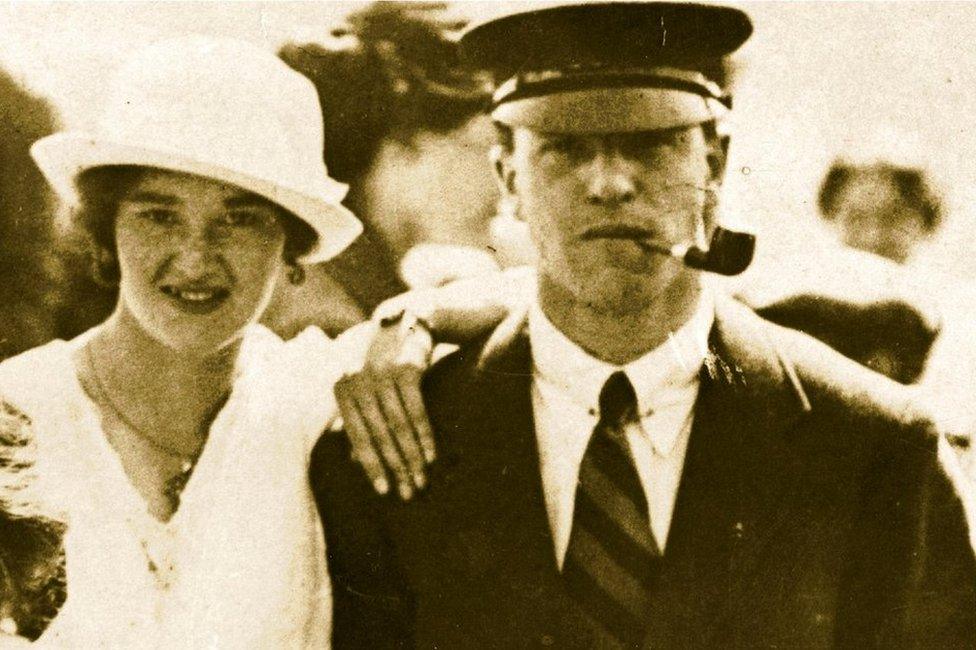

Edith Thompson (right) and her younger sister Avis Graydon were both born in the 1890s at the end of the Victorian era

Mr Justice Shearman is criticised for his actions throughout the trial, including in his summing up, in which he was accused of trying to manipulate the jury into following his condemnation of the two lovers.

Speaking about the affair, he told the jury, "I am certain that you, like any other right-minded persons will be filled with disgust at such a notion", while he also inaccurately questioned the reliability of a witness who had told the court he heard Edith shout "oh, don't, oh don't" on the night of the killing.

The controversy over Edith Thompson's love letters

Edith and Percy Thompson were married in January 1916

As the only evidence submitted against Edith Thompson, the 26 love letters she wrote to Freddy Bywaters used during the trial were key to the case.

In his summing up, Mr Justice Shearman told the jury the "necessary absence of evidence" in the case made the consideration of them "of so much importance".

An interview given by one jury member 30 years after the trial revealed they took this to heart, telling a newspaper the term "nauseous" was "hardly strong enough to describe their contents".

"The jury performed a painful duty, but Mrs Thompson's letters were her own condemnation," they added.

However, modern analysis of the notes has shone a different light upon them.

Criminal psychologist Dr Donna Youngs studied them for the BBC One programme Murder, Mystery and My Family in 2018 and found they showed Edith's thinking was almost "childlike", adding that there was "nothing... which is consistent with a genuine commitment to killing her husband".

In a relatively short response sent on 19 October 2022, seen by the BBC, the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) said the justice secretary could not recommend a pardon because no new evidence about the case had been provided, as was required for a Royal Prerogative of Mercy.

It added that Prof Weis would not be able to appeal against the decision but he had also not yet approached the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC), which had the power to refer cases for appeal.

Nevertheless, Prof Weis's solicitors replied the following month saying they were "extremely concerned" by the reasons given to turn down the application, which they believed demonstrated a misunderstanding of the law about pardons.

They pointed to the cases of Derek Bentley, who was hanged for the murder of a policeman in 1953 but had his conviction quashed in 1998, and codebreaker Alan Turing, who was given a posthumous pardon in 2013 over his conviction for gross indecency, when no new evidence was provided for either.

They also explained Prof Weis did not have the statutory right to approach the CCRC as that could only be done by the MoJ.

Prof Weis led a service at Edith Thompson's grave, where she is buried alongside her parents, in City of London Cemetery on Monday to mark the centenary of her death

A few days before Christmas, the solicitors served notice on the MoJ of their decision to proceed to a judicial review over the rejection and received a note the following day that said the government department would now reconsider the pardon and that the process had started again.

Speaking about the government's initial response, Prof Weis said he "found it deeply shocking that on a matter of such moral importance, the violent death a young woman... the MoJ, in all our names, should see fit to reply with a copy-and-paste Civil Service template".

"If we believe in a just law, then we must also believe that past mistakes, miscarriages of justice as patent and as crassly gendered as this one, can be set right," he added.

"Nothing can restore her stolen life to Edith Thompson but pardoning her for something she did not do must be right."

The MoJ has been approached for comment.

The trial was a public sensation and queues to get into the Old Bailey would build up from the early hours each day

Follow BBC London on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hellobbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published9 January 2023

- Published9 November 2015