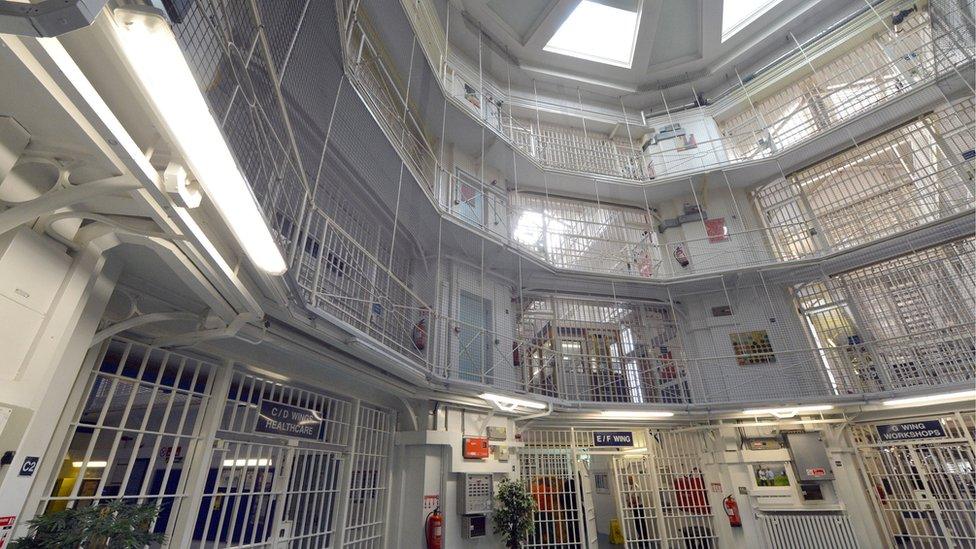

Pentonville Prison: Ex-inmate explains impact of overcrowding

- Published

Femi Laryea-Adekimi says Pentonville is run down and infested with rodents

The population of HMP Pentonville is rapidly increasing. The current head count at the Victorian-era jail in north London is around 1,185 and is soon expected to reach 1,205 - about 200 up on a year ago. Former inmate Femi Laryea-Adekimi has told the BBC how prisoners share their dilapidated cells with rats and cockroaches, and are often locked up for as much as 23 hours a day.

"The noise of shouting and wailing is the first thing that hits you when they open the door on to the wings, and it never stops through the night," says Mr Laryea-Adekimi, who was sentenced to 20 months for fraud and was released in 2020.

"You hear people screaming out and smashing up their cells, just desperate for some kind of attention. I could see their mental state deteriorating so quickly from being locked up 23 hours a day."

Pentonville was built between 1840 and 1842 with a capacity for 520 inmates.

Conditions at Pentonville have been described as "inhumane" by the chair of its monitoring board

In the most recent annual report of the prison, Pentonville was described as "struggling with overcrowding and in poor physical condition". A recent survey by the Inspectorate of Prisons also found that 69% of Pentonville inmates said they spent less than two hours a day outside their cells.

Mr Laryea-Adekimi, 38, describes the Victorian-era cells as "dilapidated, tiny, the size of a bathroom, and who you share this with is luck of the draw".

"It doesn't how matter how much you clean the cell, the cockroaches don't ever go away; the ground-floor wing has rats and mice."

Conditions are "inhumane" and "not conducive to any kind of rehabilitation," according to the chair of Pentonville's monitoring board, Alice Gotto.

Prisons minister Damian Hinds said increasing the prison population was going to be "necessary for the foreseeable future" and justified Pentonville's increase by referencing its 2012 capacity of 1,310.

But in a letter to the minister, Ms Gotto pointed out that capacity was reduced by 40 in 2016 after two prisoners escaped and one was murdered. She said that regardless of population, staffing levels were "consistently too low for the prison to be able to run a full regime".

At Pentonville, 69% of inmates said they were let out of their cells for less than two hours a day

"The idea that you could fit an extra 300 into Pentonville is totally insane," says Mr Laryea-Adekimi, who works at the Prison Reform Trust.

"There are no empty cells. The first immediate and catastrophic consequence of this is that they bunk up more low-risk prisoners with high risk. This means someone who is on remand, not yet even convicted of any crime, or someone convicted of something low level, is locked up for 23 hours a day with someone who is very dangerous with violent tendencies or who has severe mental health problems.

"As you an imagine, this will likely result in more violence, deaths, worse mental health and self-harming. All the system is doing is damaging them even more and throwing them back out.

"The impact of this doesn't ever seem to be thought about; we're not human, or part of society. If you did this to any other cohort there would absolute outrage but because they are prisoners, it's expected.

"When inmates hugely outnumber staff, it's just a matter of time before they catch wind of this and it can lead to riots."

Mr Laryea-Adekimi said there were no empty cells at Pentonville

The number of prisoners in custody awaiting trial in England and Wales is at a record level - in late 2022 it was the highest for at least 50 years.

High remand numbers mean prison mobility stagnates. According to Ms Gotto, with the prisoners who have not been on trial and officially sentenced, their behaviour cannot be assessed and they cannot be categorised and progress to open prisons. Pentonville is more than 75% remand at the moment, similar to other local prisons where detainees are taken immediately from the court.

Even for the those not on remand, the staff shortages often mean that they do not spend enough time outside their cell to progress.

Prison numbers

The retention of prison officers is a pressing issue

England and Wales has the highest imprisonment rate in Europe with 136 jailed per 100,000 people

In the past 12 months the inmate population in England and Wales has increased by 2,700 to 85,000 - the UK total is expected to hit 100,000 by 2026

There are 14,000 remand prisoners in England and Wales, an 11% rise in the same timeframe

Sentences of 10 years and longer have risen 60% - from 1,117 given in 2012 to 1,789 in 2022

Sentences of five years or less have dropped 39% - from 95,984 in 2012 to 58,093 in 2022

There are about 3,000 fewer prison officers in England and Wales than there were 13 years ago

Half of prison officers who left the service in England and Wales last year had been in the role for less than three years - more than a quarter left after less than a year

Source: ONS/Ministry of Justice

"So many young men are on remand, not even guilty, some waiting years for their trial and now you want to lock them up with really dangerous men, some convicted of horrific crimes. If they're trying to break people, break their spirit and their mind, they're doing the right thing," Mr Laryea-Adekimi says.

"The prison staff shortages are also critical at the moment - you can't treat prisoners humanely and rehabilitate them if you have no-one to ever unlock them out their cell. "

The record level of new remand prisoners is largely due to court backlogs from the pandemic as well as barrister strikes, a Justice Committee inquiry recently found.

Pentonville Prison was not designed to house the number of inmates it does

The principal pressure on the prison population in the long term is the increasing length of sentences, the director of the Prison Reform Trust, Peter Dawson, told the BBC.

The average length of sentences for courts in England and Wales has risen 50% in a decade, from a year and two months in 2012 to a year and a eight months in 2022, data from the Ministry of Justice shows.

For more serious offences, the average prison sentence is now just over five years - more than two years longer than in 2008.

According to Mr Dawson, the "dramatic inflation in the length of prison sentences is the prime reason our prison population hasn't fallen over the last decade, and why it is set to increase to record levels".

"What's more, sentence inflation has been a deliberate political choice - an easy way to look tough on offending, even though there is no evidence that longer sentences make any difference to crime rates.

Your device may not support this visualisation

"If we want a prison system that works, and that no longer relies on using historic anachronisms like HMP Pentonville, we have to end our love affair with imprisonment.

"That must start with a fundamental look at how harshly we punish, and what we expect to achieve in doing so."

A Prison Service spokesperson said: "Major refurbishment works at HMP Pentonville means the prison can carefully increase its operational capacity and limits are based on the number of prisoners who can be safely held there.

"We are also hiring more staff and boosting additional capacity across the prison estate to ease pressure, including rolling out hundreds of rapid deployment cells opening in the coming months."

The spokesperson added that conditions had improved since the last inspection and £4bn was being invested to create 20,000 more prison places, by building six new prisons and delivering major expansions.

Follow BBC London on Facebook, external, Twitter , externaland Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hellobbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published10 March 2023

- Published6 February 2023

- Published8 March 2023