Croydon tram crash - the unanswered questions

- Published

Tram 2551 was en route from New Addington to Wimbledon via East Croydon when it crashed

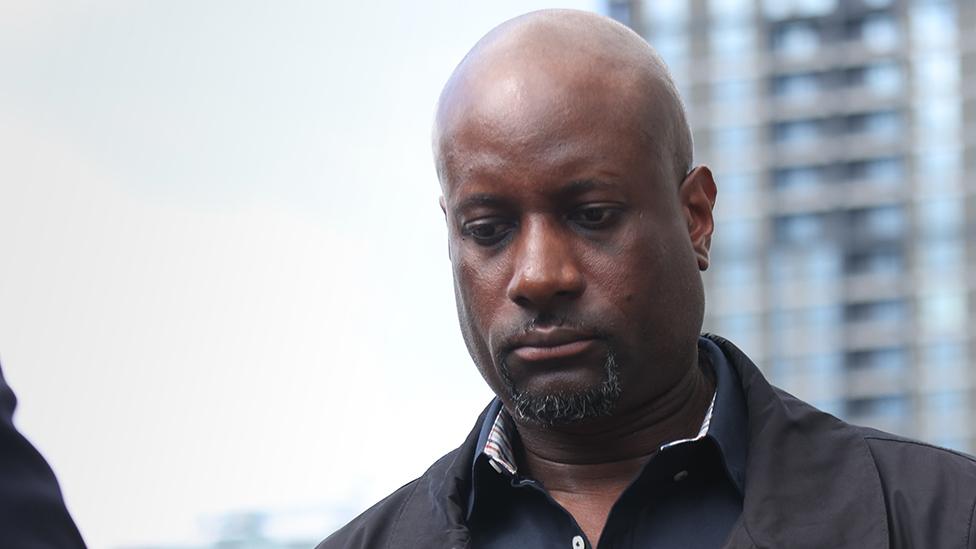

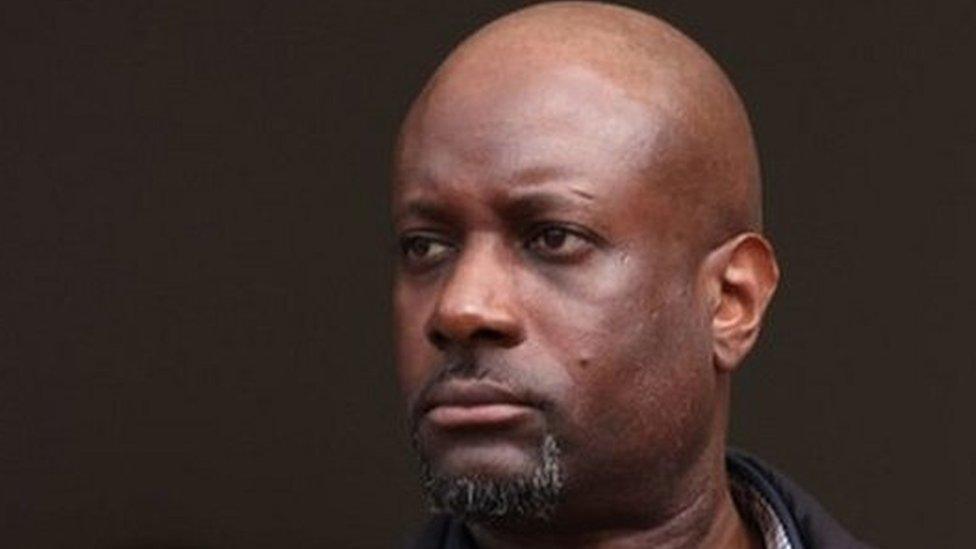

The man at the controls during Croydon's fatal tram crash cut a lonely figure in the dock at the Old Bailey.

Alfred Dorris faced cross-examination for two days over the disaster, which killed seven people and injured many others.

He was one of the better drivers on the south London tram system, the court was told.

He was diligent at work and his main concern while driving was about the "comfort of the passenger".

So, what happened? Why, while at the controls of Tram 2551, did it reach a speed of 70 km/h into the sharpest corner of the tram network?

What happened on that dark, ugly morning was pored over during this trial.

Under health and safety laws, he was charged with not taking "reasonable care" of his passengers in a case brought by the regulator, the Office of Rail and Road.

A jury has found him not guilty of that charge.

The tram Alfred Dorris was driving was moving at three times the correct speed

Sixty-nine passengers were on board when the tram derailed. All bar one were affected.

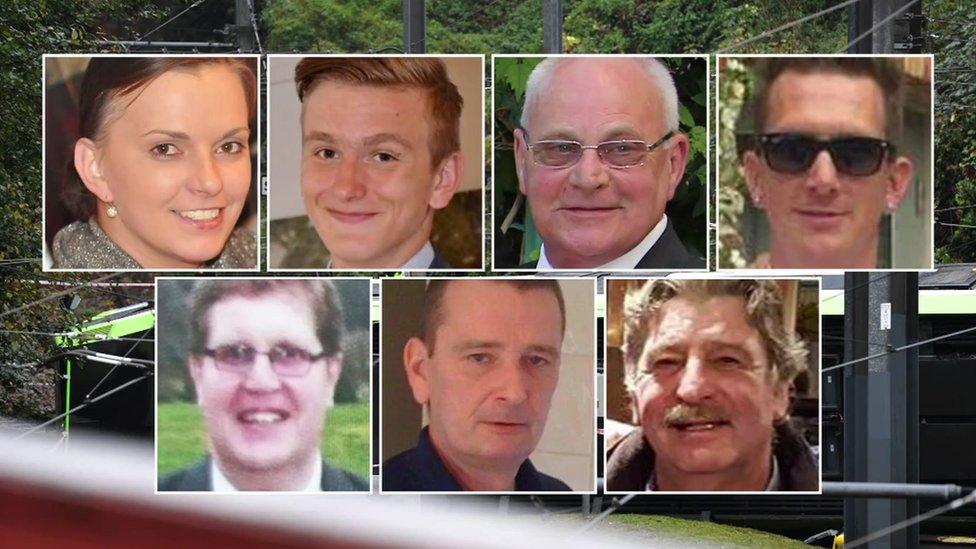

The seven people who died were Dane Chinnery, Donald Collett, Robert Huxley, Philip Logan, Dorota Rynkiewicz, Philip Seary and Mark Smith.

Another 61 passengers were injured, of those 19 were seriously hurt. Many sustained life-changing injuries, from chronic pain to amputations.

The trial

Passengers told the court that when the tram overturned, they were "flung around" as if in a washing machine or a ball in a pinball game.

When some passengers came round, they reached the driver using the lights from their phones.

With the tram on its side, Mr Dorris initially told passengers straight after the crash: "I saw something in front of the tram." But then he also said: "I must have blacked out," the jury was told.

Matthew Parnell, who was on the tram when it overturned, told me he was sitting reading his magazine at the time and it was dark and raining outside.

"All I remember is thinking he was going a bit quick through the tunnel and thinking no more of it and carrying on reading my magazine and then I woke up in St George's Hospital in Tooting about four hours later wondering why I'm here."

The past six years have been hard, he said.

"I was an HGV driver, and they took my licence away because of my head injuries.

"I've got it back now but it's been a bit of a struggle, but we have got there. Life goes on, you have to just carry on the best you can," he said.

"Seven people lost their lives, which is very sad, and other people lost their limbs and things like that so in the way I've come out, physically unscathed, is a godsend."

In court, Mr Dorris said on several occasions he did not fall asleep while driving the tram. He said he was confused and disorientated.

He told the jury he thought he was going in the opposite direction on a stretch with no curve.

Dorota Rynkiewicz, Dane Chinnery, Donald Collett, Mark Smith, Phil Seary, Philip Logan and Robert Huxley were killed in the derailment

Mr Dorris became emotional a number of times, telling the victims' families: "I'm deeply sorry I was not able to do anything to reorientate myself and stop the tram from turning over."

He described how he had suffered post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after the crash. He said he was "broken". The court was told he had separated from his wife since the crash and was no longer in contact with her, or his daughter.

He seemed resigned to whatever fate justice was going to throw at him. When asked if he had taken reasonable care of his passengers, he said: "I turned up as a professional driver as I always do. It just went horribly wrong for me.

"It's not for me to say if I did or I didn't."

The defence was he didn't fall asleep but was disorientated, and a major contributor to that was environmental factors outside his control in the Sandilands tunnel including a lack of visual cues, poor speed limit signage and a lack of lighting.

The court was shown videos that highlighted the lack of lighting in the tunnel. Many of the lights were broken, water had affected the electrics. One witness who worked at the operator Tram Operations Ltd (TOL) admitted they had not been maintained to the required levels.

The unanswered questions

Throughout the hearings, families of some of the victims sat through the evidence with a quiet, stoic dignity.

They have waited six years to get to this point. But there are still many questions they have not had answers to.

The court heard how Transport for London (TfL) and TOL, had allowed a safety blind spot to develop. No risk assessment was ever carried out on a possible high-speed derailment on this sharp corner into Sandilands in Croydon.

Measures to control the risk of derailments were not in place, the court was told. The prosecution said the operator had created "an accident waiting to happen".

Both TfL and the operator have pleaded guilty to not taking reasonable care under health and safety laws. They will be sentenced at a later date.

The cases against them were also brought by the Office of Rail and Road.

And while TfL and TOL were culpable, the prosecution also said it was Mr Dorris who drove the tram at speed into the corner and he failed to take care of his passengers.

But the jury disagreed and so many questions remain.

Why were safeguards not in place? Why were previous incidents - including a near-miss on the same curve just 10 days prior to the crash - not followed up on?

And did the tram company and TfL deal with fatigue management effectively?

Did a culture of blame exist?

During the inquest into the deaths of those killed in the crash, the apparent issue of fatigue on the job came to light.

The hearing was told three-quarters of drivers with the operator who had taken part in an anonymous survey in 2017 believed the firm's fatigue management was "poor", or "very poor".

The same survey revealed drivers were also scared to self-report near-misses. Why?

Because, the survey found, they believed they would be disciplined.

The inquest heard five drivers with the same operator in the previous five years had been disciplined and/or sacked for falling asleep while driving.

Did a culture of blame exist at the firm?

At the time of the crash, Michael Liebreich was on TfL's board and was head of its safety panel.

He told me many of these issues were systemic and structural at both TOL and TfL.

An initial report by the Rail Accident Investigation Branch (RAIB) found fatigue was "not a factor" in the crash. But Mr Liebreich believes that was flawed and there was a long series of fatigue issues at the operator.

An audit in 2014 highlighted fatigue management as a concern but the operator was given a clean bill of health.

Also, Mr Liebreich thinks the RAIB should have looked at a safety audit that was going on at the time of the crash and eventually cancelled by TfL.

The prosecution described the situation as "an accident waiting to happen"

As part of a BBC investigation after the crash, journalists spoke to four drivers on the same network who admitted they had fallen asleep at the controls.

The RAIB said it recommended TOL should "improve its management of fatigue risk and encourage an organisational culture in which tram drivers feel able and willing to report safety incidents".

'Could have happened to any driver'

Mr Liebreich believes many of these issues should been properly scrutinised.

"This was culture," he said. "This was an accident that could have happened to any of the drivers on the Croydon Tram at the time.

"There's a wealth of information that's emerged since that shows long-standing issues around, particularly, fatigue but also working conditions… I think the fatigue is at the core.

"On top of that, there were cultural issues around reporting around drivers worried about being disciplined for reporting that they felt tired."

He added he thought there was a "wealth of management problems that led up to this, such a tragic, tragic accident."

TOL told BBC London it had introduced new measures as recommended by the various investigations, such as a review of roster planning and renewed guidance to increase fatigue awareness among drivers. It said it had also worked with TfL to install in-cab monitoring devices, which alert the driver if there is any sign of fatigue.

TfL said it had made "robust and lasting safety improvements since 2016". The RAIB has been approached for comment.

There have indeed been changes to the tram network since the crash.

There are also better signs, more speed restrictions, an automated braking system and speed monitoring. The CCTV has also been updated.

There has been a feeling that this is a forgotten tragedy.

It was overshadowed on the day by news coverage of the arrival of Donald Trump in the White House.

It has taken a long time to get this far.

The families have previously appealed, in vain, for a public inquiry.

And six years on, there still remain many unanswered questions.

Follow BBC London on Facebook, external, Twitter , externaland Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hellobbclondon@bbc.co.uk

- Published19 June 2023

- Published9 June 2023

- Published8 June 2023

- Published17 May 2023

- Published4 August 2021

- Published22 July 2021

- Published24 April 2017