Windrush Day: Who were the passengers heading to London?

- Published

RAF officials from the Colonial Office welcomed passengers when they disembarked from the MV Empire Windrush

Seventy-five years ago, 1,027 passengers disembarked from the MV Empire Windrush at Tilbury Docks, with about 500 of those being migrants from the Caribbean who had travelled to fill labour shortages in the UK.

Those who arrived would have had to fill out a landing card stating various details such as their age, previous residence, occupation and their proposed address for where they were going in Britain.

These documents were destroyed by the UK Home Office in 2010 leading to the Windrush scandal where many of those who had migrated to Britain became unable to prove they were legally allowed in the country.

In response to this Dr John Price, a senior lecturer at Goldsmiths, University of London, and his colleagues transcribed the ship's original passenger list held by the National Archives to recreate every landing card as part of a series of exhibitions.

The original Empire Windrush passenger list is currently on display at the National Archives in Kew

"The passenger list provides a wealth of information... The addresses are particularly interesting because they provide some insights into the next stage of the individual's journey [and] some additional context about their life in the UK," Dr Price says.

The team also created a database, external which "quickly demonstrates that the range of passengers was much wider and more varied than is often realised", he explains.

So what does it tell us about those who gave their proposed address as London?

Who were the passengers?

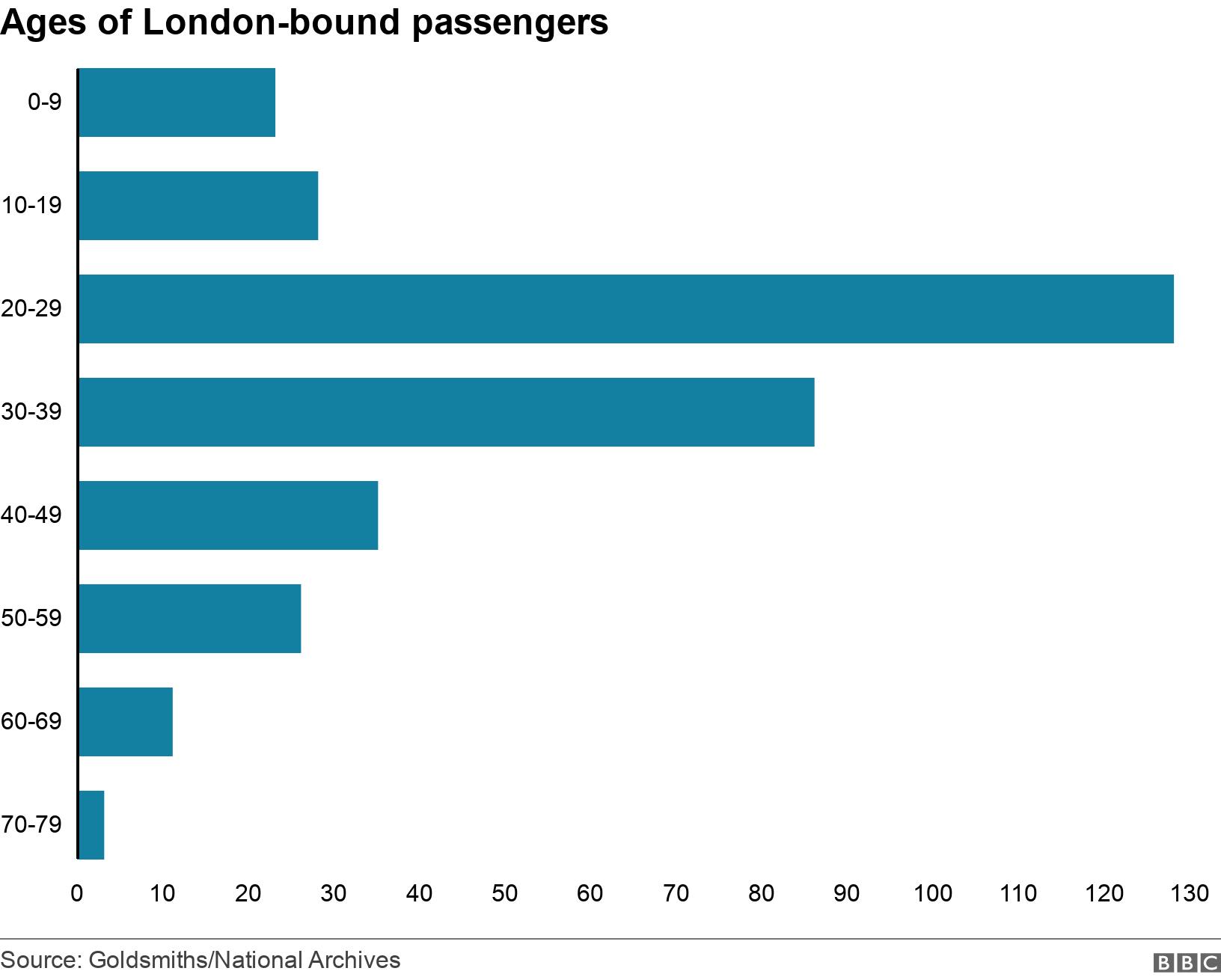

According to the database, the capital was the most popular destination for passengers with 340 of those on board giving an address in the city as where they were planning to stay.

Of those, 249 were male and 91 were female, while there were 301 adults and 39 children.

The youngest was a baby named Colin Beeston who was from Bermuda and was only nine months old when he left the ship. Married couple Henrietta and William Tucker were the two oldest passengers going to London, both being aged 75.

The stated occupations of those onboard varied enormously.

The largest number were termed household domestics, including people such as housewives, servants and cleaners. Other featured occupations were plumbers, electricians, dressmakers and cabinetmakers, as well five musicians, two chauffeurs and a Catholic priest.

Surprisingly, Jamaica-born Sam King - a leading member of the Windrush generation who famously became the first black mayor of Southwark and was credited with helping to co-found the Notting Hill Carnival - does not have a London address, with his destination on the passenger list given as Birmingham.

Also not included in the 340 are the 236 Caribbean migrants who had no planned accommodation and spent a few weeks living in a shelter underneath Clapham South Tube station until jobs and a home were found.

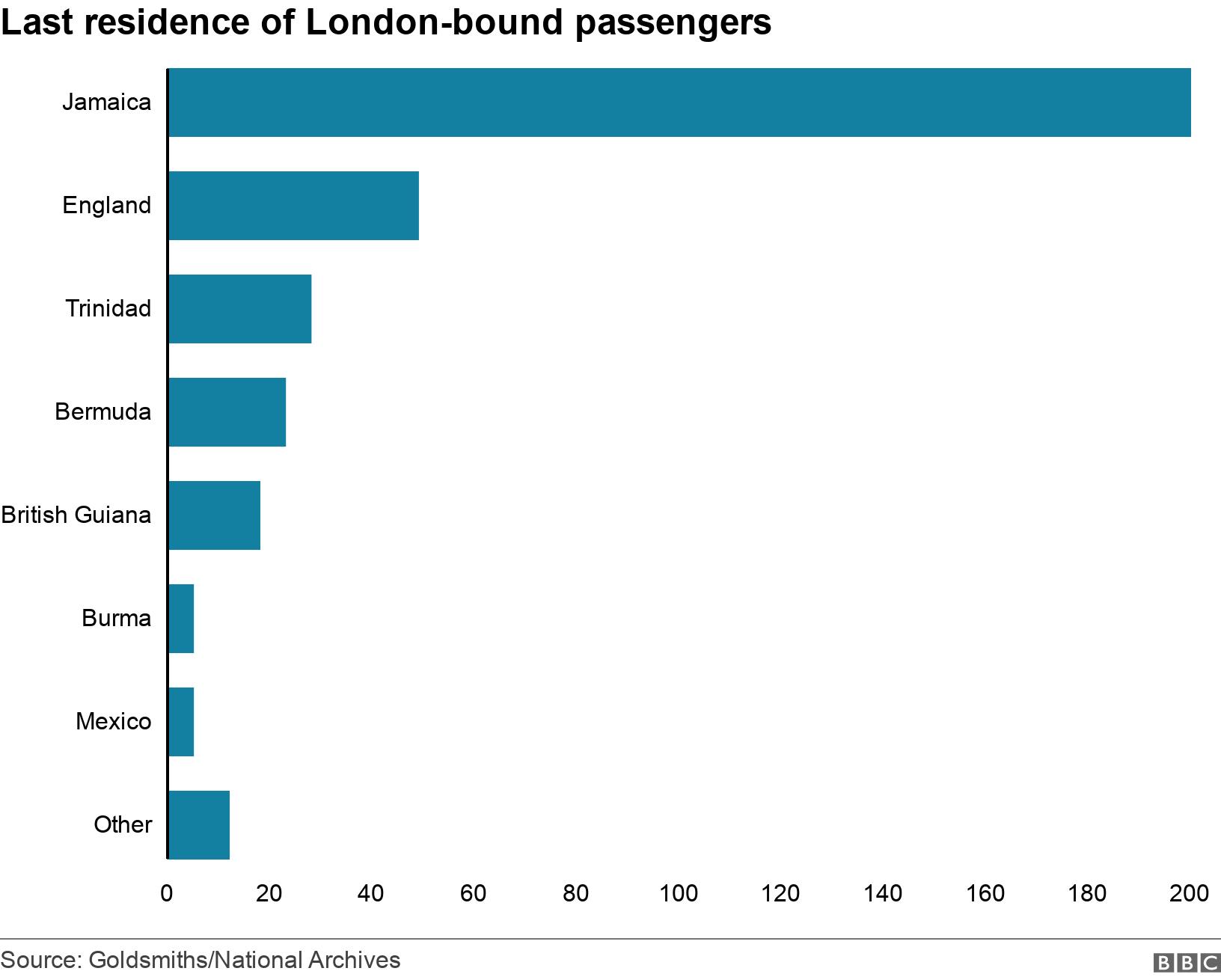

While the ship became synonymous for bringing over people from the Caribbean who helped rebuild a war-torn UK, the previous residences of those with proposed London addresses shows how diverse the passengers on board were.

The ship had called at Port of Spain in Trinidad, followed by Kingston in Jamaica, Tampico in Mexico, Havana in Cuba, and Bermuda as it returned to the UK from Australia.

Therefore while the vast majority of those going to London were from the Caribbean, there were also 50 who were from the UK, while other last residences included Burma, New Zealand and Italy.

According to Dr Price this was because the original purpose for the ship's journey was to stop at various ports to collect servicemen as it returned the UK.

However, things then changed when it got to the Caribbean.

"When arriving at Kingston, Jamaica, there was still plenty of space left on the ship, so the enterprising captain advertised cut-price tickets on the troop decks to anyone wishing to travel," he says.

As such not all of the passengers with London addresses were planning to stay in the country, with 66 saying they were going on to other parts of the British Empire and three planning to head to other countries.

"For many, their journey on the Empire Windrush was a relatively routine occurrence, undertaken by people who travelled back and forth to various parts of the British Empire for work or for other purposes," says Dr Price.

"Although it was not exactly a 'regular' scheduled passenger ship it would appear that passenger tickets were sold and, as such, some passengers were using it simply as a convenient way to undertake their journey."

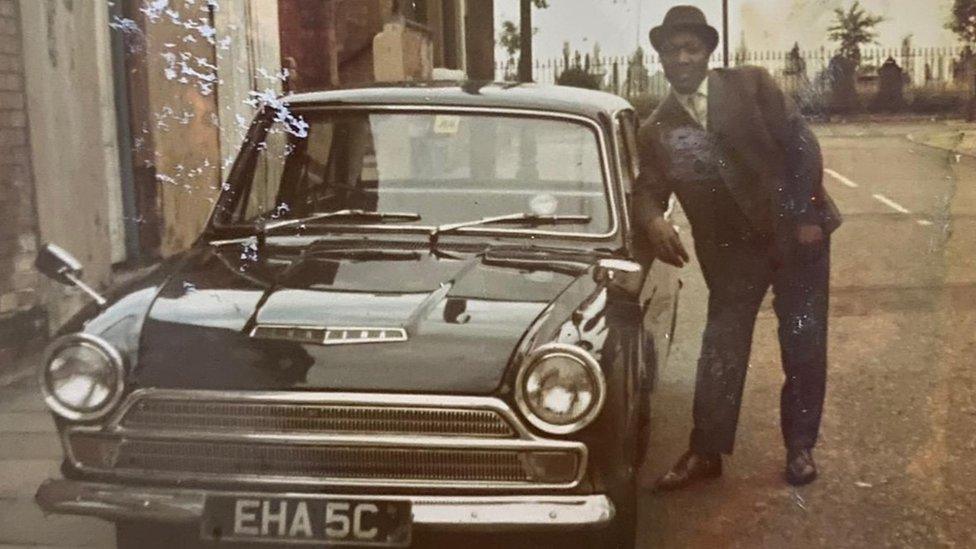

A diverse range of passengers arrived in England on the Empire Windrush

Meanwhile, 66 of those who had given their last destination as Mexico were Polish refugees who had fled their country during World War Two and were living in the Santa Rosa settlement camp, external having been given shelter there.

"Following the Polish Resettlement Act, external in 1947, Polish troops who had contributed to the Allied war effort were given support from the British government and assistance was provided for their relatives abroad to join them," Dr Price explains.

The Empire Windrush had instructions to collect these family members and five of those - Maria Bojczuk, her three teenage children and 46-year-old Stefania Urban - gave their proposed destination as London.

Where did they stay?

The passenger list shows that those heading to the capital had addresses all over the capital (you can see where they ended up on a this map, external).

For those returning to Britain their destination would have been their homes, while temporary addresses like hotels were provided by those who were simply using the ship as part of a longer journey.

Several migrants gave addresses for businesses where they were likely to have already been offered jobs which they were moving to the UK to begin, according to Dr Price.

For example, John and Hamil Stevens wrote Lloyds Bank in Pall Mall, while the four members of the Berger family noted Nestle's Milk Co in Eastcheap in the City of London as their addresses.

"Servicemen often provided the address of the base they were returning to," the senior lecturer adds.

Many of those who arrived in the UK on 22 June 1948 were there to help fill post-war labour shortages

Some addresses used by people from the Caribbean also have multiple passengers attached to them, such as 15 and 18 Collingham Gardens in Earl's Court where there were hostels run by the Colonial Office to accommodate students who had come to the UK to study.

However, intriguingly none of those who included those addresses were actually officially listed as students.

"This all suggests that, for some of the Windrush passengers, their arrival and their subsequent onward journey and accommodation could be a rather ad-hoc affair," Dr Price says.

Follow BBC London on Facebook, external, Twitter , externaland Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hellobbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published16 June 2023

- Published19 April 2018

- Published2 June 2023

- Published5 January 2016

- Published21 June 2018

- Published4 May 2023