The airman from Sierra Leone who was shot down over Nazi Germany

- Published

Johnny Smythe flew 27 missions with the RAF during World War Two

John Henry Smythe, an RAF navigator from Sierra Leone in West Africa, was shot down and captured in Nazi Germany in 1943.

War had broken out four years earlier when he was 25 years old, and Johnny volunteered to join the fight against fascism after a call from Britain to its colonies for recruits. Again and again, he and his comrades risked their lives in the skies above occupied Europe.

After he was liberated from a prisoner-of-war camp, he would go on to become a senior officer aboard the Empire Windrush and then an amateur courtroom talent of such promise he was invited to train as a barrister in England. As the attorney general of Sierra Leone, he would meet President John F Kennedy in the White House.

But as a black man in the clutches of a murderously racist Nazi regime, how did Johnny Smythe survive the war?

The RAF navigator was part of a Short Stirling bomber crew

With bullets ricocheting off the barn he was hiding in, he knew he had to give himself up. Exhausted and bleeding heavily, the RAF flight lieutenant stepped out to face the enemy.

"You can imagine their shock, seeing a 6ft 4in (195cm) tall black man in the middle of Germany," his son Eddy Smythe explains. "They just couldn't understand what they were seeing!"

A navigator with 623 Squadron, Flt Lt Smythe had already flown 26 missions as a Short Stirling bomber crew member.

The flights would take him over the English Channel, France and Germany, and were always high risk. The life expectancy of RAF bomber crews was alarmingly low.

"It was most dangerous over Berlin where there was the heaviest anti-aircraft fire and you were met by German fighters," says Eddy, a 62-year-old development surveyor. "He used to talk about how scary it was flying in the dark with shells bursting all around you."

Flt Lt John Smythe was appointed OBE for his wartime efforts

Smythe's plane was hit by enemy fire on numerous occasions, but somehow he had always made it home.

"A lot of the guys loved flying with him," his son says. "They'd say: 'Johnny, you've got black magic. Your plane gets shot up but you always get back.'" But then came the deadly 27th mission. As Eddy describes it: "That was when his luck ran out."

It was 18 November 1943. As the crew approached Berlin to launch their attack, their plane was hit by anti-aircraft fire. One engine exploded. Smythe was struck twice, in his side and groin.

They managed to drop their bombs but, with an engine gone, the Short Stirling had become an easy target.

"A German plane began circling and strafing them with bullets," Eddy says. "The upper gunner was hit and another engine burst into flames. The captain then gave the order to bail out."

Smythe landed in some woods. Dosed up on morphine and weak from the loss of blood, he reached a barn where he thought he could hide and sleep. "Except he lit a cigarette as he went in and was spotted," his son says.

"Lucky" Johnny Smythe had been captured.

The life expectancy of RAF pilots during World War Two was very low

In his later years, he spoke to the BBC about what it meant to be a black man taken prisoner in the heart of Nazi Germany.

The number of people with African heritage living in the country during the war was in the thousands.

The experiences of each person differed. Some were targeted because of their race through measures such as sterilisation and exclusion from education and certain jobs. Others found themselves in concentration camps.

Describing what he faced when he walked out of the barn, Smythe explained: "After you have been bombing a town, you're shot down and you're caught, the people are all against you whether you are black or white.

"But in the case of a black man it was worse, because I heard them shouting what I knew afterwards when I could speak a bit of German: 'Let's kill him.'"

The flight lieutenant was trained to use equipment such as a sextant for his role as a navigator

Military police intervened and the RAF officer was taken away for questioning. He was beaten during his interrogation before being transported to hospital to be treated for his shrapnel wounds.

"He chatted to German officers while he was there," Eddy says. "They told him: 'You are lucky, you're going to heal and go to a prisoner-of-war camp. We have to go back and possibly die'."

More questioning followed at a centre in Frankfurt, where Smythe was threatened with execution if he didn't co-operate with his captors. "You are a black man, you should not interfere in a white man's war," Smythe recounted being told.

"So I said 'if they're going to shoot me so be it, let them shoot me'."

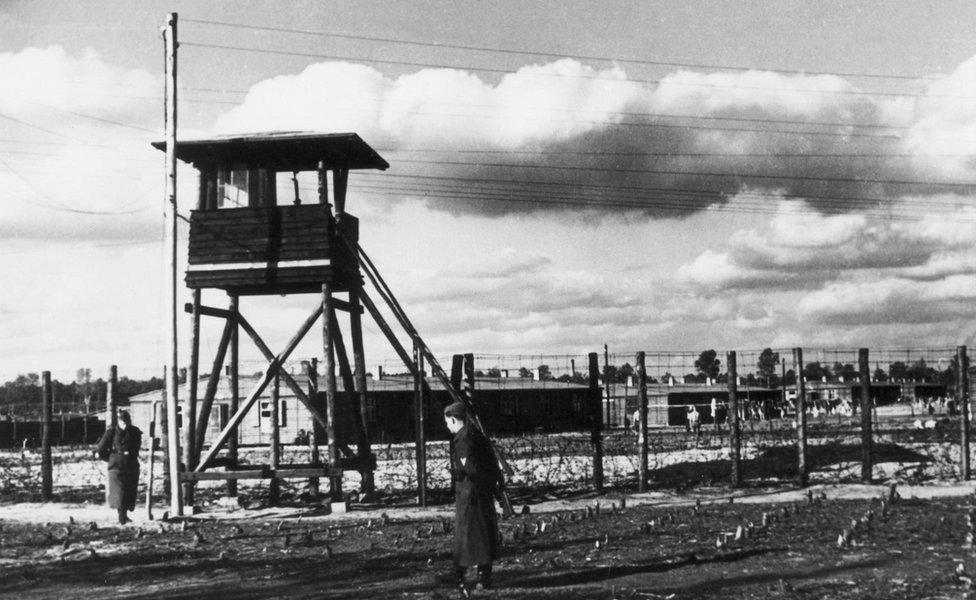

It turned out to be a bluff. He was transferred to Stalag Luft I, a prisoner-of-war camp in northern Germany that would be his home for the next 18 months.

More than 170,000 British armed forces personnel were captured during World War Two and imprisoned in camps like Stalag Luft III, as seen here

The flight lieutenant found attitudes towards him were respectful in the camp, his son says.

"He found no discrimination, in spite of him being the only black person there for the first 12 months. He'd say it was only when he looked in a mirror that he remembered he was black."

Propaganda was used to sap the captured men's morale. The German officers would say the Allies were losing, but the inmates managed to build a radio and were able to learn this was untrue.

Eddy says they "woke one morning and all the guards were gone". The Soviets were only hours behind the fleeing Germans, as they approached the camp on 30 April 1945. Within a couple of weeks, a liberated Johnny Smythe was transferred back to Britain.

He returned to London, where he had trained in St John's Wood after first arriving in the UK in 1941, and was offered a post with the Colonial Office.

His main role was to look after the welfare of demobilised airmen from the Caribbean and Africa.

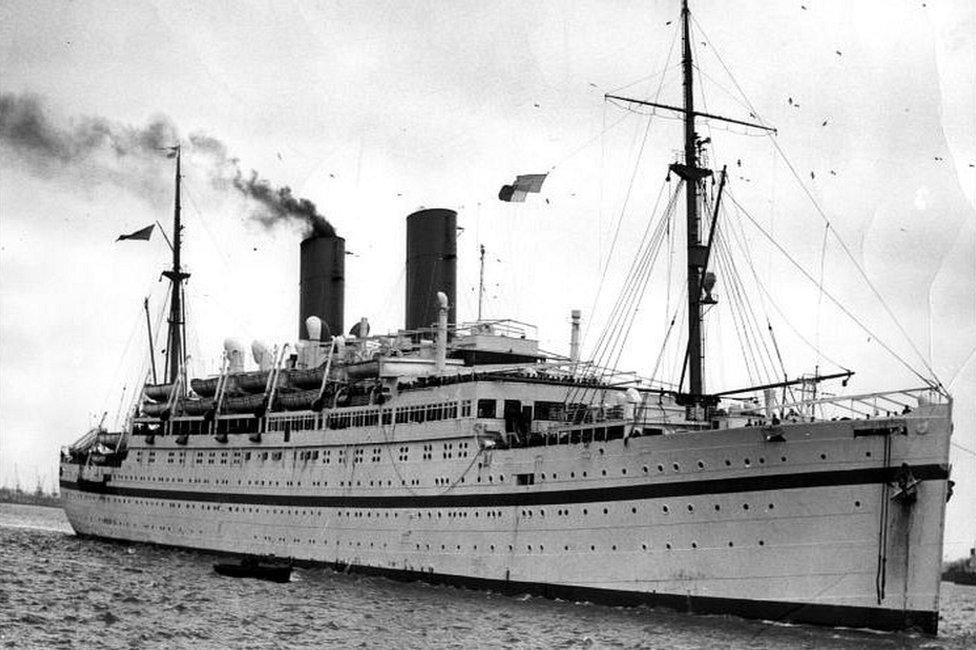

In 1948 he was deployed as a senior officer on a captured German troop ship, which was tasked with taking former military personnel back to their homes in the Caribbean.

That craft was the Empire Windrush.

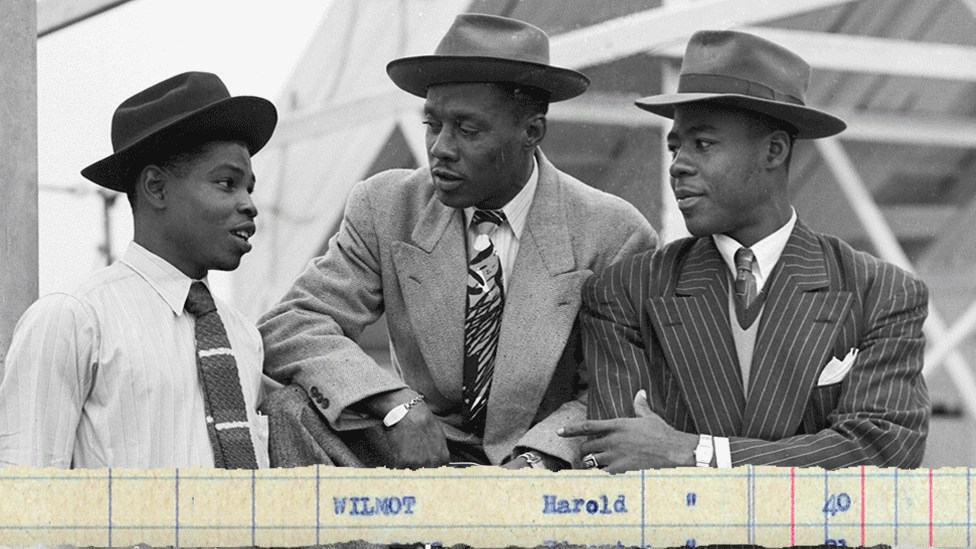

Johnny Smythe, seen here second on the left, was a senior officer on the Empire Windrush

"They had been dropping people back but when they got to Jamaica, a labour officer came on board. He told them the economy was struggling and the returning men were going to have a very hard time, so he asked if they could go back to Britain.

"Dad contacted the Colonial Office and they told him that as he was the senior officer, he should come up with the plan," Eddy says.

With the help of the Windrush crew, Smythe interviewed each of the men to learn about their skills and qualifications.

"He explained to them that there would be opportunities in the UK but it would involve lots of hard work. En masse, the men said they wanted to return, so he filed a report and the Colonial Office said 'fine'."

Workers from Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and other Caribbean islands arrived in England on the Empire Windrush

When the Empire Windrush made its way into Tilbury docks in Essex, Smythe was baffled by the greeting they received.

"As they sailed into port there were planes flying overhead with banners," Eddy says. "My father was wondering what was going on. On the dockside there was his fiancée, holding up a newspaper with the headline 'Smythe on the job'.

"In those days there was lots of gratitude for what those men had done in the war. They were welcomed back as heroes."

Immigrants arrived in the UK to help fill post-war labour shortages

A chance encounter in court led Smythe to his next adventure.

As part of his work looking after the welfare of demobilised RAF personnel from Britain's colonies, he was asked to defend a man who faced a court-martial. In spite of having no legal training, he prepared the case and won.

The same thing happened a few months later and the same judge happened to be presiding. "The judge asked if he had thought about a career in law," Eddy says. "He gave my dad a letter of introduction to the Inns of Court.

"That letter was really what got him in. It would have been very, very unusual for a black person at that time to get into the Inns of Court."

Once qualified as a barrister, Smythe returned to Sierra Leone's capital Freetown, where he had been born in 1915. He became a Queen's Counsel and Sierra Leone's attorney general, and would later set up his own practice.

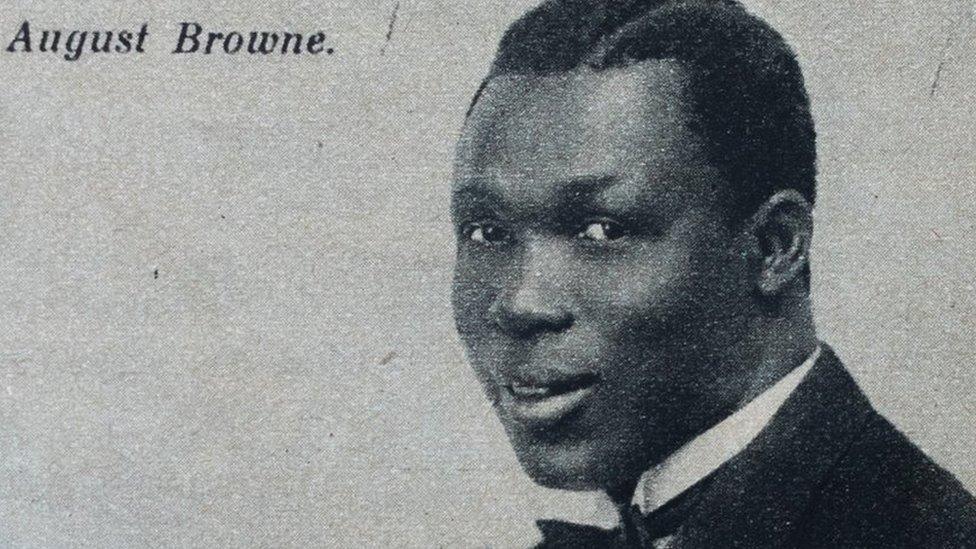

His work took him around the world. In the 1960s he was asked to go on a tour of the US to promote African culture. While there he was invited to the White House and met President John F Kennedy, who was happy to provide a favour for a fellow World War Two veteran.

"The injuries my dad sustained during the war left him with a bad back," Eddy says. "He mentioned he had a stiff back to the president (who himself had back trouble) and Kennedy said: 'I've got a great chiropractor here. Why not let him treat you?'"

People arriving in the UK between 1948 and 1971 from Caribbean countries are considered to be the Windrush generation

Eddy's father also spoke about a remarkable encounter at a cocktail party at the British ambassador's residence in Freetown.

He explained that he had been discussing the war with the German ambassador and described to him the place and date he had been shot down. Turning pale, the ambassador replied: "I got my first kill on that day; I shot down a British bomber."

"I asked my dad what he felt about meeting the man who may well have shot him down," Eddy says. "He said they just threw their arms around each other and embraced."

After he retired, Smythe moved back to the UK, to Thame in Oxfordshire, where Eddy was then living.

Towards the end of his life, the war hero's injuries began to take their toll. "They did an X-ray when he was in hospital aged in his 70s and even found shrapnel in his intestine," his son says.

Johnny Smythe died in 1996 and was buried in Thame.

"My father was an unusual character," Eddy says.

"If you walked in a room, you just always knew he was there."

The Museum of London has recorded an interview with Eddy Smythe in which he speaks about his father's eventful life. It can be found on the museum's website., external

- Published3 October 2020

- Published22 May 2019

- Published21 June 2019