Met Police: Communities traumatised by stop and search

- Published

The BBC spoke to police on patrol in Barking

A senior Metropolitan Police officer says stop and search, when done poorly, has traumatised communities in London.

Deputy Assistant Commissioner Ade Adelekan said the force recognised it needed a "reset".

He added that the Met still believed the tactic was a "significant tool" in saving lives but that it could also reduce trust in the force.

"Communities tell us, not just about stop and search, that we tend to do it to them rather than with them."

It follows a highly critical review of the force by Baroness Casey in March, which called for a "fundamental reset" of stop and search, saying black Londoners were at least three and a half times more likely to be stopped than white Londoners, and that black Londoners were "over-policed and under-protected".

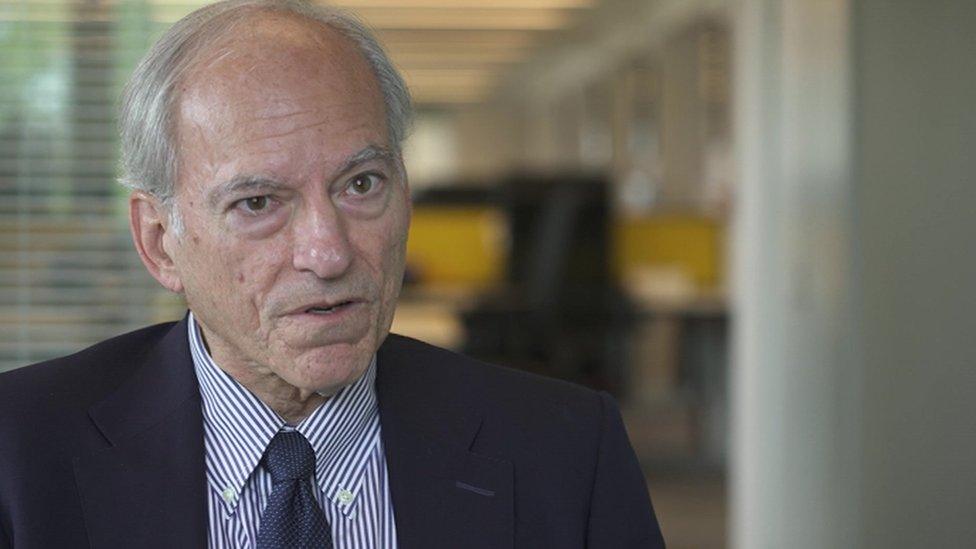

Deputy Assistant Commissioner Ade Adelekan: "We are really committed to listening to our communities and responding accordingly"

The Met is trying a new approach, described as "precision stop and search", in parts of London that have been identified as the worst affected by knife crime, led by the force's first chief scientific officer Prof Lawrence Sherman.

His team has ranked all 679 of London's council wards, calculating the areas with the "highest harm", using the sentencing guidelines for each weapon-enabled offence reported there over the period of a year. "In some of them people get stabbed and in others the weapon is used as a threat but no-one is hurt," Prof Sherman explains.

He says the data has identified the area around the Southbank and Stockwell, parts of Brixton and three wards in the borough of Barking and Dagenham in east London.

"Most of London doesn't have a knife-crime problem, but the places that do have concentrated knife crime may not have been getting enough attention in ways that would be proportionate," Prof Sherman says.

Sgt Timothy Willis said that when on patrol sometimes police can forget the impact stop and search has

The approach sees two officers, on foot patrol in those areas, at key times of day.

"We're not asking officers to change the way they apply the law, or to change the amount of stop and searches they're doing," says Det Supt Brittany Clarke, as we join her on a patrol of Northbury, in Barking. She says they are carrying out about one search every three days there.

The officers have been given "procedural justice" training, which teaches them to use respectful language when carrying out a search and to explain why they're doing it.

"Police take it for granted they should be trusted, but they don't explain their motive," Prof Sherman explains. "They don't say why we're here, they don't say something like: 'This is one of the most dangerous places in the city for knife crime, and so we have a special duty to protect people like you.'"

Sgt Timothy Willis, one of the officers on patrol in Northbury, says the training has been helpful: "We get almost numb to stopping people and searching them, and we forget the impact that has on the individual."

Angela Menzie, who stops to chat to the officers on the high street, says she agrees that police need to improve the way they carry out stop and search, adding that her son has had negative experiences.

Angela Menzie says police "need to treat that person like their mother, like their sister"

"Most people, they agree with stop and search, but it's the way it's done. Especially with our younger black boys, black girls, they're traumatised already from what they see, what they've heard, what they've experienced."

She said police "need to treat that person like their mother, like their sister, and explain what they're doing so these young people aren't frightened".

Other residents the BBC spoke to say they would like to see change, but are sceptical about whether this will happen.

Yuran Alexander Tarelho says he does not view police as people who can help him

"I don't really see the police as people who can necessarily help us," Yuran Alexander Tarelho says.

He adds that he is worried about the safety of his younger sister, following the recent fatal stabbing of 15-year-old Elianne Andam in Croydon.

But he says police "tend not to understand who they're going after".

"Let's be honest, we have young individuals that are not involved in anything that are being stopped, that are being harassed."

"Precision stop and search" is being led by chief scientific officer Prof Lawrence Sherman

One concern is over whether the patrols could simply move crime somewhere else - although Prof Sherman explains that research has shown this does not happen.

"It makes sense logically but the facts about crime, as we know from interviewing thousands of active criminals, is there are only certain places they want to commit the crimes, and if you make it hard for them there, they don't go someplace else, they just don't do the crime," he says.

Deputy Assistant Commissioner Ade Adelekan says the Met recognises "we need to take the public with us". He adds that community panels will observe police work and give their feedback, and says officers' body-worn camera footage will be compared from before and after they received training, to see what difference it has made.

He says the force will be assessing if it has helped to improve trust and driven down crime at the same time.

"I cannot speak for what happened before, but I can tell you that what we are really committed to do is to listening to our communities and responding accordingly," he explains.

"There are no guarantees here; we are trying."

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published19 September 2023

- Published21 March 2023

- Published20 July 2023