War hero: 'I do not know how long I spent in my grave'

- Published

Sub Lt Jack Easton GC died aged 88

Medals awarded to a man who was buried alive in an explosion during the Blitz have sold at auction for £110,000.

Sub Lt Jack Easton was a member of the Admiralty's secretive Land Incident Section when a parachute bomb detonated in London's East End.

When eventually pulled from the debris, he had a fractured skull, a broken back and broken legs.

The decapitated body of his assistant, Ordinary Seaman Bennett Southwell, was discovered six weeks later.

The seven medals sold for £110,000

On 8 October 1940, a mine fell through the roof of a house in Hoxton and came to rest in an awkward position.

The surrounding area had been evacuated and Sub Lt Easton decided to try to defuse it where it was, to avoid disturbing it.

As he worked, OS Southwell passed him the tools. They had not been working for long when suddenly the device dropped and started ticking.

Winston Churchill visited the site where Sub Lt Easton and OS Southwell tried to defuse a bomb

Knowing they had only 12 seconds until it detonated, they both ran. Sub Lt Easton was buried under rubble from the explosion but OS Southwell was caught in the blast.

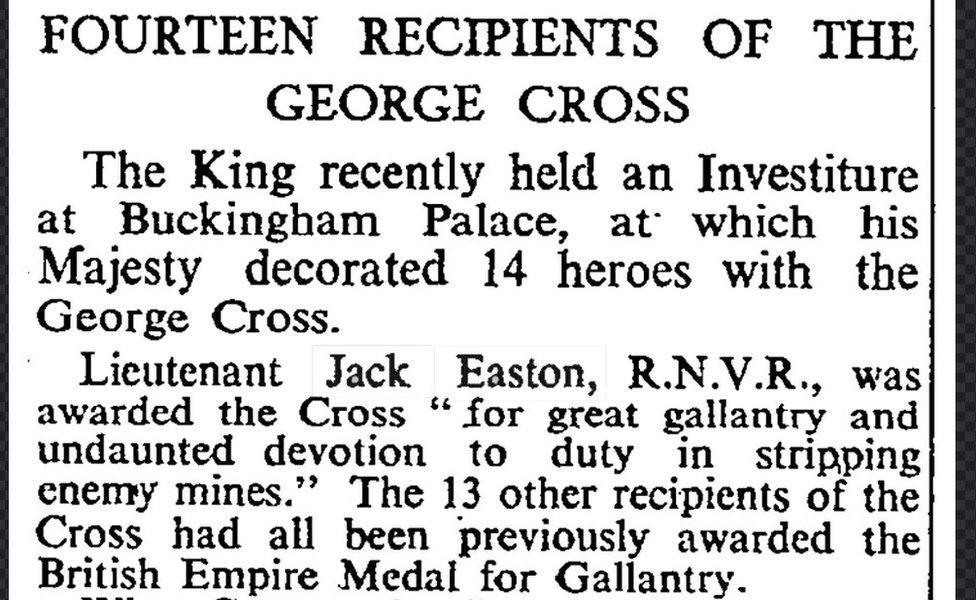

Both Bennett Southwell and Jack Easton were awarded the George Cross - and Sub Lt Easton's was among a group of seven of his honours that sold at Noonan's Auction House.

OS Southwell's medal is on display at the Imperial War Museum.

Sub Lt Easton recounted his experience in a book called Wavy Navy: By Some Who Served.

Sub Lt Jack Easton's George Cross

"I did not know this would be my last assignment in mines disposal work when I left the Admiralty before breakfast that morning and was carried by car to Hoxton.

"At the back of the minds of us who did this work was an acceptance that there probably would be a 'last'.

"In defence of our sanity, perhaps, to stop us leaping from the cars that carried us to each assignment, or maybe just in case we began to think ourselves heroes, we did not dwell on this probability.

"It was there. But suppressed. If and when the 'last' mine came… well it came.

"Several of our section had found it; some, less fortunate than I, did not live to tell the story.

"My 'last' buried me in rubble for several hours with my back broken and other injuries, and it kept me in plaster for the best part of a year."

Jack Easton received his award in person while Bennett Southwell's was accepted by his widow

Sub Lt Easton had previously made safe 16 such devices, including one which had crashed through the roof of the Russell Hotel in Bloomsbury and ended up hanging from the chandelier in the main dining room.

The hotel owner tried to give Lt Easton a cheque for £140 and an offer of Sunday lunch for his family for life.

Both had to be rejected "as a matter of honour".

The Russell Hotel in Bloomsbury where a mine ended up hanging from a chandelier

The medals in the lot were:

George Cross Sub Lt. Jack Maynard Cholmondeley Easton, R.N.V.R. 23rd January, 1941 For great gallantry and undaunted devotion to duty

1939-45 Star

Atlantic Star

One clasp, France and Germany

Defence and War Medal 1939-45

Coronation 1953

Jubilee 1977

HMS Vernon was a shore establishment that took on responsibility for mine disposal

Sub Lt Easton attended a crash course on defusing explosives after volunteering for a "secret mission".

"There were many speculations as to why the mines had not exploded, even on contact. But that their mechanisms would start operating again to even the slightest movement or tap (as you might start a stopped watch by the gentlest finger-nail tap on its face glass) was something known.

"Our warning that the mine was alive again was the ticking of its mechanism, and when we heard that we knew we had a maximum of 12 seconds to get to safety.

"In certain situations, this time margin meant nothing.

"One Sub Lt who died was dismantling his first mine. No part of him was found, not even a uniform button or badge. He just disintegrated."

Jack Easton GC trained as a solicitor and joined his grandfather's law firm in the City of London

He also described the feeling when he approached the location of the bomb he was to defuse.

"Those solitary walks towards the location of a mine always reminded me of the last scenes in the pictures of Charlie Chaplin.

"I had the feeling that a vast audience was watching the way I walked. It had been a last scene for several men I knew.

"It was the usual type of working class home in the East End of London, one of a continuous structure of two-storied, drab erections, more miserable than usual because of the stillness, the emptiness of the houses.

"Through the windows one saw the miserable interiors, the little proud possessions in ornaments, plants, enlarged and coloured photographs of soldier and sailor sons, the parlour luxuries of poor folk.

"The mine hung suspended through a hole in the ceiling, its nose within six inches of the floor. The parachute was wrapped partly round a chimney pot and again caught on an ancient iron bedstead in the room above."

Hoxton hospital was bombed in October 1940

When the bomb started ticking, Lt Sub Easton used the 12 seconds to fling himself into an above-ground bomb shelter across the road.

"To this day I do not know how long I spent in my grave. I was buried deep beneath bricks and mortar and was being suffocated. My head was between my legs, and I guessed my back was broken, but could not move an inch. I was held, imbedded."

After being taken to hospital, the Admiralty sent three cases of champagne and told him to listen to the 18:00 news, in which the George Cross was announced.

Remarkably, after a year in plaster, Sub Lt Easton made a full recovery.

He died in 1994, aged 88.

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk

Related topics

- Published20 June 2016

- Published23 October 2015

- Published24 October 2015