Factory-made homes: How prefabs sprouted from the ashes of war

- Published

This half-timbered prefab in Catford, south-east London, was built by German and Italian prisoners of war - some homes from that time are still lived in today

Eighty years ago, in the shadows of World War Two, Parliament held a debate on the chronic shortage of housing.

Hundreds of thousands of homes had been destroyed. High explosives and incendiary devices blew apart large areas.

Fires finished off what the bombs hadn't flattened.

Many Londoners were made homeless in the Blitz, the eight months of intensive bombardment in 1940 and 1941.

Some of the displaced went to camp in Epping Forest - and more than 180,000 slept on the underground platforms of the Tube each night.

These were barely even short-term solutions. Britain needed something more.

And so, with the Housing (Temporary Accommodation) Act 1944, external, the prefab was born.

A UK100 or American prefabricated house in the grounds of the Tate Gallery

Prime Minister Winston Churchill announced a 12-year plan for the building industry when peace came.

The Ministry of Works had come up with Emergency Factory Made Houses, or EFMs.

They devised an ideal floor plan of a one-storey bungalow with two bedrooms, inside toilets, a fitted kitchen, a bathroom and a living room.

The homes would be detached and surrounded by a garden to encourage householders to grow fruit and vegetables, and would have a coal shed.

Soon better known as prefabs than EFMs, the homes were cheap to produce and, for many, an improvement on their previous living conditions.

The London Passenger Transport Board Tube station platforms with bunks so Londoners could sleep underground

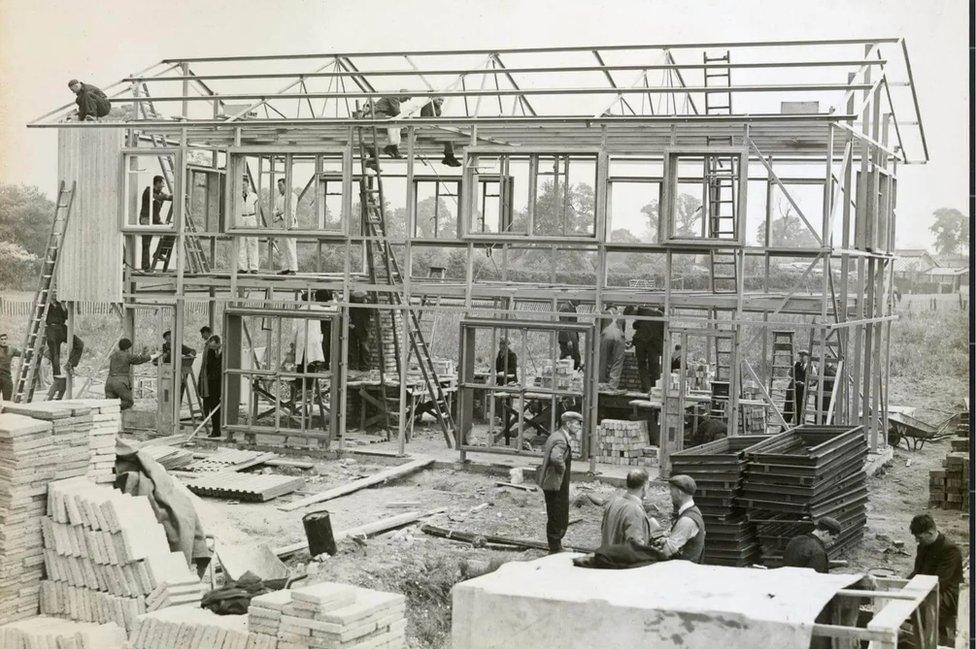

Construction of Uni-Seco prefabs in 1945 on a site damaged in the Blitz, in Greenwich

In May 1944, an exhibition was held at the Tate Gallery to display prefab designs, including the American (designed by the US Federal Housing Administration), the Uni-Seco (a kit that could be assembled in various combinations) and the Airoh (to be produced by aircraft manufacturers immediately after the war).

Architect Sam Webb was six when he went to the Tate show after his home was bombed.

He told the Prefab Museum, external: "It was all so clean and bright. This house was warm. Ours was so cold that in winter you didn't want to put your feet down the bottom of the bed unless you had a warmed-up brick wrapped in a towel.

"There were huge queues to enter each house. People just waited patiently in line. The war had trained them for that, queuing for buses, queuing for trains, or coal, or food. We stood in line for everything."

The Uni-Seco was one of several prefabs displayed at the Tate Gallery in 1944 - these ones are in Brixton

In the first decade after the war, nearly 500,000 homes were built using some form of prefabrication.

Originally intended as an interim solution until the country could return to building permanent homes with traditional materials, 156,623 prefab bungalows were built between 1945 and 1949.

Each was expected to last for a decade. About 8,000 remain today. A few dozen are listed by Historic England, external, and eight decades after they were produced, people still live in them.

Also known as the Aluminium Bungalow, AIROH stands for Aircraft Industries Research Organisation for Housing

Wartime and post-war shortages and austerity meant designers and builders had to develop innovative solutions - materials for prefabs included precast concrete, aluminium, asbestos cement, timber and steel.

In 1943 the Ministry of Works established an experimental demonstration site in Northolt, west London, where 13 houses were built to show various types of materials, plans and construction.

A British Iron and Steel Federation prefabricated house at the Ministry of Works' testing ground in Northolt

These little houses with all the mod cons, full of light and with heating systems (the kitchen and the bathroom came in one part with a wall in between, which contained the piping for both rooms) formed thought-out estates, with footpaths and greens.

Priority was given to families with young children, and those of servicemen. And everybody was starting afresh with the same sort of home.

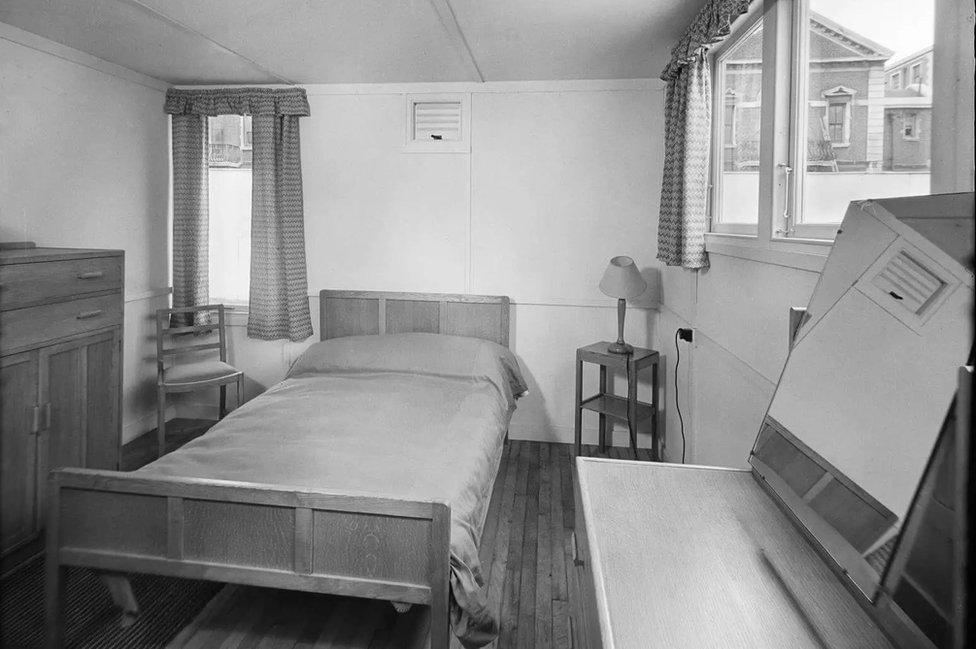

Utility Furniture in the bedroom of a Tate Gallery prefab

Of course, when homes were destroyed in bombing raids, not just the bricks and mortar were lost - furniture was too.

In 1940, a Timber Supplies Committee ended the unrestricted supply of wood for civilian use and considered the problem of replacing fixtures, fittings and furnishings.

By October 1941, only a sixth of the total supply of timber was available to the civilian sector - and by September 1942 the manufacture of civilian furniture was prohibited, except under licence.

Newly engaged Marcelle Lestrange looks at her permit for utility furniture

The Board of Trade selected the firms to receive the wood and imposed production programmes.

A small allocation of wood - and only of the poorest quality - was given to the making of civilian furniture, with the Utility Furniture Scheme being introduced at the end of 1942.

People could only buy the furniture if they had a permit, which were issued to newly married couples, expectant couples, bombed-out householders and those with children who had outgrown their cots.

Women making utility furniture which will only be available by permit

In 2009, six prefabs were listed in south-east London - they are part of the largest surviving post-war prefab estate in England.

Built between 1945 and 1946, the bungalows on Persant Road in the Excalibur Estate, Catford, are a mixture of types and were constructed by Italian and German prisoners of war.

Historic England cites them as a "unique example of prefab estate planning on a large scale" in what was one of the most heavily bombed boroughs in the capital.

And architecturally, the Uni-Secos are of interest as structures built using the innovative system of prefabrication displaying "modernist influences in their wrap-around corner windows and appearance of flat roofs".

The Uni-Seco kitchen features integrated shelving, fitted cupboards, a fridge and a fold-away table

Fewer and fewer prefabs remain - although some can still be spotted in the wild here and there.

Unassuming and cosy, they represent what many people today may never have - an affordable house to call their own.

Follow BBC London on Facebook, external, Twitter , externaland Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hellobbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published4 November 2015