The man hanged for printing his own ace of spades

- Published

"And I believe that's SNAP!"

As any card sharp, shark or sleight-of-hander knows, the ace of spades has a status that exceeds the rest of the pack.

Also known as a Spadille, it has nicknames including the Death Card and the Tax Card, and of the 52, is the most ornate.

For one London man in 1805 these three elements joined forces - the intricacies of baroque design meant he was caught trying to evade tax.

And he was hanged.

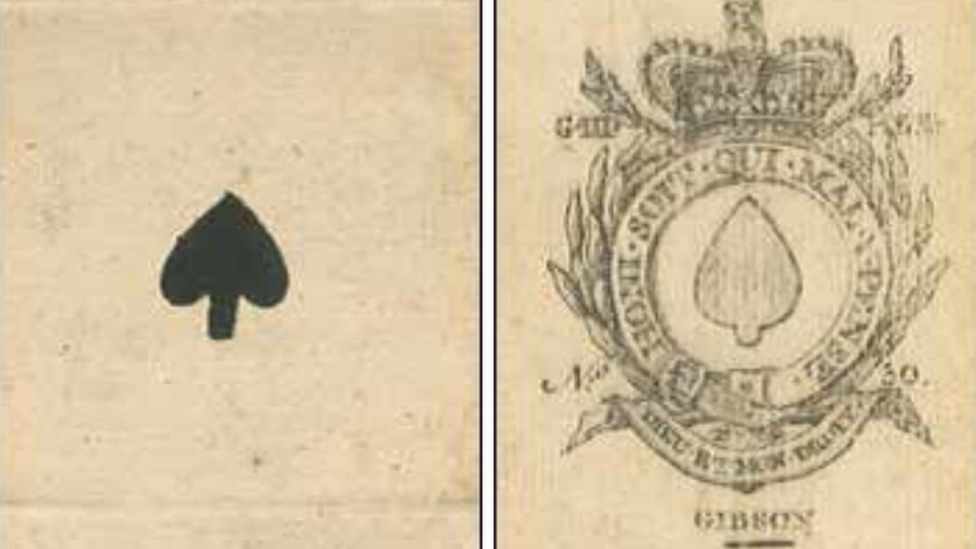

Aces of spades became difficult to copy without sophisticated metal printing plates

The taxing, in various forms, of gambling has always been a major source of income generation for the state.

The Office for Budget Responsibility estimates that in 2024-25 betting and gaming duties will raise £3.6bn,, external the equivalent of £124 per household, or 0.1% of national income.

Individual winners are not taxed on their profits - instead, the money is taken at the point of placing a bet. The government charges 15% on all gambling income for companies.

But between 1588 and 1960 there was a tax on physical playing cards - and in 1765 a process was introduced to make sure all vendors and makers would stump up the duty.

Makers had to supply the tax office with paper to match their other cards, and the tax office - also known as the stamp office - would print the ace of spades using engraved metal plates, a printing technology that was expensive and not widely available.

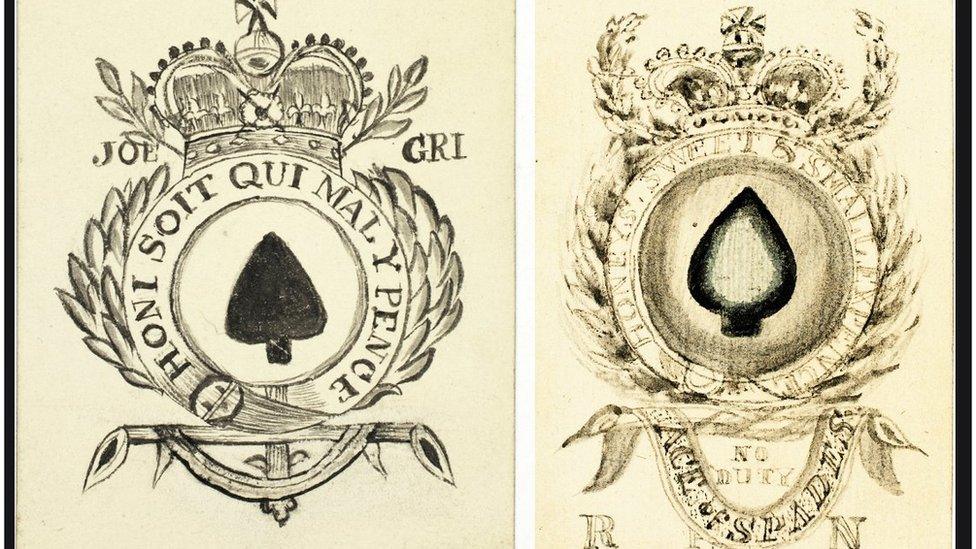

The maker would then buy the printed aces from the stamp office - thereby paying the tax. In order to make it more difficult to forge these aces, more and more elaborate designs were used.

The design of the ace of spades became increasingly more complex when the tax came in

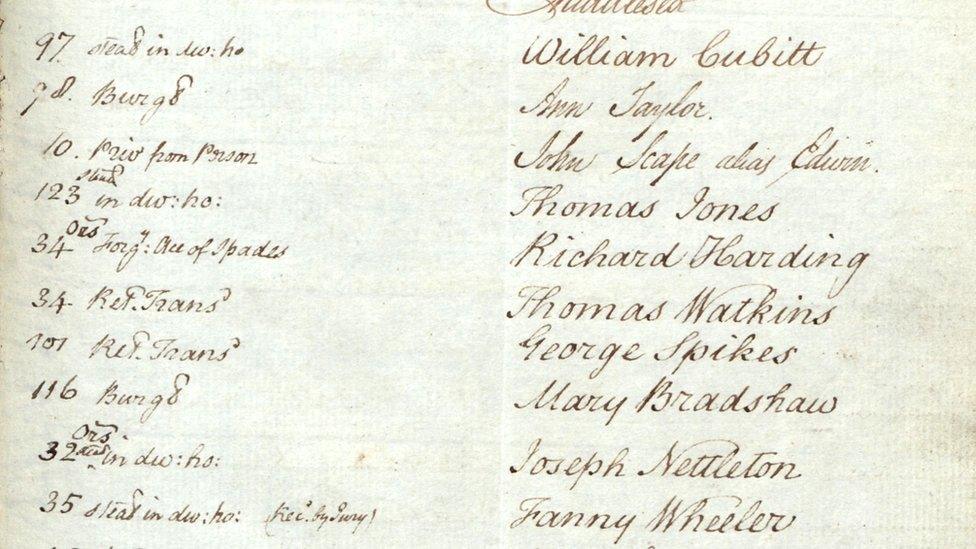

Richard Harding, a licensed card-maker with shops in Oxford Street and Grosvenor Square, carried on the manufacturing and selling of playing cards.

He did a roaring trade - but made very few demands of the stamp office.

A Mr John Hockey from the stamp office was put on the case. He started by buying six packs of playing cards from Harding's business and finding all of the aces were forged.

Obviously not one to leave things to chance, he continued to repeat his purchases until he had 90 packs of playing cards. All the aces of spades were forgeries.

The habits of this man, with his apparently insatiable desire for packs of cards, must have roused the suspicions of Harding for when his businesses and home were raided - not one forgery was found.

More side-eye than poker-face

War aces

In World Wars One and Two the ace of spades symbol was used as insignia by the 12th (Eastern) Division of the British Army and the 25th Infantry Division of the Indian Army respectively.

And during the Vietnam War, the ace of spades - known as the death card - was used in psychological warfare - US soldiers left the card on the bodies of killed Vietnamese and scattered them in villages during raids. Some reportedly stuck one in their helmet band as a sort of anti-peace sign.

Two US Marine sergeants stocking up on ace of spades cards before going on patrol

GIs believed the card would frighten and demoralise Viet Cong soldiers. It did not - there was no superstition attached to it in Vietnam - but did help the morale of American soldiers and Marines.

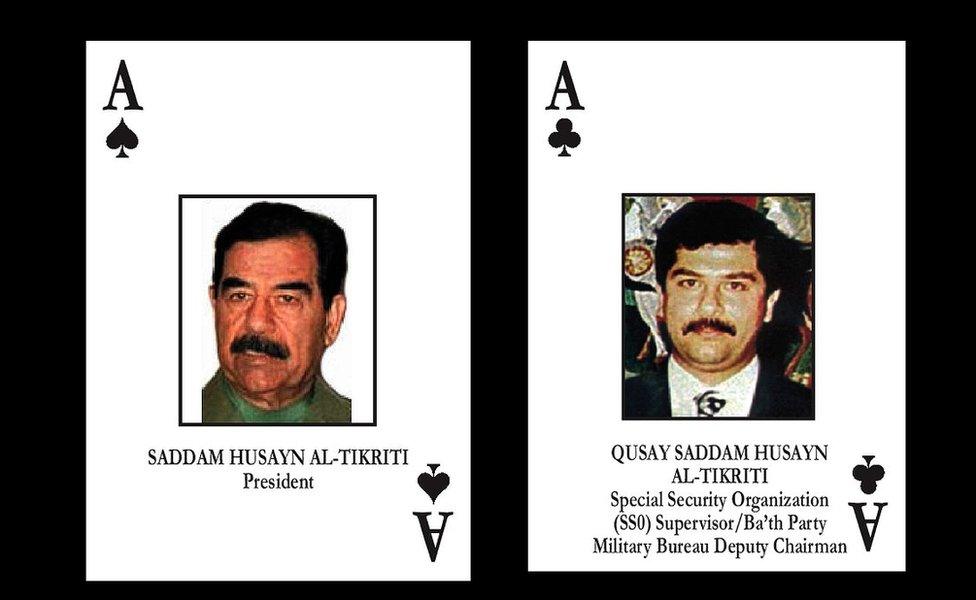

And in 2003, a deck of "most-wanted" Iraqi playing cards was issued to US soldiers, with each card displaying the picture of a wanted Iraqi official on it.

Saddam Hussein was placed on the ace of spades card and his son Qusay was allocated the ace of clubs.

In 2003, a deck of most-wanted Iraqi playing cards was issued to US soldiers

The dogged men from the stamp office were not about to give up and some of Harding's acquaintances were also paid a visit.

A Mr Skelton leased part of a building in his rear yard to Harding, where Harding would, in the words of the prosecution, "carry on his nefarious business".

Mr Skelton denied any knowledge of Harding's nefarious business. This, however, was cast into doubt when 2,000 aces of spades were found in his home.

More were found at his daughter's house, hidden in a basket of "foul linen".

The register of convictions shows Richard Harding as "forged the ace of spades"

Investigators also discovered, buried about a foot beneath the earth at the bottom of his yard, printing plates. In the privy, they found more.

They were for the aces of spades.

During the trial, John Hockey, the man who bought 90 packs of cards from Harding, told the Old Bailey he had paid the standard market rate - Harding wasn't therefore getting away with shoddy copies by selling them cheap.

So how had he managed to print aces of spades convincing enough they didn't raise the alarm with ordinary buyers?

Aces like the one on the right have "no duty" stamped on them and were meant for the export market

It emerged he paid for an associate, a stone-seal engraver called Hugh Leadbetter, to take copper-engraving lessons.

Mr Leadbetter told the court of an invitation to dine at Harding's home: "It was on a Sunday, and some little time after dinner he called me on one side and said, 'I shall be glad to speak to you'; and after that I went up stairs with him, and he said, 'Leadbetter, can you, or do you, engrave on copper?'

"I said, no, I could not, it was quite out of my profession.

"After dinner he shut me into a room, and gave me some gravers, and told me to do the best I could with them.

"He locked the door; I tried to do it, but finding I could not do it, I left off. He came into the room about the dusk of the evening, he said, 'Leadbetter, what have you done?'

"I told him I had done a little, I did not know whether it would do or no."

As it turned out, Mr Leadbetter's skills were not good enough - so he in turn paid another man, Mr Bunning, to do it.

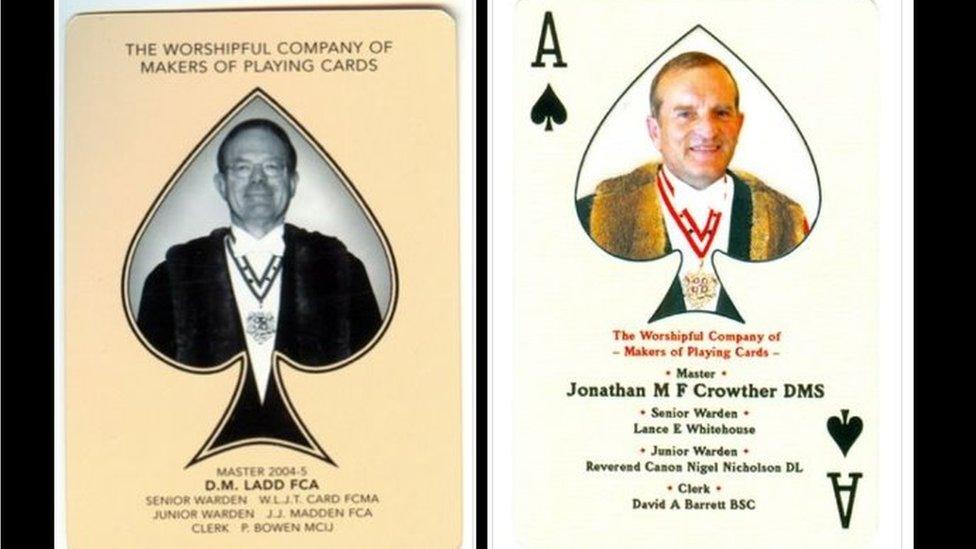

An annual pack of cards has been produced by the Worshipful Company of Makers of Playing Cards at the installation of each master, with a portrait in the centre of the ace of spades

Mr Leadbetter told Mr Bunning the work was for a legitimate stamp office engraver who was unfortunately too drunk to do his job with the necessary steady hand, and was therefore at risk of losing his business.

"Bunning said to me, 'Leadbetter, for God's sake, do you know what you are doing of?'

"I told him I did not. He then said, he could engrave these aces, but if he did, he must give them into the hands of a magistrate.

"A few weeks later Mr Harding came to me, and said, 'for God's sake, help me to bury the plates' for, said he, 'they have been searching my house'.

"And I buried them".

Harding left his defence to his counsel, and called seven witnesses who gave him a good character.

Yet on 21 September 1805 he was found guilty and sentenced to death. Two months later, he was hanged.

His remains were at St George Hanover Square Burial Ground in Bayswater until 12 March 1969, when he - and others - were removed to Lambeth and cremated.

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk

Related topics

- Published15 May 2024

- Published10 April 2024

- Published30 December 2021