Secret plan to demolish Manchester Town Hall revealed

- Published

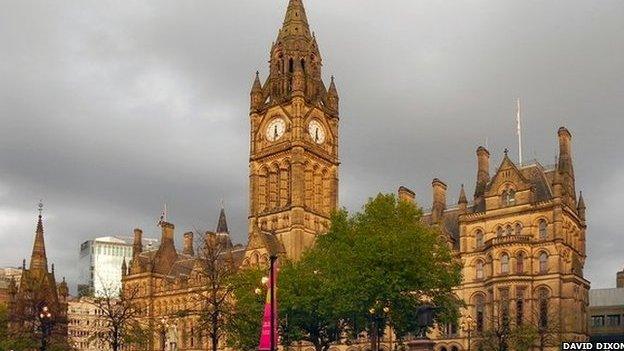

Manchester's neo-Gothic town hall could have been demolished had planners' visions come to fruition

.jpg)

The station that wasn't: Trinity mainline station in Salford would have created a bus terminal and river crossing over the Irwell

Manchester's much-loved Neo-Gothic town hall could have been demolished in the 1940s if planners had got their way. It was one of many outlandish ideas considered that never made it beyond the drawing board.

The proposals seem almost comedic now, with the benefit of 21st Century hindsight. Getting rid of the splendid Town Hall was one idea mooted by planners in Manchester in 1945. However, the idea, like many grand 1940s plans, ran out of steam as it came up against the obstacle of post-war austerity.

The revelation is just one of several found in eight city centre plans, spreading over four decades, which have been made public by the digital project Mapping Manchester, external.

Demolishing the Town Hall

In the post-war 1940s, Manchester Town Hall was not regarded as a masterpiece of Victorian architecture. It is now Grade II-listed. The planners at their desks in the Central Library regarded it as sooty and dirty and "not fit for purpose".

"They were in the Town Hall extension with its smooth lines like the central reference library looking at the Gothic pile and thinking: 'Let's do away with it'", said Dr Martin Dodge, of the University of Manchester.

Had it been replaced, it would have been a 1930s Art Deco building rather than a 1960s bunker.

"Part of the idea was to build a bigger civic plaza on Oxford Road with an exhibition centre and concert hall. The Town Hall would have been smaller," he said.

The 1945 plan aimed to remove the city's "congestion, dirt and ugliness" and added that "in many respects the Manchester citizen of 1650 was in a better position to enjoy a healthy life than the present-day inhabitant of Ancoats, Beswick or Hulme".

It mooted a solution to "remove the Town Hall and substitute a civic building of smaller dimensions" which would "leave room for a car parking space which would be particularly useful on ceremonial occasions".

Station across the river

Another proposal in the 1945 city plan was to build a new railway station, called Trinity, across the River Irwell in Salford.

The plans would have led to Manchester's other train stations being mothballed and a bridge being built across the river.

"If the train station had been built, it would have affected the whole gravity of the city, shifting it from Piccadilly," Dr Dodge said.

The new railway station aimed to make it simpler for travellers but British Rail derailed the plans by strongly objecting.

Elevated city walkways

The 1967 City Centre Map spoke of the "importance and value of civilised city life and the need for care and attention to be paid to quality of environment".

St Ann's Square in Manchester would be very different had pedestrianised walkways been built

It discussed connected pedestrian routes, such as a "ground level precinct" between the Town Hall and courts and "overhead pedestrian access across to the Market Place and St Ann's Square." Pedestrian ways would "provide safe and civilised conditions for shoppers and those going about their business in town."

While taking in the rise of the car, there was the need to make cities liveable and put cars underground in sunken trenches with big multi-storey car parks on the edge of the city.

"Elevated walkways was part of the beginning of the shopping mall and it was a way of connecting all these spaces together," Dr Dodge said.

"They weren't to know that these schemes would fail and they would be creating lifeless zones that were a paradise for muggers. They didn't know that these schemes were not going to work."

Concentric ring roads

In a sense, the vision of concentric ring roads has materialised with the development of the M60, Manchester's equivalent of the M25 around London.

However, the scheme in 1945 was bolder and proposed dual carriageways a couple of miles out of the city centre. The ring roads would have been further south of the city - beyond the boundary of the M60 - and extended south to Hazel Grove and the airport.

The plan proposed an inner ring road enabled by the construction of a viaduct over the Cornbrook Wharf of Pomona Docks. A survey emphasised "the great importance of this road in the future."

It spoke of "losses of movement which arise in a built-up area where pedestrians and vehicles share the same highway."

Had the concentric ring roads gone ahead, Dr Dodge said it would have been similar to the traffic gridlock witnesses on the North Circular Road in London.

"Like any big road building scheme, it doesn't cure the problem of generated traffic," Dr Dodge said.

"It would have benefited the drivers, but not the suburban residents," he concluded.