Elizabeth Gaskell: Why was the Cranford author considered so 'fearful'?

- Published

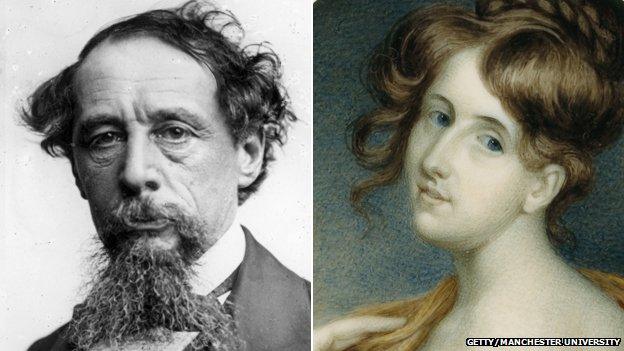

Charles Dickens and Elizabeth Gaskell didn't always see eye to eye

The Manchester home of the Victorian author Elizabeth Gaskell opens to the public on Sunday after a £2.5m restoration.

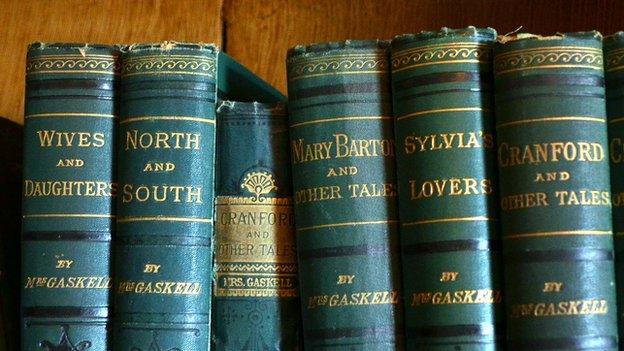

The 19th Century novelist wrote Cranford, North and South, and Wives and Daughters while living at the Plymouth Grove property between 1850 and 1865.

But who was Mrs Gaskell and has her work been unfairly overlooked when compared with Charles Dickens, Jane Austen and the Brontë sisters?

Family life

Charlotte Brontë described the Gaskell residence as being 'quite out of Manchester smoke'

Born in London in 1810, the then Elizabeth Stevenson moved to Cheshire the following year after her mother's death.

Her life with her aunt in the village of Knutsford would later inspire her novel Cranford, about life in a quiet market village.

At the age of 21, she married Reverend William Gaskell - with whom she would have four daughters and a son - and they soon moved to Manchester, which was then emerging as a centre of industry and radical politics.

The BBC drama Cranford revitalised interest in Mrs Gaskell

Their Unitarian Christian beliefs motivated them to help the poor, who were living in a squalor later described as "Hell upon Earth" by the German socialist philosopher Friedrich Engels, perhaps better known for writing The Communist Manifesto with Karl Marx.

The Gaskell family moved to Plymouth Grove in 1850 and while Elizabeth was delighted with their new villa, she fretted over its annual £150 rent - equivalent to £17,600 today.

In a letter to a friend, she questioned the morality of spending so much on a house "while so many are wanting" before concluding: "I must try to make the house give as much pleasure to others as I can."

"She's what we would recognise as a modern woman, as she's doing lots of different things at the same time," says John Williams, who for the last two years has been responsible for restoring the house to its former glory.

"She is a good wife to her husband, who has a public role, so she is also playing a public role. She is bringing up four daughters… [and] she is running a household with five servants - that's like running a small business."

Writing career

Gaskell's novels were often inspired by her experiences in Manchester and Cheshire

After losing their baby son in 1844 to scarlet fever, then a common cause of infant mortality, William encouraged Elizabeth to take up novel writing.

Her first book Mary Barton, published anonymously in 1848, was inspired by the lives of workers in Manchester. Its depiction of social problems won praise from eminent writers including Charles Dickens and Thomas Carlyle.

Janet Allan, chair of Manchester Historic Buildings Trust, says: "Her second major novel was Ruth, about the problems of an unmarried mother, which was actually burnt by some members of [her husband's] congregation… and he stood by her."

North and South, also made into a drama, depicted social unrest in 19th Century England

She adds: "She was a very courageous writer. She wasn't just the lady who wrote Cranford - there was lot more to her than that."

Comparisons have been drawn between Gaskell and fellow social commentator Charles Dickens.

"He is much more like a sledgehammer about poverty," says Williams, "whereas Elizabeth is subtle but if you read her carefully, she makes some powerful, aggressive points about the unfairness of life, the cruelty of manufacturers, the boorishness of wealthy people."

Gaskell, who died in 1865 leaving her final novel Wives and Daughters incomplete, was a versatile writer.

Her work ranged from a biography of her friend and author Charlotte Brontë to ghost stories, and Professor Helen Rees Leahy, who advised on the restoration of the Plymouth Grove house, says: "Her output varied - some were strong, others less so."

Social butterfly

The Plymouth Grove drawing room displays portraits of Mrs Gaskell (left) and her friend Charlotte Brontë

The Gaskells often entertained at their Plymouth Grove home, hosting a guest list that reads like a Who's Who of the mid-19th Century.

The famous orchestra conductor Charles Hallé gave piano lessons to Elizabeth's daughter Marianne in their drawing room.

Other visitors included the critic John Ruskin and the American author Harriet Beecher Stowe, who wrote Uncle Tom's Cabin. Elizabeth also welcomed her cousins, the Wedgwood pottery manufacturers.

But Jane Eyre author Charlotte Brontë, uncomfortable in large gatherings, hid behind the Gaskells' curtains when their doorbell rang.

Dickens invited Gaskell to contribute to his magazine Household Words and addressed her "Dear Scheherazade", after the storyteller in Arabian Nights.

Mrs Gaskell died soon after moving from Plymouth Grove

But she struggled to fulfil deadlines.

"Dickens was a professional journalist," says Allan, while Gaskell "found it very hard to keep to time sometimes, and to length. Sometimes he corrected things and she didn't know what he had done."

Their relationship became fraught and, in a letter to a colleague, an exasperated Dickens wrote: "Oh, Mrs Gaskell, fearful - fearful! If I were Mr G., Oh Heaven how I would beat her."

Elizabeth was also distantly related to the scientist Charles Darwin and even met the poet William Wordsworth in the Lake District. A keen traveller, she visited Italy, Germany and France with her daughters.

Her husband William, who preferred trips in Britain, sometimes stayed in the Lake District with the parents of a young Beatrix Potter, before the latter went on to write Peter Rabbit.

Mrs Gaskell's works have arguably been undervalued, but Professor Leahy hopes the renovation of the author's Plymouth Grove home will boost her popularity.

"Given that Austen, Dickens, Bronte and others have their 'houses' [to remember them by], it's timely that Gaskell joins their ranks."

- Published2 October 2014