Strangeways riot: Ex-inmates recall siege, 25 years on

- Published

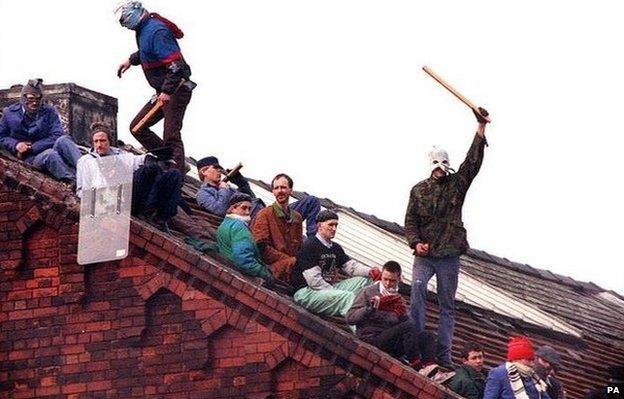

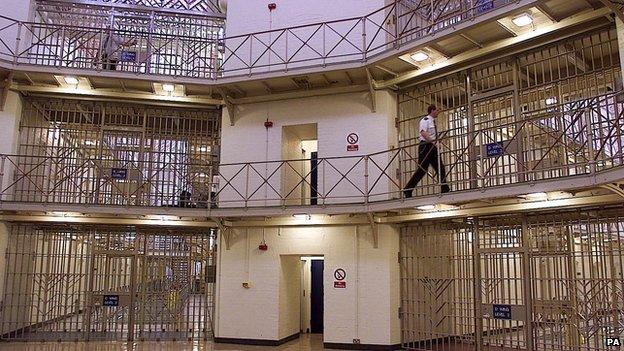

Prisoners communicated with the outside world from the roof of the prison during the siege

The Strangeways riot was the longest in British penal history and dramatically changed the way UK prisons were run. Twenty-five years on, four people at the centre of the siege explain their part in the drawn-out drama.

On Sunday 1 April 1990, about 300 inmates filled the Strangeways prison chapel, where they listened to a Church of England sermon.

One prisoner, Paul Taylor, interrupted proceedings by shouting out. It was the spark. Within minutes, the men inside had taken control of the chapel. Before long, a riot had spread throughout the prison.

Two people died and hundreds were injured during the ensuing 25-day protest against the Victorian jail's squalid conditions.

Television images of prisoners sitting on the roof of the building, some holding banners, were seen by people around the world.

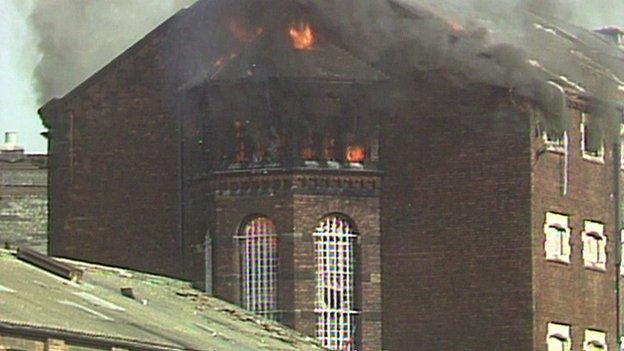

Fire ripped through sections of the prison during the 25-days of unrest

In an attempt to wear the prisoners down, the authorities responded by cutting off the electricity supply, spraying the roof with cold water and playing incessant loud pop music.

It did not work - inmates held out for almost a month, continuing to hurl both missiles and abuse.

The last five men to surrender were eventually carried from the roof in a hydraulic cherry picker on 25 April 1990.

Strangeways was built to hold 970 inmates but at the time of the riot it housed more than 1,600, making it one of the most overcrowded in Europe.

Three inmates were routinely housed in a cell designed for one. The most dangerous prisoners spent up to 23 hours a day in Victorian-built cells without any proper sanitation.

As one ex-inmate now puts it, they felt "something had to be done".

The instigator

"Twenty three hours locked in a cell, only opened up for one hour a day"

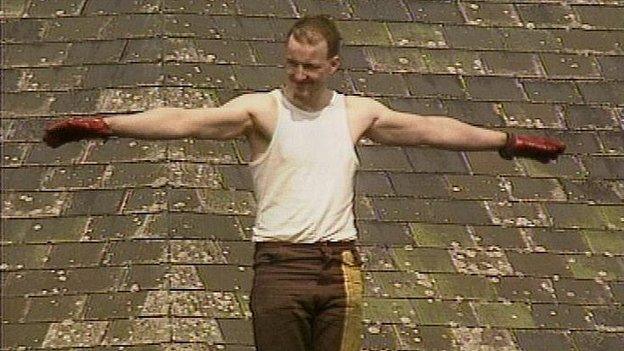

Paul Taylor, from Birkenhead, was the last man standing. He was also the first to take on the authorities. As he climbed aboard the cherry picker that plucked him from the prison roof, he raised a clenched fist in a final gesture of defiance.

Throughout the riot Taylor had refused to negotiate with the prison authorities and used a traffic cone to address assembled journalists.

Taylor had almost completed a two-and-a-half year sentence for chequebook fraud when he started a protest which, he insists, was meant to have been peaceful.

"I said it needed a 24-hour sitdown protest in the chapel - a show of strength," he says.

But the protest turned violent, with inmates assaulting prison officers and grabbing their keys.

After the officers retreated, Taylor started to unlock prison cells as many inmates made their way on to the roof.

They took up positions, tore off slates and pelted prison officers, police and emergency services with them before setting fire to the chapel and gymnasium, and wrecking cells.

Taylor, now 50, says: "It was very easy, they gave up the fight, they'd never been met with such resistance before."

Paul Taylor was regularly seen on the roof of the prison throughout the siege

Attention soon turned to the prison's C and E wings, home to alleged sex offenders who were awaiting trial. Several were severely beaten.

Rumours began to circulate, suggesting many had been tortured, killed and dismembered.

In truth, one prisoner, 46-year-old Derek White, lost his life as a result of injuries received in the mutiny.

The other fatality was a prison officer of the same age, Walter Scott, who died from a heart attack.

Prison mutiny

Taylor believes the riot ultimately led to prison reform and resulted in inmates being treated in a more humane and civilised way.

"I'm glad I took part in a protest that changed the course of history," he says, "because the prison service were reluctant to implement any changes whatsoever until Strangeways happened."

However he expresses regret over the beatings meted out to suspected sex offenders.

"We shouldn't have taken the law into our own hands," says Taylor, "because it detracted from our root cause of the protest - conditions and violence towards prisoners by prison staff and the general condition of prisoners."

Taylor was sentenced to a further 10 years for his role as ringleader. He was convicted of a newly created offence - prison mutiny.

The lifer

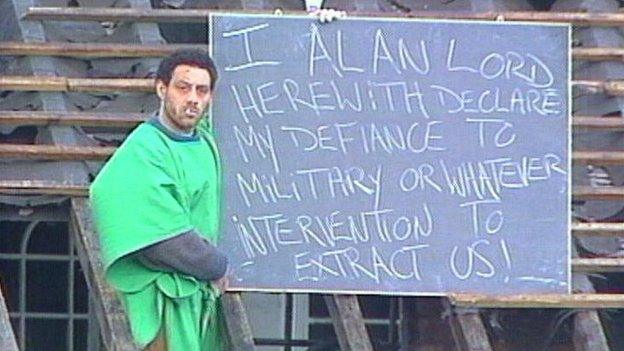

A classroom blackboard gave Alan Lord the change to bypass Barry Manilow

Alan Lord, who was convicted of murder after a botched robbery, spent much of the siege on the prison roof trying to negotiate with the authorities.

The now 53-year-old, from Manchester, says he began waving at the press who had set up nearby on Great Ducie Street.

"At the same time I could see prison warders and governors… and some of them were shouting and pointing up at me and gesticulating 'we're going to break your arms and legs when we get hold of you'.

"I remember turning down and saying to them: 'Who's got your prison now? We've got your prison'."

Police and prison officers tried to drown out his conversations with the media by playing loud music. Their weapon of choice? A well-known lounge crooner.

"There was a police car on the other side of the wall playing music by Barry Manilow and he was drowning out what I was trying to get across," says Lord.

"I went down to one of the classrooms, seen my golden opportunity, ripped the blackboard off, found the chalk and went back up to the roof.

"I set the board up and started writing messages and as a result of that, within minutes, Barry Manilow ceased - to everybody's relief."

He adds: "There was a lot of people dissatisfied with their treatment within that jail and as a result of a discussion it was decided that something had to be done."

Following the riot, Lord was also convicted of prison mutiny. He served a total of 32 years in prison and was only released on licence in 2013.

The editor

"You look back today... and think 'how awful that they didn't have these things at the time'."

The riot attracted an unprecedented level of media attention. With the absence of hard facts, some lurid headlines emerged.

On the morning after the riot began, the Manchester Evening News ran a story with the headline "20 DEAD" in response to reports that 20 body bags had been sent inside the prison.

Mike Unger, then the paper's editor, says the headline was only used in the first edition and was based on "really good information".

"We had a specific number of body bags - 20 - taken into the prison," he says. "We asked the ambulance authorities and the other authorities: 'What does that mean? Is it just there as a precaution?'

"They said: 'We take 20 body bags in, we expect 20 bodies to come out and you can draw your own conclusions from that'."

The prisoners responded by hoisting banners on the roof proclaiming "NO DEAD" and asking for contact with the media.

A Manchester Evening News reporter at the scene volunteered his editor to go into the jail to meet the rioters and assess the damage.

The prison suffered substantial damage during the siege and was later rebuilt at a cost of £90m

Mr Unger says: "The thing that surprised me most was that massive steel doors were literally torn off their hinges and thrown off the balcony, and you think 'How on earth can you do that?'

"There must be some sort of power that comes into you, extra adrenaline flows through you, and it got these doors off, it was an amazing sight."

During his visit, Mr Unger persuaded about 30 prisoners to give themselves up. In return, he agreed to print their demands in his paper.

"You look back today at those complaints and you think how awful that they didn't have these things at the time," he says.

"There was no dignity, being locked up for 23 hours a day, being force-fed Largactil [anti-psychotic drug] to calm them down. It was just appalling."

The governor

The prison governor insists he made efforts to improve conditions at the jail

Brendan O'Friel thought he was the victim of an April Fool's Day prank when he received a call to say a riot had broken out.

The prison's governor since 1986, he says his first priority was to evacuate about 1,100 non-rioting prisoners to other jails.

"The public would occasionally let off [saying] 'Why don't you shoot them?' or 'Why didn't you knock them off the roof with hoses?'

"Those roofs were 80ft (24m) up and I could just see myself or others facing a coroners' court or worse if we had a dead prisoner down there and we'd knocked him off using fire hoses.

"It's not an easy business managing a prison riot."

Mr O'Friel insists that while conditions were bad, he made great efforts to try to improve them during his time in charge.

But he concedes: "The way a society treats its prisoners is a real test of its civilisation - in 1990 we weren't really living up to the sort of standards that we should have had."

The aftermath

The rebuilt and refurbished prison was officially re-opened as HM Prison Manchester on 27 May 1994

Built in 1868 by the revered architect Alfred Waterhouse, Strangeways - complete with purpose built gallows - was designed to serve as an austere warning to Manchester's would-be criminals.

It was so badly damaged during the riots, repairs cost £90m before it was reopened as HMP Manchester. Its 234ft (71m) tower continues to dominate the skyline north of the city centre.

A major inquiry into the riot was carried out by a senior judge, Lord Woolf,, external whose report blamed severe overcrowding and described conditions in the months leading up to the disturbances as "intolerable".

He recommended several practices should end, including "slopping out" - the use of chamber pots in cells without sanitation - and housing up to three prisoners in a cell.

Slopping out officially came to an end in 1996, although it continued in some parts of the prison service for many years afterwards.

A major prison building programme took place in an effort to solve the problem of overcrowding.

However the prison population is now double what it was in 1990, with rising violence and suicides and a reduction in the number of prison officers.

On the 25th anniversary of the riot, Lord Woolf now says authorities need to examine why his recommendations on rehabilitation were not implemented.

"There are a few things that are better now than then, but I fear to say that we've allowed ourselves to go backwards and we're back where we were at the time of Strangeways," he says.

"What is needed is somebody who is younger and energetic to do another review of the prisons and take the prison situation out of politics."

Inside Out is broadcast on BBC One North West on Monday, 23 March at 19:30 GMT, and nationwide on the iPlayer for 30 days thereafter.

- Published23 March 2015