How 1985 British Airtours disaster changed air travel

- Published

Engine failure sparked the fire, which spread to the fuselage of the Boeing 737

Thirty years ago, catastrophe came to Manchester Airport when a packed passenger jet burst into flames, killing 53 passengers and two crew members. How did the disaster change air travel, and could a similar accident happen again?

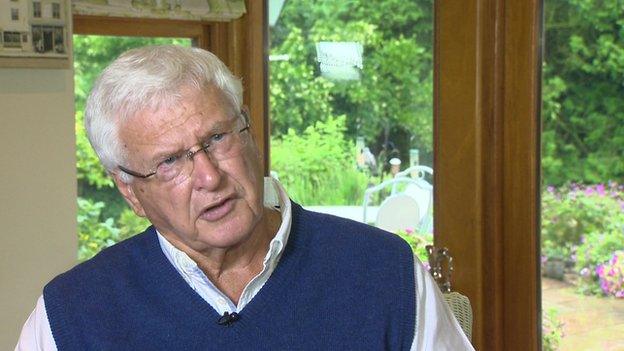

"Passengers were shouting: 'Fire! fire!' You're having a hundred thoughts. Where's your family? How were they ever going to get out?"

John Beardmore was among 131 passengers who boarded the ill-fated British Airtours flight 28M scheduled to leave for Corfu on 22 August 1985.

Hearing a loud thud as the Boeing 737 raced along the runway, the pilots at first suspected a burst tyre.

In fact, an engine failure had sparked a chain reaction, leading to a punctured fuel tank.

Take-off was abandoned and the plane was brought to a swift halt, but smoke and flames soon engulfed the rear of the aircraft, leading to panic in the cabin.

Many victims perished towards the rear of the cabin as passengers scrambled to the front exits

Mr Beardmore remembers the "curtain of black toxic fumes" that swept through the fuselage, as he remained trapped.

"When it hit me, I knew I had to hold my breath for as long as I could. If I breathed in, I was going to be in real problems," he said.

"My throat was blocked, my nose was blocked. My knees started to give way."

Nearly all 55 victims died from the effects of smoke inhalation as the passengers scrambled towards the front exits - one of which had become jammed - creating a bottleneck effect and stranding people at the back.

The subsequent investigation by the Air Accidents Investigation Branch led to a host of changes.

The probe found that the position of the aircraft when it came to a halt inadvertently made things worse.

A prevailing wind fanned the flames on to the fuselage and people were left with left little time to escape before thick smoke seeped inside.

John Beardmore said at first he thought he was the only survivor.

Mr Beardmore had boarded the flight with his wife Pamela and children Simon, 14, and 12-year-old David.

He said: "Everything started as normal. We almost got to take-off speed when suddenly there was an almighty thump underneath the aircraft. You knew it was serious.

"You could see the port side engine was glowing orange and there was a trail of black smoke following behind."

Mr Beardmore recalls the pilot then braking "incredibly hard".

He said: "The aircraft then quickly came to a controlled stop, and I thought at that stage we could all survive."

But Mr Beardmore said the gangway then filled up with passengers desperate to leave the plane.

"People started to scream at the back," he said. "Smoke was coming in. The windows were melting and suddenly there was thick, black smoke at the back of the aircraft.

The disaster led to many changes in the evacuation procedures of aircraft

"Queues weren't moving, the doors weren't opening and we were stuck. The aircraft was filling with fumes.

"I knew at that stage that if I had to take a second breath, I was going to go down.

"I stumbled forward. But I did notice at that time that the queue had seemed to have cleared. And as I stumbled and landed on the floor, I saw a shaft of white light, and I thought 'that's my opportunity. That must be fresh air'.

"I thought it must be a window and I crawled towards it. I just wanted fresh air. But to my amazement it was the front door, and there was the chute."

Landing at the bottom, Mr Beardmore says he at first thought he was the only survivor.

He then described his joy at hearing the voices of his family.

"[It was] the most wonderful sound I've ever heard."

Air Accident Investigation report: Main recommendations

In the event of a fire, procedures to be developed to enable the crew to position an aircraft with the fire downwind of the fuselage

Fire extinguishing techniques inside passengers cabins to be reviewed to deal with internal fires

Aircraft cabin materials to be fire resistant, including seat covers, wall and ceiling panels

Onboard water spray/mist fire extinguishing systems to be developed as a matter of urgency

A review to examine existing requirements over 'unobstructed access' to exits and if they need updating

The most experienced cabin crew should be distributed throughout the cabin

Source: AAIB report , external

As a result of the disaster, many aspects of aviation fire evacuation procedures have changed., external

Under today's rules, an aircraft on fire will always stop on the runway itself - rather than taxiing away from the strip - ensuring passengers are evacuated more quickly.

One of the most visible changes prompted by the disaster was the removal of a seat on each side next to the over-wing exits to create extra space.

The changes were supported by SCISAFE, a campaign group set up by relatives of some of the victims.

Mr Beardmore, of Congleton, Cheshire, was one of the founder members of the group, along with William Beckett, from Sheffield, whose 18-year-old daughter Sarah died in the disaster.

Mr Beckett recalled taking his daughter to the airport on the day of the fire.

It is now standard procedure for air traffic controllers to advise pilots about wind direction in the event of a fire

"Having got Sarah to the airport and checked in, ironically they said 'where would you like to sit?', and she said 'oh I'd like a seat at the back please'," he said.

"I said 'that's where smoking is'. And she said 'I know Dad, but it's safer at the back'."

Mr Beckett said his daughter believed this to be the case after a plane crash involving Japan Airlines had been in the news 10 days previously. The four survivors had been seated at the rear.

He said when he got home some friends called to say there had been an accident at Manchester Airport and he and his wife switched on the television.

"We saw the horrific pictures of that burnt out carcass of the aircraft which has been so vividly displayed so many times.

"I knew she was sat at the back and I thought 'I don't know how she will have got out of that'."

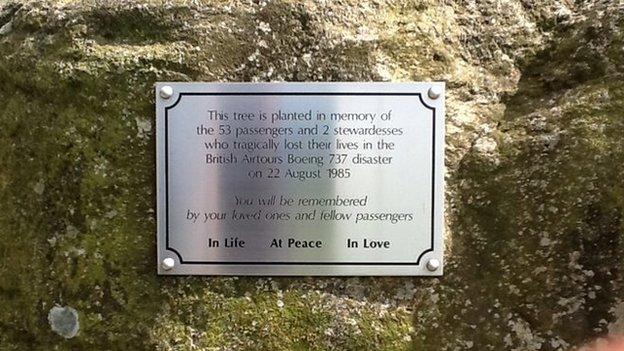

A tree was planted in memory of the victims close to Terminal 1 at Manchester Airport

But could such a disaster ever happen again, even with all the improvements to the safety of aircraft?

Patrick Smith, a veteran pilot and author of Cockpit Confidential, a book that answers common questions about commercial aviation, said it could not be ruled out.

"You can never engineer away every conceivable accident, nor every conceivable type of accident," Mr Smith said.

"What we can do, however - and what indeed we have done - is lower the likelihood of such a thing.

"Passengers will never fly in absolute safety, but they are certainly safer than they were 30 years ago."

- Published22 August 2010