Peterloo: The man who ordered a massacre

- Published

Mike Leigh's Peterloo retells the story of the peaceful protest that turned into a massacre

In 1819, a troop of sabre-wielding cavalrymen charged into a huge workers' rights protest in Manchester. The carnage that followed is the subject of a new film starring Maxine Peake. But who was the man who ordered the Peterloo Massacre?

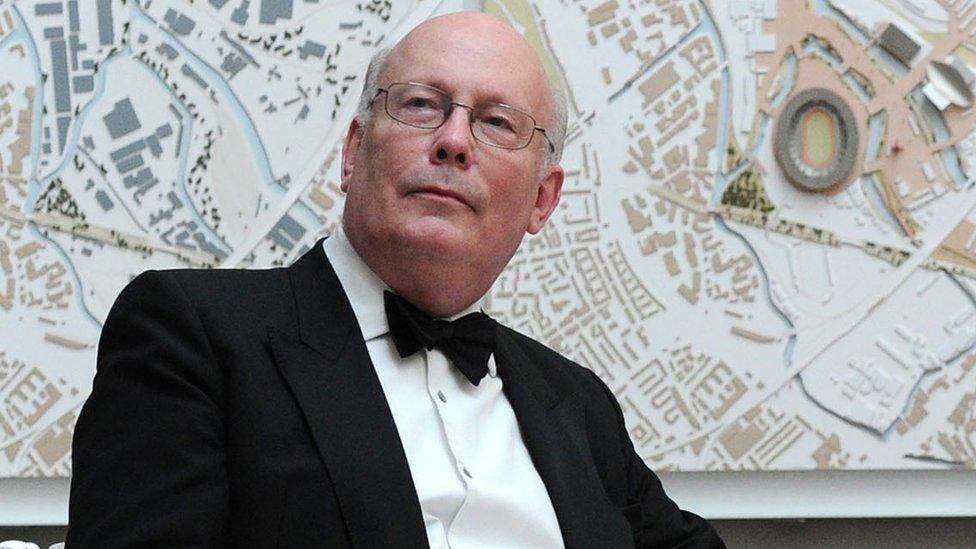

In a cafe in Sloane Square, the screenwriter and Conservative peer Julian Fellowes is contemplating his most notorious ancestor.

The creator of the hit ITV drama Downton Abbey is considering how, as a screenwriter used to drawing dramatic characters, he would assess the personality of William Hulton.

"Most characters have shades of grey because, on the whole, I think that in life people don't tend to be all evil or all good," Fellowes says.

"But actually William Hulton was pushing it for 'all evil'... I don't think he had much to redeem him."

The Oscar-winning writer is Hulton's great-great-great grandson - but this is not a source of pride.

He was, he says, a "cruel and horrible man".

William Hulton was well known for laying down the law and suppressing workers' rights

It was Hulton who, as a magistrate in north-west England, gave the notorious order for troops to violently disperse a peaceful, pro-democracy protest in the centre of the UK's first industrial city.

Screenwriters make much of a character's motives, so what does Fellowes think drove Hulton, who was born into a family of wealthy landowners?

"He was clearly a sort of hysteric," he says. "He was clearly terrified of any overthrow of the established social order."

Two hundred years ago, working-class people in Manchester and other industrial towns in the north of England were becoming increasingly vocal in their demands for political reform.

They were angry about the fact that most of the population could not vote, that corruption was rife, and that urban areas were grossly underrepresented in Parliament.

At least 50,000 people arrived at St Peter's Fields on 16 August 1819 to hear radical speaker Henry Hunt campaign for parliamentary reform.

At this time, Manchester had no police force so the Manchester Yeomanry was sent in to prevent any disturbances.

When Hunt began to speak the army tried to arrest him, and attacked anybody who got in its way. At least 11 people were killed and 400 injured.

The events soon became notorious in the press, where they were dubbed Peterloo, an ironic reference to the Battle of Waterloo that had taken place four years previously.

"It was only the barest of beginnings for any kind of workers' movement," says Fellowes. "But Hulton immediately went into some kind of overdrive, attacking a group that included a group of many women and many children - a lot of whom hadn't done anything."

Lord Fellowes says his ancestor had nothing to redeem him

He describes Hulton's heavy-handed response as a total misreading of the situation.

"Instead of lining up across the field and reading some sort of 'go home!' message, which clearly would have been the reasonable thing to do, he sent the yeomanry to a crowd who could not at once disperse.

"They were seen by him to be resisting but they were unarmed - they weren't resisting them with weapons."

The film Peterloo, which goes on general release on 2 November, is directed by Salford-born Mike Leigh, who is known for his gritty tales of working-class life.

"Although I don't think Mike Leigh and I are as one politically... I certainly agree with him about who were the bad guys," said Fellowes.

Peterloo star Maxine Peake backs the campaign for a bigger Peterloo Massacre memorial

Seven years before Peterloo, as a justice of the peace, Hulton had already sentenced four Luddites to death for setting fire to a weaving mill in Westhoughton, near Bolton. One of those hanged was a 12-year-old boy.

While history is full of monsters, historians tend to temper criticism when actions are in keeping with the standards of the time. But, in Hulton's case, even this does not save his reputation.

"They thought it was cruel and unnecessary and inhuman," Fellowes says.

"And so, in a sense, he was already an offender before the demonstration at St Peter's Field had ever happened.

"I feel extremely sorry for the men, women and children who were cut down at Peterloo.

"I think they were doing no more than making clear to those who would listen - the writing was on the wall, workers were bound to have some rights.

"What people like Hulton were trying to do was to fight history, and to fight the inevitable."

At least 50,000 people are estimated to have gathered in St Peter's Fields, although some estimates have the figure at twice that

Among those on the receiving end of the cavalry charge was Mary Heys, who was pregnant with her sixth child.

She had joined the hordes gathered near her ramshackle home in Oxford Street, which nearly two centuries later is occupied by a McDonald's restaurant.

Heys's story has been researched by her five times great-granddaughter Denise Southworth.

The 57-year-old said Heys was one of the massacre's "forgotten victims".

Indeed, estimates of the final death toll vary widely and the true number will never be known.

"She was trampled by a horse," said Ms Southworth. "Why would a woman in her 40s who was pregnant want to take part in a riot?"

The day after Heys was injured, she began having fits. Four months later she gave birth to a premature baby, Henry.

Denise Southworth says her great-great-great-great-great grandmother died after being injured at Peterloo

"[Mary] died just before Christmas - because she didn't die straight away, she wasn't counted among the dead," said Ms Southworth, who is Manchester born and bred.

"We gave more significance in my school in Manchester to the Battle of Waterloo than to Peterloo.

"I think it has been overlooked even in Manchester.

"I knew nothing about it - in my history books they were too busy talking about Napoleon and Waterloo."

Ms Southworth's sense of outrage has prompted her to join the Peterloo Memorial Campaign, which has the backing of Peterloo star Maxine Peake.

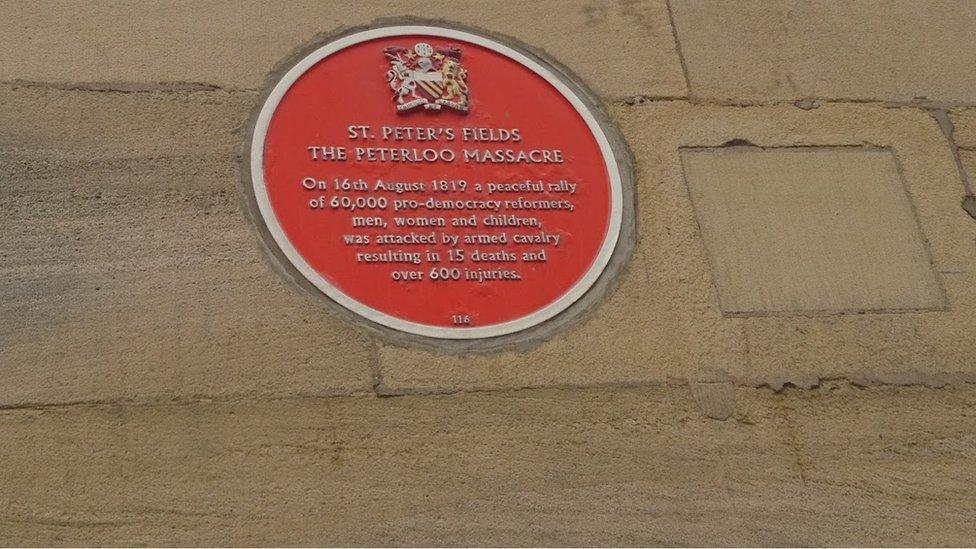

It is fighting for a permanent memorial to those who died, rather than just the small plaque which currently sits on the wall of the Radisson Hotel.

Ms Southworth said: "You look round here - the middle of Manchester - and see all these beautiful, fabulous, glass, expensive buildings - do people know what happened here 200 years ago?

"Do they know about how the ordinary working people came for a peaceful demonstration and were butchered?

"We are always told about Manchester's achievements, but let's not forget the spot where people were killed for trying get a decent standard of living.

"We owe it as educated people to remember those who didn't have a vote and did not have any rights."