Randox forensics inquiry: Forty drug-driving offences quashed

- Published

Police chiefs said the cases were dropped after a "most serious breach" of forensic science standards

At least 40 motorists convicted of drug-driving offences have been cleared after evidence of manipulation was found in the forensic testing process.

The motorists were banned from driving and in some cases fined, but their convictions have since been overturned.

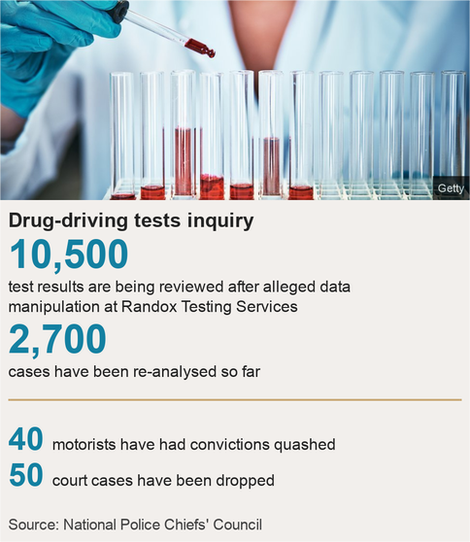

About 10,500 test results are being reviewed after alleged manipulation of data at Randox Testing Services.

The National Police Chiefs' Council (NPCC) described it as a "most serious breach" of forensic science standards.

A further 50 drug-driving cases have been dropped as a result of the alleged data manipulation at the firm's Manchester laboratory.

Randox has issued a statement, external revealing it had acted as "whistleblower" after discovering manipulation by its own staff in January 2017.

Police suspended all contracts with Randox, used by 42 of the UK's police forces, in November last year.

Greater Manchester Police has arrested two men, aged 47 and 31, who worked at one of its laboratories.

They were arrested on suspicion of perverting the course of justice.

Six others have been interviewed under caution, with one remaining under investigation as part of what Justice Minister Lucy Frazier described last month as an "expansive" criminal inquiry.

Hudgell Solicitors are representing 35 people who have already had their convictions quashed, and others who are pursuing civil cases seeking damages.

Andrew Petherbridge, the firm's head of civil liberties, said: "This is a national scandal which has had a devastating impact on the lives of the many people we are representing.

"People have lost their driving licences, and as a result lost their employment, struggled to pay bills such as mortgages and rents, and some have been unable to travel to see their families and children."

"Strain on life"

Scaffolder Luke Pearson, 26, from Manchester, was breathalysed and performed a road side drugs test for Greater Manchester Police after an accident in November 2016.

He tested positive for being over the drug-drive limit, and being an occasional cannabis user, accepted a 12 month ban and a fine of £480.

His conviction was overturned in February in light of the Randox investigation.

"It was devastating to me," he said. "I needed to travel to sites as part of my job as a scaffolder as we worked across the country, so as a result of me being banned I lost my job.

"I'd even been offered a job as a foreman for a company and they were prepared to give me a company car to travel around sites, but of course that opportunity was lost when I was banned."

Mr Pearson said that it put "a strain on life and on my relationship with my girlfriend" as he "struggled with bills and rent".

He added that he trusted "police and the legal system to look after you and do the right thing" and said the situation "takes away that trust."

Analysis

Danny Shaw, BBC home affairs correspondent

The scale of the operation to review the 10,500 Randox cases is unprecedented.

It began in January 2017 and is likely to continue until the end of 2019.

Randox, which is paying for samples to be re-tested by other laboratories, estimates it will cost the firm £2.5m.

Police are also likely to incur costs because of delays to other cases, while motorists whose careers and livelihoods have been affected after being wrongly banned from driving may sue for compensation.

But the most significant impact of this disturbing affair may be on public confidence in forensic science: can we be sure that the test results we almost take for granted are accurate?

In total, up to 2,700 cases have been re-analysed so far and two drug-driving cases that resulted in road deaths were referred to the Court of Appeal.

Both convictions were upheld but one motorist's sentence was reduced.

Two other non-fatal cases involving drug-driving have also been sent to the Court of Appeal. One conviction was quashed and the other has yet to be decided.

Ch Con James Vaughan, NPCC lead on forensics, said he could not remember a forensic science failure "of this magnitude".

He said re-testing was taking longer than expected because there was a "chronic shortage" of scientific expertise and accredited laboratories, leading to delays in providing toxicology analysis in unrelated cases of sexual offence and rape.

- Published27 November 2017

- Published22 November 2017

- Published1 March 2017

- Published10 February 2017

- Published21 November 2017