Could wristbands turn festivals into games?

- Published

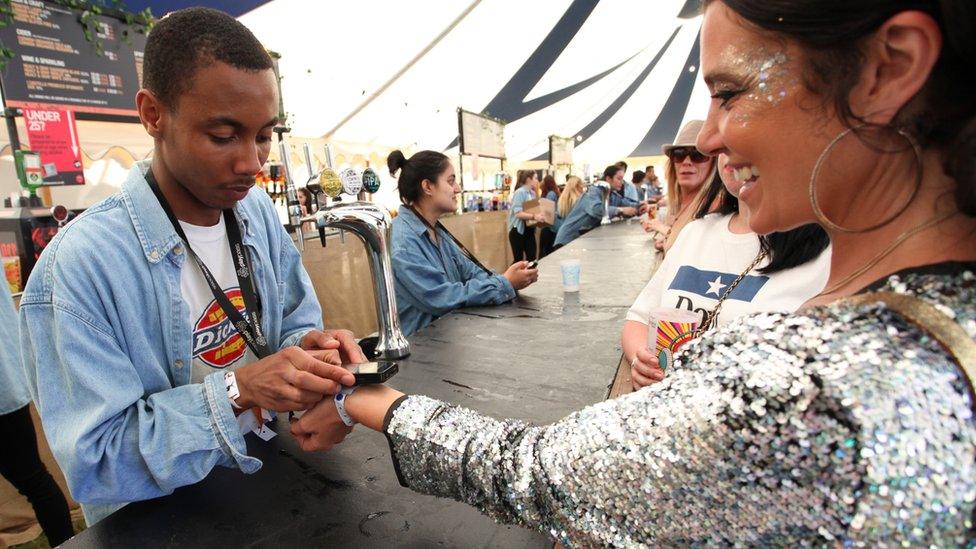

Wristbands have long been synonymous with music festivals, but what was once a simple, colourful loop of material now increasingly contains contactless technology. This allows music fans to pay for food, drinks or merchandise but festival directors are now taking the technology further, into the realm of "gameification".

This summer, Cheshire's Bluedot festival is celebrating the innovation behind the first lunar landings 50 years ago. But its organisers are hoping to make their own giant leap, taking contactless technology on its first tentative steps into the creative world.

Festival director Ben Robinson says it will allow visitors to check-in at stages, talks and stalls, creating a "mission log" they will be sent after the event, listing what they saw and giving further information.

Ultimately, he hopes to turn festivals into immersive gaming sites - something akin to Pokemon Go - where, alongside enjoying the festival site, visitors can unlock exclusive rewards. This might include entry to a restricted area for visiting a number of check-in points or free dishes if enough food is purchased.

Acts and artists can investigate creative uses, linking the wristbands to interactive apps and existing technologies, such as augmented reality, to give attendees something beyond the usual festival experience.

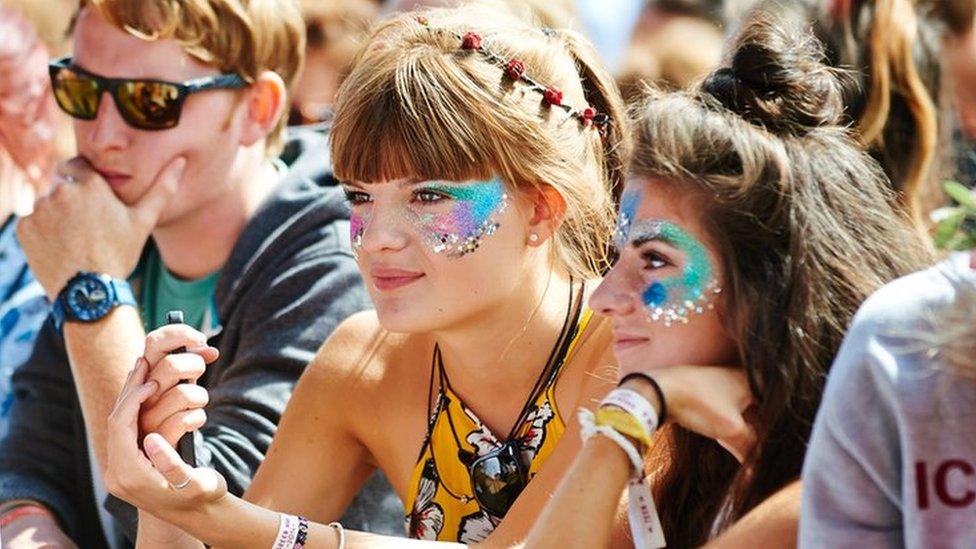

RFID wristbands for entry and payment have been used across the world for several years

The technology, which is also used in contactless bank card payments, has been widely adopted at festivals in the US and Europe, but several medium-sized UK events have also now embraced the idea, using it to eliminate cash and cards from their sites.

Steve Jenner, managing director of Playpass, which makes the wristbands, said: "Rewards could include bonus credit to be spent in the event, merchandise, access to a restricted area or the right to camp in a premium location the following year."

The wristbands will allow Bluedot visitors to check-in at stages and talks

So what do music fans make of the use of the technology? Dan Salter, editor of music magazine website Echoes and Dust, regularly attends festivals and says he broadly supports the idea, providing it does not start to interfere with the whole point of a music festival - the acts on stage.

"The danger is that you get analysis that tells you 80% of your audience went to see Band X so you should book loads of bands that sound like Band X," he says.

"Much like the Spotify algorithm that serves you a never-ending stream of stuff it thinks you will like, data can stop exposing you to that thrill of hearing something new and different."

He also says that, while not using cash at festivals is "an inherently good idea", he has "reservations" about preloading wristbands with funds, because of something called "breakage".

"That is where people load money on that they never end up redeeming. Most retailers view this as an excellent stream of effectively free money... but it is scamming the punters who are already paying an on-site premium."

RFID wristbands have virtually eradicated queues at 2000Trees, its founder says

Those are not the only concerns levelled at the contactless technology. The well-documented issues at Download in 2015, external, when a system that required online connectivity failed, have made other festivals cautious about adopting technology and experts also question the security of the system.

Mohammad Hammoudeh, an IT expert at Manchester Metropolitan University, says while the wristband itself holds very little information, it links the visitor to their registration data, which raises a number of concerns.

"You can read that tag using a standard mobile device... so somebody could duplicate it - and as it's contactless, you only need to be within a certain proximity.

"Also, the visitors are potentially being profiled and this is viewed by the security community as an invasion of privacy."

Mr Robinson says Bluedot have been "quite surprised" by the concerns raised as they "thought the audience would be slightly more with us".

The system they are using provides only "blind data", he says, which means there is "no GPRS [and] no tracking".

Festival wristbands were once simple loops of paper or material

"It's simply a device that will tell us how many people bought how many beers and at what time and such like [which is] data that a standard EPOS (electronic point of sale) system would track."

Mr Jenner says the concerns over data are understandable but unnecessary.

"It's worth noting that in the events we have worked with, none have shown an interest in using the data to see how many hot dogs Bill consumed on a Saturday."

He says they use "a global encryption standard used by the military... that has only ever been hacked or cloned in a theoretical situation, never in real life" and only use any data collected for "assisting visitors with customer service enquiries".

He adds that "under no circumstances would we ever promote, sell or support a breakage model".

"This goes completely against our ethos of putting the visitor first and would undermine acceptance of our technology."

Future uses of RFID could see visitors rewarded with prizes or access to restricted areas

Mr Robinson says Bluedot's use of contactless technology is not just about innovation, but also futureproofing.

"I was at Burning Man (in the US) and there was no cash at that - everyone just swapped things.

"It's a really interesting thing to be at a festival and suddenly find that you don't have a pocket full of change and you're not looking at notes.

"Perhaps in the future, there won't be any cash, so let's see how that feels."

Bluedot takes place between 18 and 21 July.

- Published13 June 2019

- Published12 June 2019

- Published7 June 2019

- Published24 August 2018

- Published4 July 2018

- Published2 July 2018