RSPB's Emily Williamson: The woman who saved a million birds

- Published

Emily Williamson started the Society for the Protection of Birds after an all-male organisation ignored her letters

Emily Williamson was many things in her life - a philanthropist, a bird lover, an activist and "proof that one person can make a difference".

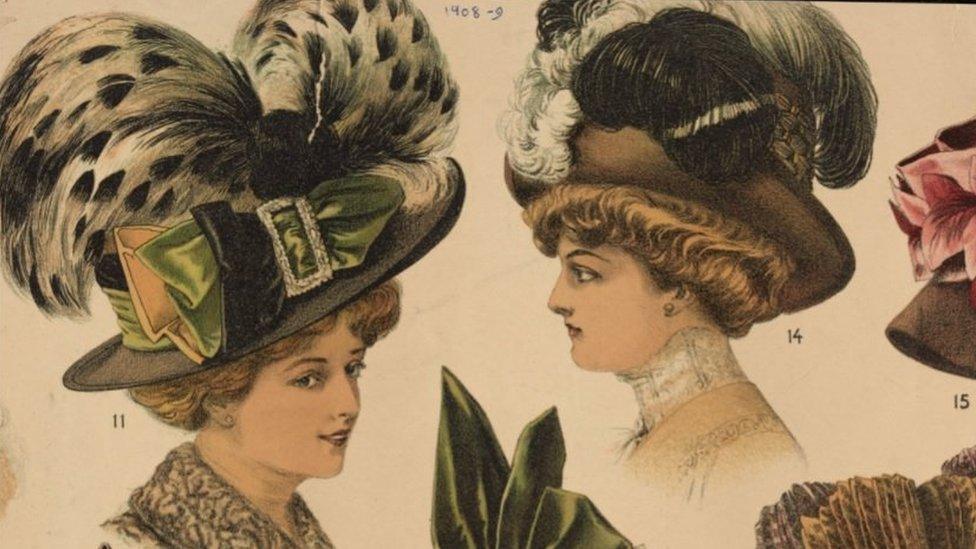

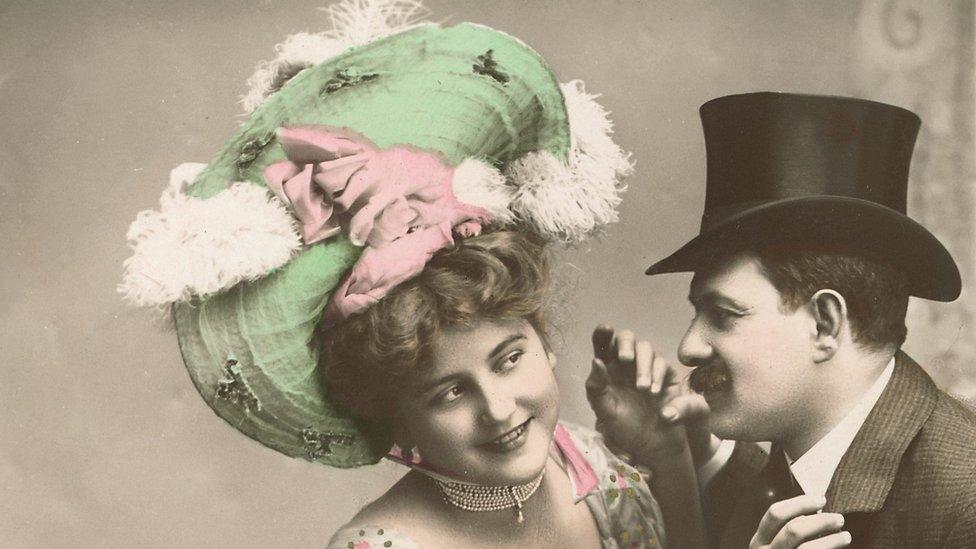

It was 1889 and a fashion craze, which involved adorning hats with not just feathers, but wings and whole birds, was showing no signs of slowing down.

It was driving some species, such as egrets, great-crested grebes and a host of beautiful birds of paradise towards extinction.

Appalled by the slaughter, the then-34-year-old invited a group of women to her home in Didsbury, on the outskirts of Manchester, to discuss how to put a stop to the plumage trade.

Mrs Williamson, who was born in Lancaster, asked those who had assembled to sign a pledge to "Wear No Feathers", a request which would have proved very unpopular at the time.

But it was from that meeting that the Society for the Protection of Birds, later known as the RSPB, would bloom and would see her pledge become law 30 years later.

On 1 July 1921, the Importation of Plumage (Prohibition) Act was passed, banning the import of exotic feathers and saving many species from extinction.

Mrs Williamson held the inaugural meeting of the society at her Didsbury home

Social historian and author Tessa Boase, whose research helped uncover the story of Mrs Williamson, says she was "a brilliant role model and proof that one person can make a difference".

She first approached the RSPB after hearing a rumour that the charity was set up by a woman but, at the time, she was told no records of its early history existed.

However, while digging around in the archives at the charity's headquarters, she found something that proved that her suspicions were correct.

"I was about to give up when I found this small square box," Ms Boase says.

"On the lid, it was written in really old Victorian handwriting - 'contraband'.

"So I prised off the lid and inside were these feathers.

"But they weren't just feathers, these were millinery adornments, dyed, curled, wired."

Hats with large exotic feathers were fashionable for women throughout the Victorian era

It was such plumage that spurred Mrs Williamson into action after her letters urging the all-male British Ornithologists' Union to take a stand were ignored.

Two years later, the society merged with another all-female group.

Led by Mrs Williamson, Eliza Phillips and Etta Lemon, and with the Duchess of Portland, Winifred Cavendish-Bentinck, as president, the society had 10,000 members by 1893.

But it would be another 28 years before it achieved its hard-fought victory on the plumage trade.

To mark the centenary of the law being passed, a statue of Mrs Williamson is to be commissioned to stand in Didsbury's Fletcher Moss Park - the gardens of her former home.

Prof Melissa Bateson says she feels "extraordinarily proud" to be one of Mrs Williamson's descendants

The Emily Williamson Statue Campaign, external began with the shared vision of Ms Boase and city councillor Andrew Simcock, who believe it could lead the way to her getting the recognition they feel she has never received.

Indeed, her story has received so little coverage that even her great-great niece was unaware of her family's connection to the RSPB until she was contacted by Ms Boase.

Newcastle University's professor of ethology Melissa Bateson, who has a specialism in starlings, says she feels "extraordinarily proud to be one of her descendants".

"It feels like an extraordinary coincidence that both my father - the eminent ethologist Professor Sir Patrick Bateson - and I made our careers studying the behavioural biology of birds without knowing about Emily and her achievements," she says.

"We clearly have birds in our blood."

The Plumage Act: From pledge to Parliament

1889 - Emily Williamson sets up the Society for the Protection of Birds in Didsbury with the aim of stopping the trade in feathers

1891 - The society amalgamates with Croydon's Fur, Fin and Feather Folk

1899 - Queen Victoria confirms an order that will see some regiments discontinue wearing plumes

1904 - The society receives royal assent, becoming The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

1908 - The Importation of Plumage (Prohibition) Bill is introduced to Parliament

1921 - The bill is passed into law, coming into effect a year later

Source: RSPB, external

Mr Simcock says the statue is about raising awareness of Mrs Williamson's "incredible story", as there is "so much to learn from Emily... that people will find empowering, particularly at a time when we face such huge environmental challenges".

Ms Boase adds that as the world is "having a bio-diversity crisis", which is seeing the skies again "emptying of birds but for very different reasons", the statue will help "crystallise the urgency and the need to fight".

She says it will also "inspire the coming generation and show women have been working in conservation for over a hundred years".

It is hoped the winning design, which will be chosen by public vote from four proposals, will be installed on 17 April 2023 on what would have been Mrs Williamson's 168th birthday.

The four designs for the statue will be officially unveiled on the centenary of the act being passed

According to the RSPB, Mrs Williamson helped saved more than a million birds.

"This year marks 100 years since the Plumage Act was passed, our first big campaigning success," says Beccy Speight, chief executive of the RSPB.

"I'm delighted there is a proposal to erect a statue of Emily Williamson in Didsbury to mark her contribution.

"I hope it will help inspire a new generation who simply want to protect nature from destruction for its own sake and for ours, as Emily, Eliza Phillips and Etta Lemon did more than a century ago."

Emily Williamson née Bateson pictured with her family

The British Ornithologists' Union, which accepted its first female members in 1910, has awarded a posthumous membership to Mrs Williamson to mark the centenary of the act she fought so hard to get passed.

"We do not know how many other women were refused membership in the previous 52 years," says the union's president Juliet Vickery.

"I hope that this posthumous membership will act as a form of recognition of them all."

Why not follow BBC North West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external? You can also send story ideas to northwest.newsonline@bbc.co.uk

Related topics

- Published1 June 2021