The weekend: The campaigning duo who helped get workers two days off

- Published

Having a couple of days off between two working weeks to do as you please is seen as a right in modern times

The Covid-19 pandemic and a new culture of flexible working has led to a change in attitudes towards the working week.

A recent trial of a four-day week has seen many of the firms involved looking to adopt it on a permanent basis and reduced hours, job shares and split shifts are now common across most industries.

What has not really altered though is the weekend, which has stayed true to its dictionary definition of being the period between two working weeks, typically regarded as a time for leisure.

For many, that means Saturday and Sunday, two days filled with rest, relaxation, recreation and maybe a little DIY.

That two-day break has just celebrated its 179th anniversary - and its existence owes much to the campaigning of two very different Greater Manchester workers.

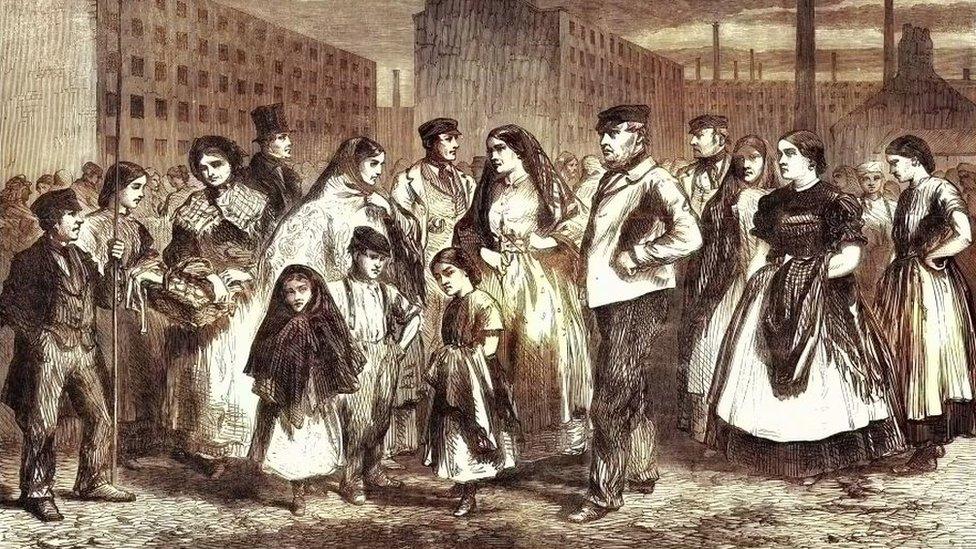

Greater Manchester's population worked long hours across a six-day week until the 1840s

In 19th Century Britain, Sundays were a holy day and nobody was expected to work, but the explosion of the Industrial Revolution made Saturdays a working day, as business owners did not want to see technology they had made a huge investment in lying idle.

That six-day week led to such a tradition of staff not clocking in on a Monday morning that it even had its own name, Saint Monday.

According to Professor Martin Hewitt, an expert in social history, Manchester's William Marsden and Salford's Robert Lowes - the great-great-grandfather of actor Sir Ian McKellen - were both fed up of the situation.

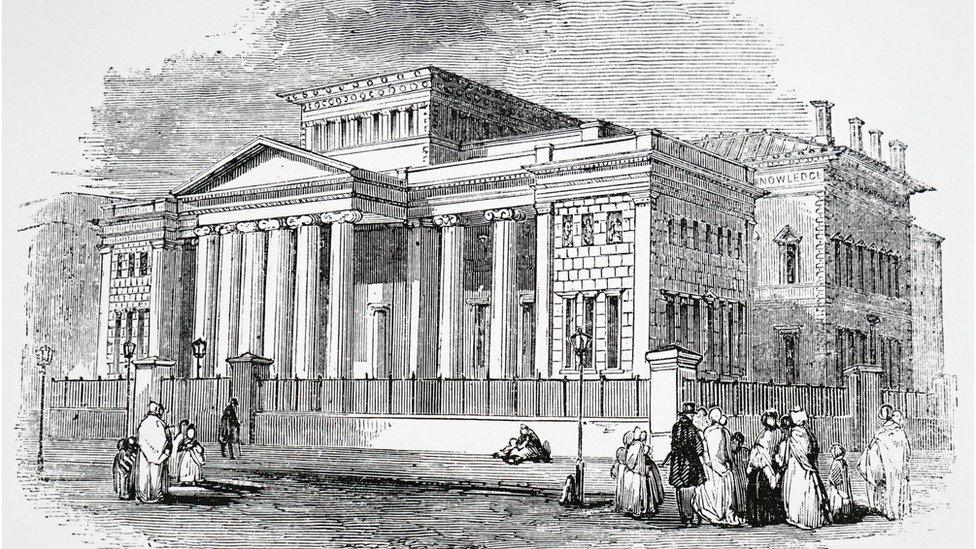

The Anglia Ruskin University historian said the pair had very different lives, but came together at Manchester Athenaeum - a society for the "advancement and diffusion of knowledge" - which met in a building which now forms part of the city's main art gallery.

He said Lowes, who was working as a clerk, "had come from Carlisle to work in Salford", while Marsden was the "son of a wealthy cotton manufacturer" who lived in Manchester, but in 1843, Lowes started to call for warehousemen to have a "half-day holiday" on Saturdays and founded a committee with Marsden to advocate for change.

Lowes and Marsden met at Manchester Athenaeum, which now forms part of the city's art gallery

The success of their campaigning can be seen at Manchester Central Library, where their signatures adorn a large scroll alongside those of more than 400 "merchant princes" who agreed to grant the new half-day holiday in September of that year.

Whether it was the diligence of the campaign or a desire to see the end of Saint Monday that swayed those business owners has been lost to history, but the idea spread to other towns and cities and, in 1850, became law as part of The Factory Act.

Though the act actually extended the work week by two hours, those hours were set within a defined time period, making family life much more manageable and freeing up Saturday afternoons for other activities.

Within the decade, the first football clubs were formed and regular concerts began to take place on Saturdays, as the day quickly became one for recreation and sport in Victorian society.

But not everyone believes Greater Manchester can take all the credit.

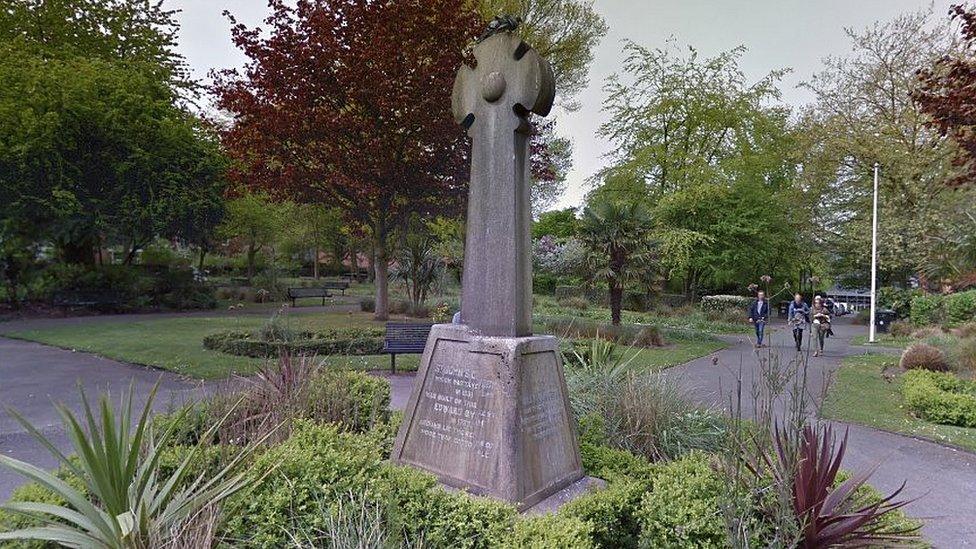

A memorial to William Marsden stands in Manchester's St John's Gardens

Professor Brad Beaven, an expert in social and cultural history, said it was not correct to say "one place is responsible for the half-day movement".

"Salford was part of a wider movement in the Manchester conurbation," he said.

"There were a lot of people doing the same thing, but Salford can claim some credit."

Prof Hewitt said it "was a local movement", but it "led people to think 'if Manchester can do it, why not us?'"

"There are newspaper reports of what Lowes and the committee achieved and it was a definite chain reaction," he said.

That query over the origin has not stopped the achievements of Lowes and Marsden being celebrated in their native cities.

Weekends have become synonymous with leisure and recreation

Salford Council recently held We Invented The Weekend, a festival celebrating "free time, quality time and me-time" based on Robert Lowes winning workers "the right to leisure time on Saturday afternoons".

Across the River Irwell in Manchester though, a memorial to William Marsden in St John's Gardens names him as the man "who originated the Saturday half holiday".

Prof Hewitt said the truth was that it may never be known which of them was the progenitor, as "we don't know a large amount about Lowes".

"He is an unknown figure apart from this one moment where he appears on the public stage," he said.

However, he added that there was no doubt that Marsden's position as chairman of the committee "gave him a certain cache, but like many organisations, it was probably Lowes as secretary who put the hard yards in".

Why not follow BBC North West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external? You can also send story ideas to northwest.newsonline@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published11 February 2022