How a Liverpool football fanzine inspired a generation

- Published

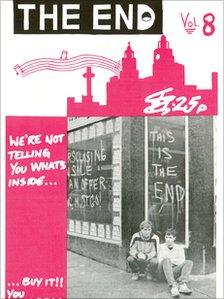

The End fanzine was a must read for football and music fans in the 1980s

Thirty years ago in Liverpool, against a backdrop of factory closures, riots and rising unemployment, there was a thriving underground press.

Before instant messaging and social media websites, a hand-drawn fanzine appeared on the city streets.

Passed between friends in music shops and at football matches, the pocket sized magazine was full of street attitude, humour and graphics.

Written and published by young men, for young men, The End became a template for the lads' mags of the future.

Its final edition came out in 1988 - and for many its wit, zest and style has been forgotten.

But the fanzine is now set for a new lease of life as publisher Sabotage Times is set to release an anthology of The End's 20 editions.

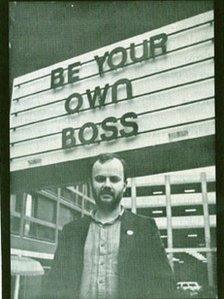

The End co-founder Peter Hooton, who went on to become lead singer of The Farm, said: "It was based on observations of working class life. It's like a diary of underground Liverpool in the 1980s."

The magazine, famed for inventing the Ins and Outs section on current trends - now common in newspaper columns - centred on music, football and fashion.

But this was a group of lads from Liverpool who did not take themselves too seriously. Cartoons and characters were based on familiar faces of the football and music scene.

Peter Hooton went on to be front man of the band The Farm

For instance the hygiene of hot-dog sellers near football grounds was mercilessly ridiculed, along with woollen bobble hat wearers.

Mr Hooton said: "We attacked everything that moved.

"Anything that was deemed fashionable by people we'd immediately put it in the Out column."

The first run of 500 copies cost £90 to produce and was sold for 20p but Mr Hooton says it was never about the money.

"We tried to give a platform to people who didn't really have access to the media.

"It was before the days of Twitter and Facebook. Everyone is doing it now, everyone is writing. In those days to get stuff in print was a lot more difficult.

"It was an opportunity for people to express themselves. It gave people a voice."

As word spread across the country, the magazine got a surprise following in West Yorkshire.

Leeds football supporter James Brown, who went on to be the editor of men's magazine Loaded, became a fan and the banter from the football terraces crossed into the letters pages.

He said: "To those of us looking into Liverpool through The End, it seemed a world of fashion-obsessed lunatics with their own language, heroes and priorities.

"The magazine's correspondents often had a fierce superiority complex about how behind the times anyone who didn't live within a mile or two of Liverpool's city centre was.

"Wearing the wrong trainers, shirts or haircuts could brand you a 'wool' (a derogatory term for people from outside Liverpool) and as for those of us who lived on the wrong side of the Pennines, we were portrayed as still dressing in Oxford bags, star jumpers and stack heels.

DJ John Peel appeared on the cover of The End Volume 5

"It was impossible to read The End without laughing. The humour and simple presentation meant you read every word of the mag."

Even DJ John Peel was an avid reader.

"We wrote scathing letters to John in the early days criticising his music policy, which was sacrilege," Mr Hooton continued.

"No one ever did that. He said that jumped out at him. We did an interview with him and he always championed the magazine from that day on."

The small production team went on to create 20 editions over seven years and featured interviews with musicians including The Clash, The Mighty Wah and The Teardrop Explodes.

"We had a great time doing it," Mr Hooton added.

"We realised you could get an interview with anyone. All you had to do was go to the sound check of a group, there was no security, and they'd just give you an interview to get rid of you.

"There is a lot of people saying the 80s was a terrible time but it was a very creative time.

"A lot of groups came out, a lot of writing and a lot of plays came out of Liverpool out of that depression and unemployment and the social problems a lot of creativity came out of it.

"Revamping The End it is just reminding people that it wasn't all as bad as it was made out to be."