The fall and rise of Liverpool docks

- Published

The giant Megamax cranes loom over boats on the River Mersey at the Liverpool2 terminal

Liverpool docks were once filled with the sound of horses' hooves, the commotion of emigrants leaving for a new life and the din of stevedores loading heavy goods on to vessels bound for the Atlantic. Following a rapid decline in the 20th Century, it is now hoped the docks are witnessing a renaissance with the opening of a vast new container terminal.

The construction of a huge new deep-water shipping dock dubbed Liverpool2, which can cater for a new breed of giant container ships, is seen as a new start for the city.

It forms part of the new SuperPort project extending across the north-west of England, created to revive and boost the region's industry.

Liverpool's history is bound to the tides of transatlantic transportation: from the city that grew powerful and prosperous from the slave trade, to the mass migration of people seeking a better life in the new world and the age of luxury cruises.

As a gateway for mass emigration between 1830 and 1930, nine million people sailed from Liverpool, most bound for North America, Australia and New Zealand.

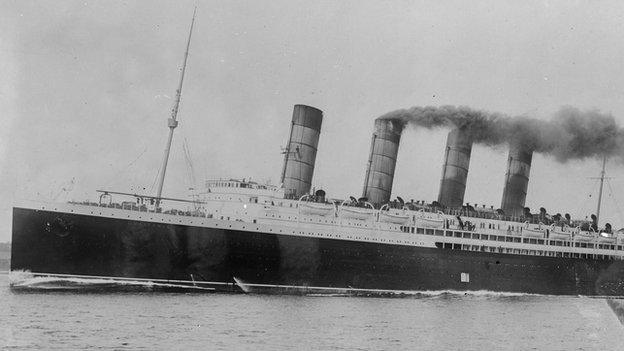

But when the trend dwindled after World War One and Cunard's luxury liner services moved to Southampton in 1919, the port's decline seemed assured.

Despite these setbacks Liverpool retained a cargo industry and earlier this month, the arrival of huge new cranes from China signalled a new chapter in the port's long history.

The cranes make ordinary ships look tiny

Bigger docks

Sarah Starkey, curator of maritime and slavery archives at the Merseyside Maritime Museum, external, said its new exhibition - On the Waterfront - which opens on 25 November, charts the port of Liverpool's changing economic fortunes down the centuries.

Because tankers are getting larger, Ms Starkey said Liverpool has "had to constantly build bigger docks and are still doing today".

She said Albert Dock, constructed in 1846, was outgrown by the ships using it within a few decades "although the warehouses remained profitable for years".

She said although Liverpool port's decline was "undeniable", large amounts of cargo were still moved in big container ships which were less labour-intensive.

People emigrate from Liverpool docks in 1913 for a new life in Australia

Liverpool's super port

The port's capacity will increase from 1.5 million containers a year to 2 million

The Liverpool2 cranes will lift containers off and on to ships and allow vessels carrying up to 13,500 containers to call at the port

The Mersey approach channel is being deepened to 16m (52ft) to accommodate the vast ships arriving from the newly widened Panama Canal

Peel Ports has previously said 5,000 jobs will be created as a result of the expansion

The port's current capacity is currently limited to ships with fewer than 3,500 containers

At 90m (300ft), the Megamax cranes are taller than the city's famous Liver Building

The redevelopment of the Albert Dock in the 1980s was the brainchild of the then Secretary of State for the Environment, Michael Heseltine, who helped breathe new life into the rundown warehouses which are now an entertainment and shopping hub and home to the Tate Liverpool, external gallery.

Liverpool also saw the return of cruise liners, which traditionally sailed from Southampton, and its leaders were engaged in a verbal spat.

'Completely redundant'

Freelance maritime writer Peter Elson said: "The shipping industry has not died in Liverpool but as the ships have got bigger, the port has had to move further to the north of the city."

This is partly because of the River Mersey's large tidal range and fast-flowing water.

He said the south docks were now "completely redundant" with only motor cruisers and yachts berthed there.

With the widening of the Panama Canal, larger container ships from the Far East can now reach Liverpool much more easily, he said.

Although there is some scepticism, he warned that if no action was taken Liverpool could "tumble down the second and third division" in maritime significance.

The first known painting of Liverpool as a port in 1680

Albert Dock now only provides moorings for leisure boats

Albert Dock, in the foreground, before it was developed in the 1980s

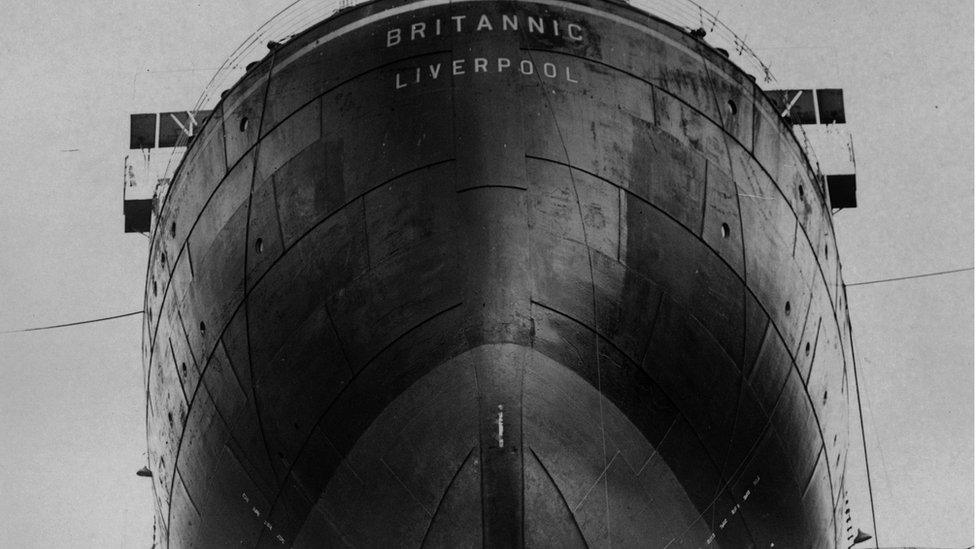

The Cunard White Star liner in Liverpool in December 1938

The history of Liverpool's dock

1715 The Old Dock - the first commercial wet dock - opens in Liverpool

1765 Three Canning Graving Docks are built to service ships used by merchants involved in the transatlantic slave trade

1807 Slavery is abolished, ending the trade

1826 The Old Dock is finally too small and shallow and is filled in and Customs House is built on the site

1846 Prince Albert opens the eponymous dock in July

1878 The Hydraulic Pumping Station is added to the dock to provide power for gates, bridges and capstan access

1911 The Liver Building - the first of Liverpool waterfront's Three Graces is built

1927 Gladstone Dock is completed which is still in use

1971 Albert Dock is used for the last time

1984 The first phase of the redeveloped Albert Dock opens

'Magic bullet'

Stuart Wood, a retired Pilot Ship pilot, who worked for the Port of Liverpool and retired six years ago, said when he joined in 1960 "the glory days were already threadbare".

He said: "Then the container came along and British shipping wasn't ready for it." Mr Wood said other countries took advantage of British inertia and some companies "faded away".

Mr Wood described container ships as a "magic bullet" which at the same time killed the shipping industry in Liverpool.

With the Liverpool2 super port around the corner, it is hoped it will once again witness a revival.

- Published27 March 2015

- Published28 May 2013

- Published19 February 2013

- Published13 November 2012

- Published1 August 2012

- Published5 March 2012

- Published24 January 2012

- Published7 June 2011

- Published10 September 2013