Hillsborough trial: Fans 'failed by match chief'

- Published

David Duckenfield (left) and Graham Mackrell arrive at Preston Crown Court

Match commander David Duckenfield's "extraordinarily bad" failures led to the deaths of 96 "wholly innocent" fans at Hillsborough, a court has heard.

The ex-policeman did not quickly take measures to free Liverpool supporters trapped in the fatal crush at the 1989 FA Cup semi-final, jurors were told.

Prosecutors said his actions "contributed substantially" to the "tragic and unnecessary" loss of life.

Mr Duckenfield, 74, denies the gross negligence manslaughter of 95 fans.

Ex-Sheffield Wednesday club secretary Graham Mackrell, 69, who is on trial alongside the former South Yorkshire Police chief superintendent, denies safety breaches.

Opening the case at Preston Crown Court, prosecutor Richard Matthews QC said each of those who died did so as a result of "the wholly innocent activity of attending a football match".

On the day of the disaster, he said, a capacity crowd of 50,000 had been expected at the game between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest.

Of those, jurors heard, 24,000 Reds supporters were directed to the Leppings Lane end of the Sheffield Wednesday ground.

'Resuscitation delayed'

Pressure to get through the turnstiles "almost inevitably" built up outside the stadium before kick-off, Mr Matthews said.

Under Mr Duckenfield's direction, the court heard, an exit gate - known as Gate C - was opened to alleviate the crush.

Once inside the ground, Mr Matthews said, the crowd was met with a sign leading them towards two fenced pens on the terrace which were already full.

"David Duckenfield gave no thought to the inevitable consequence of the flood of people through Gate C," Mr Matthews said.

"Nor did he make any attempt to even monitor what was occurring, let alone avert the tragedy".

Mr Duckenfield, of Ferndown in Dorset, would have had "ultimate responsibility" for the police operation as match commander, Mr Matthews told jurors.

But as the disaster unfolded, the court was told, Mr Duckenfield failed to quickly declare a major incident or enact emergency measures to free trapped supporters.

The senior officer also failed to provide "emergency medical attention, particularly attempts at resuscitation", in a timely fashion, Mr Matthews said.

"It is the prosecution's case that David Duckenfield's failures to discharge this personal responsibility were extraordinarily bad and contributed substantially to the deaths of each of those 96 people who so tragically and unnecessarily lost their lives," he added.

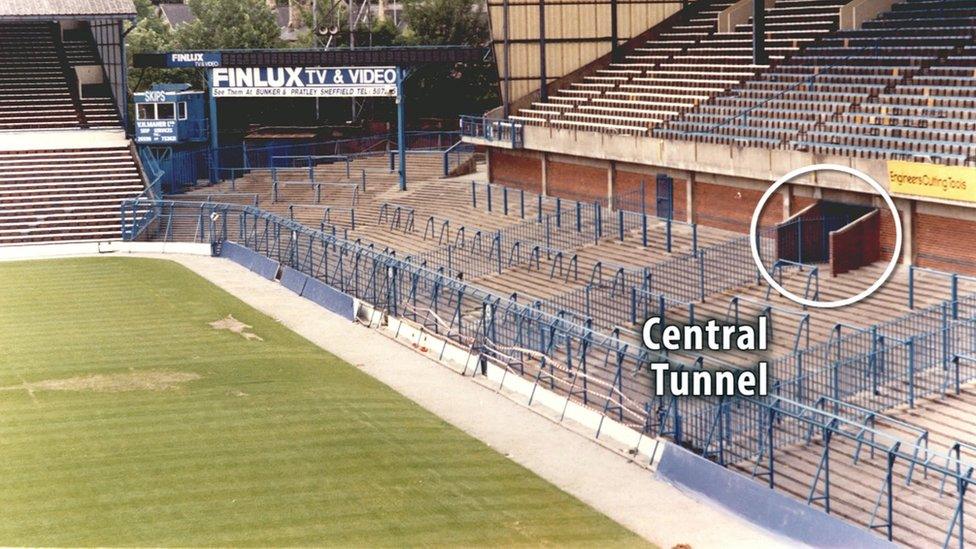

Fans entered pens three and four through the central tunnel after Gate C was opened

What happened at Hillsborough?

Outlining the prosecution's case, Mr Matthews said:

Pressure built up outside turnstiles at the Leppings Lane end of the stadium, where 24,000 Liverpool fans were to be directed

An exit gate - known as Gate C - was opened after requests by Mr Duckenfield to do something to alleviate the crush outside

Once inside the stadium, fans were met by a sign which led to pens three and four of the terrace - which were beneath the police control box

Mr Duckenfield did nothing to monitor the capacity of the pens, which were already packed by the time the gate was opened

He further failed to redirect the crowd to other, less crowded pens and control access to the tunnel to "prevent the inevitable crush of fans effectively carried away down the slope of the tunnel".

"Much about the Hillsborough disaster was extraordinary, not least the appalling scale of the loss of life, the scale of tragedy and the scale of those who failed to discharge their responsibilities with appropriate care," Mr Matthews said.

"Undoubtedly, each of the deceased has been failed by many, in many ways and over a protracted period; before, during and even after this disaster," he said.

"Each died as a result of the extraordinarily bad failures by David Duckenfield in the care he took to discharge his personal responsibility on that fateful day."

'No means of escape'

Jurors were shown a computer-generated video of key areas of the stadium

The jury was shown photos, video footage and plans of the stadium, which was the third largest club football ground in England in 1989.

One clip was a computer-generated recreation of Hillsborough as it would have looked at the time.

Jurors were shown a "walkthrough" of the Leppings Lane end of the stadium up to pens three and four where the fatal crush occurred.

Mr Matthews explained the turnstile configuration and showed pictures of the possible routes for fans to take once inside.

He said in the event of a crush in pens three and four there was no means of escape, other than the way spectators had come in.

"The way in is through the tunnel. In a crush, the pressure is coming from that direction and the only way out is back against the pressure of that crush," he said.

Jurors were told second defendant Mr Mackrell was the Sheffield Wednesday safety officer responsible for ensuring the club followed Home Office guidance.

Mr Matthews said the club breached the conditions of its safety certificate by failing to agree methods of entry into the stadium with police before the semi-final.

Mr Mackrell, of Stocking Pelham in Hertfordshire, committed an offence by "by agreeing to, or at the very least turning a blind eye to," the breach, he said.

'Shrugged responsibility'

Mackrell, who joined the club in 1986, is also charged with failing to take reasonable care of the health and safety of others, in respect of the arrangements for admission to the ground and the drawing-up of contingency plans.

This concerned ensuring turnstiles were sufficient to admit fans at a rate whereby no unduly large crowds would be waiting outside and planning how to cope in the event that entrances proved insufficient to stop such a crowd from gathering, he said.

Mr Matthews said: "It is the prosecution's case that Mr Mackrell effectively shrugged off all responsibility for these important aspects of the role he had taken on as safety officer."

The court was adjourned until Wednesday.

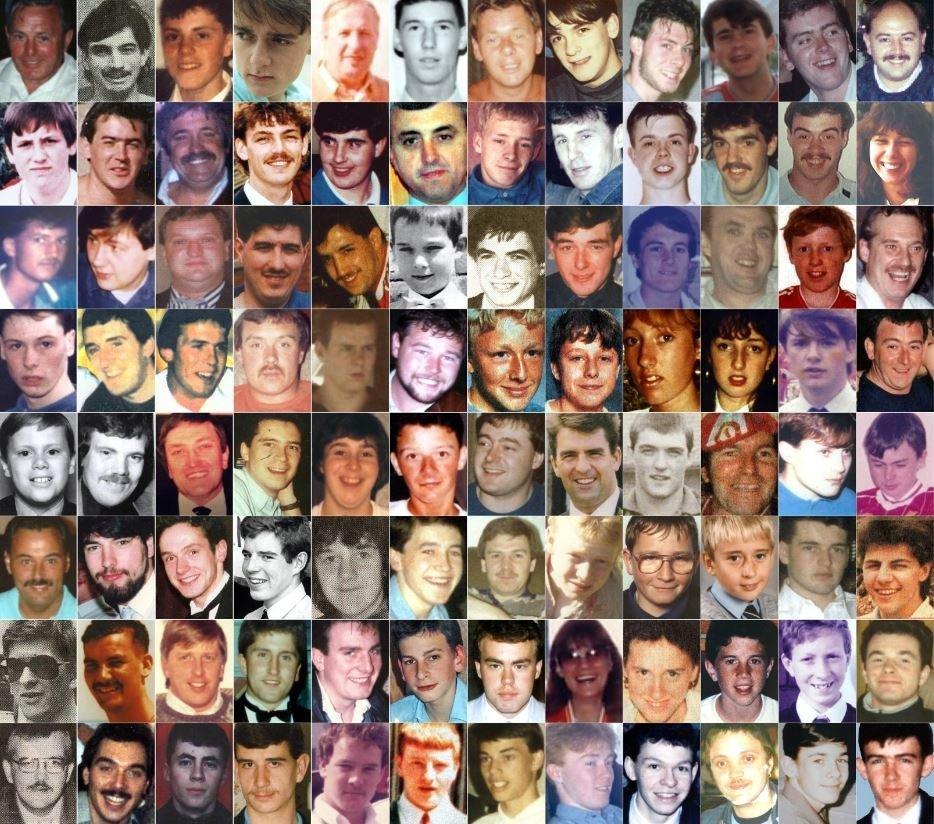

The 96 victims

The 96 people who lost their lives in the Hillsborough disaster

Jurors have been told 96 fans were killed as a result of a crush in pens at the Leppings Lane end of the ground.

Of those, 94 died on the same day.

The youngest of the victims had been 10-year-old Jon-Paul Gilhooley.

Lee Nicol, 14, died two days later and Tony Bland, who suffered "terrible brain damage" was in a permanent vegetative state until his death in March 1993, jurors heard.

Under the law at the time, there can be no prosecution for the death of Mr Bland, as he died more than a year and a day after his injuries were caused.

- Published14 January 2019