The slavers and abolitionists on Liverpool's streets

- Published

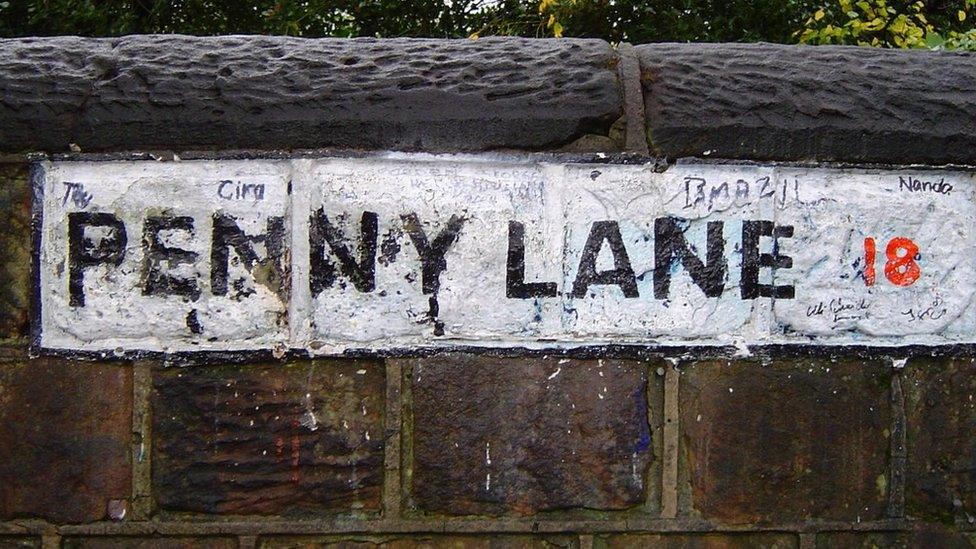

The names of streets associated with slavery hang in Liverpool Slavery Museum

Stick a pin in a map of Liverpool and chances are you will skewer a name linked to slavery.

Between 1700 and 1820, many of the city's bigwigs were involved in the slave trade, exploiting the Triangular Trade - the movement of goods and slaves between Britain, Africa and the Caribbean - to finance their political, personal and social aspirations.

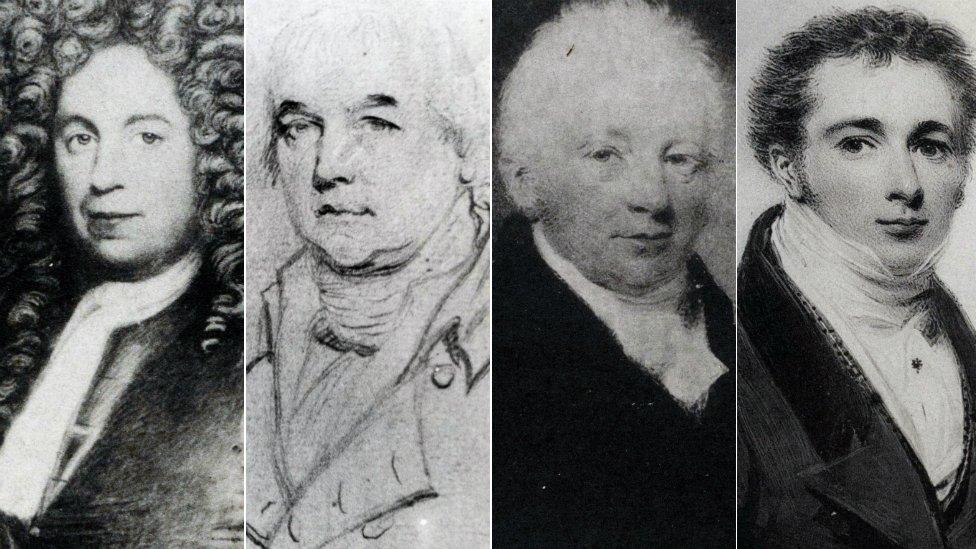

At least 25 of the period's lord mayors were slave owners or traders and many of them have been immortalised in the likes of Tarleton, Cunliffe and Gildart streets.

That uncomfortable fact has led the city's current mayor Joe Anderson to propose introducing plaques to give an "honest account" of their links to the slave trade.

Penny Lane - made famous by The Beatles - is thought to have been named after slave trader James Penny

Dr Richard Benjamin, the head of Liverpool's International Slavery Museum, said that was a "welcome proposal", though he would also like a "full renaming" of streets to be considered.

"I don't think it's a bad move to rename streets for people who you would want to represent your city," he said.

"That said, I also understand the argument for placing street names in context.

"A street like Bold Street, which is very bohemian today, is named after a slave trader, Jonas Bold. It would make a statement if a thoroughfare such as that was on the list."

Bold Street is one of the more prominent examples, but many more roads in the city are named after slave owners, transporters or merchants - while a handful also celebrate those who fought against the trade.

Sir Thomas Street

Sir Thomas Johnson was the part-owner of one of the first recorded slave ships to sail from Liverpool and is known as the founder of the modern city.

Born in the city in 1664, Sir Thomas rose to prominence on the back of his father's fortune and represented Liverpool in Parliament in the early 1700s, pushing for Crown recognition of the city and the construction of the city's docks, which served his own interests, as he traded in sugar and tobacco, as well as slaves.

But, while the dock would lead to a huge increase in the city's trading, Sir Thomas lost his fortune in the South Sea Bubble crash in the 1720s and lived out his final years on a small pension.

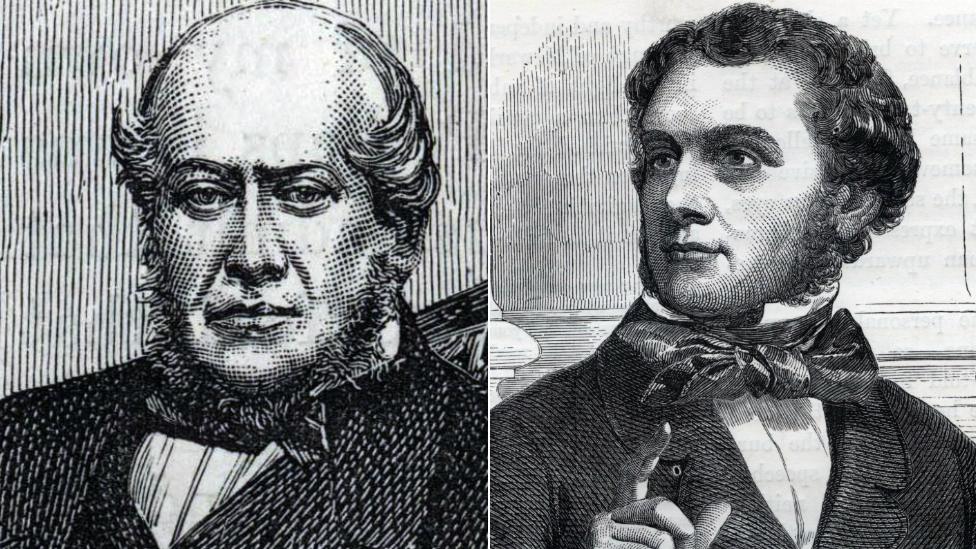

Gladstone Road

The wealth Sir John Gladstone accrued enabled him to send his son William to Eton, which paved the way for his career as prime minister

Sir John Gladstone moved to Liverpool in 1786 to exploit the opportunities for financial gain in North America and the Caribbean, seeing his fortune increase from £4.3m to £51m in modern terms across the next three decades.

That wealth allowed Sir John to send his son William to Eton for schooling and the boy would eventually serve four terms as prime minister.

He used his maiden speech in the House of Commons to support his father's interests, arguing against abolition, and while that argument failed, his finances did not - when slavery was abolished in the 1830s, the Gladstones received more than £90,000, about £9.5m in today's terms, as compensation for the slaves they were forced to free.

Such has been the controversy around the family's name that in 2017, students campaigned to have his name removed from a University of Liverpool building.

Parr Street

Thomas Parr, whose house still stands on the corner of Parr Street and Colquitt Street, was the owner of a massive slave ship that was named after him.

Housing 700 berths for slaves, the Parr went down in 1798, having reportedly exploded off the west coast of Africa - an indication it was carrying gunpowder to exchange for slaves.

Behind his house stood his warehouse, which is now a Grade II-listed building and has been shown to have housed iron goods, which were also shipped to Africa by Parr to trade for slaves.

Having made his fortune by the turn of the century, Parr moved from Liverpool to Lythwood Hall in Shropshire and in 1840, he met the scientist Charles Darwin, who would later describe him as "an old, miserly squire".

Roscoe Street

Thomas Parr's move freed up his Liverpool house, which in 1822 became the home for the Liverpool Royal Institution - an establishment founded for the "promotion of literature, science and the arts".

Many of those involved in it were slave traders or owners but it was led by abolitionist William Roscoe, who was also an attorney, author, art collector, banker, botanist, poet and politician.

After being elected as an MP in 1806, Roscoe backed William Wilberforce's motion to end British involvement in the slave trade.

His stance was not without personal cost, as he was accosted by pro-slavery activists on his return to Liverpool and later saw one of his supporters murdered in a related brawl but such was the eventual civic pride in him, his name was also given to Roscoe Lane and Roscoe Gardens in the city.

Earle Street

The rise and wealth of the Earle family is inextricably linked to slavery, as generations were involved in the trading and ownership of so-called human cargo.

John Earle masterminded the family's rise, trading in tobacco, sugar and iron goods in the early 1700s, before his sons took over - with William, his youngest, captaining a slave ship and part-owning other slaving vessels.

Over the following decades, their amassed wealth, earned from slavery-supported industries and plantations, saw the family become part of the establishment, with William's son Thomas building Spekeland House, close to what would become Earle Road, and his grandson, Sir Hardman Earle, lending his name to the newly-established settlement of Earlestown, near Newton-le-Willows.

Source: Historic England, Liverpool's International Slavery Museum

- Published10 January 2020