Evidence of human life found under North Sea off Cromer

- Published

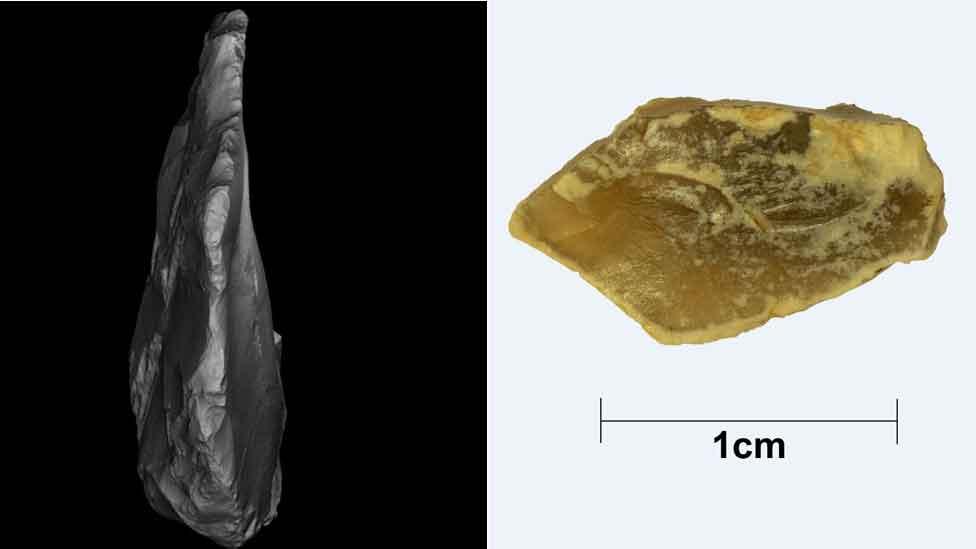

Two views of a hammerstone flint found on the seabed 25 miles off the Norfolk coast

Archaeologists have found the first signs of two potential prehistoric settlements under the North Sea.

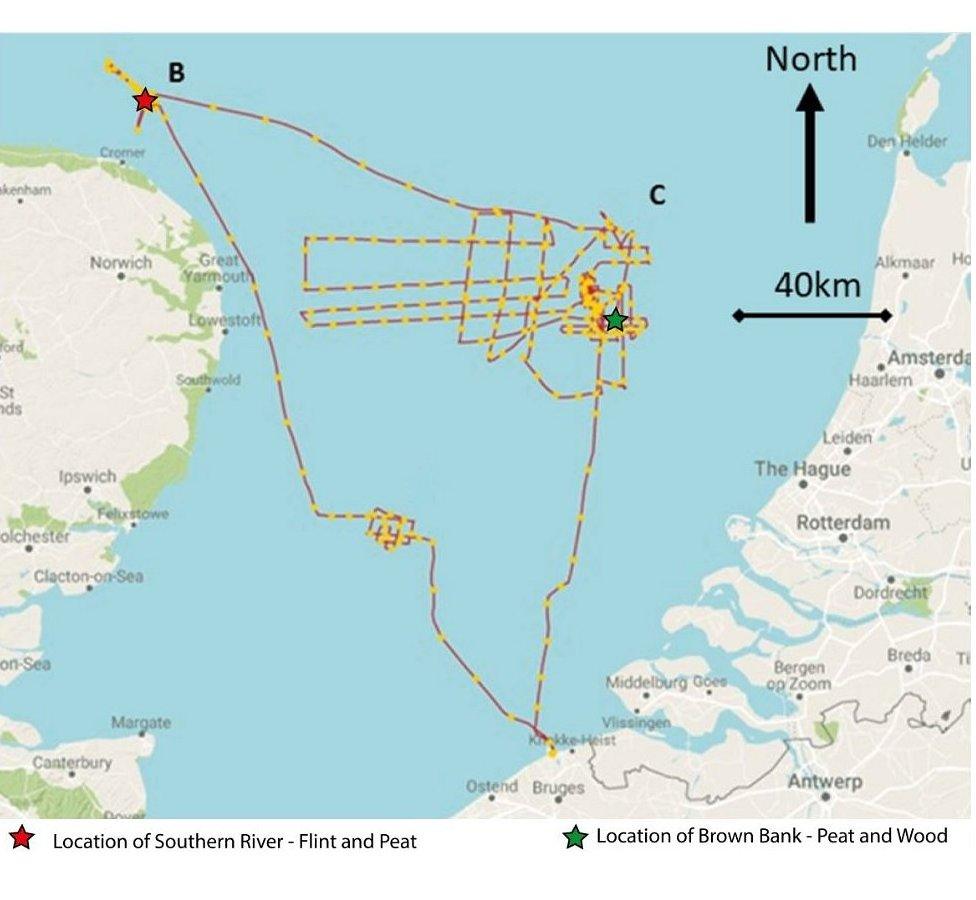

Teams from universities in England and Belgium discovered evidence of woodland and flint in the seabed 25 miles off the coast of Cromer, Norfolk.

The researchers used the latest sound wave technology to scan the seabed in May.

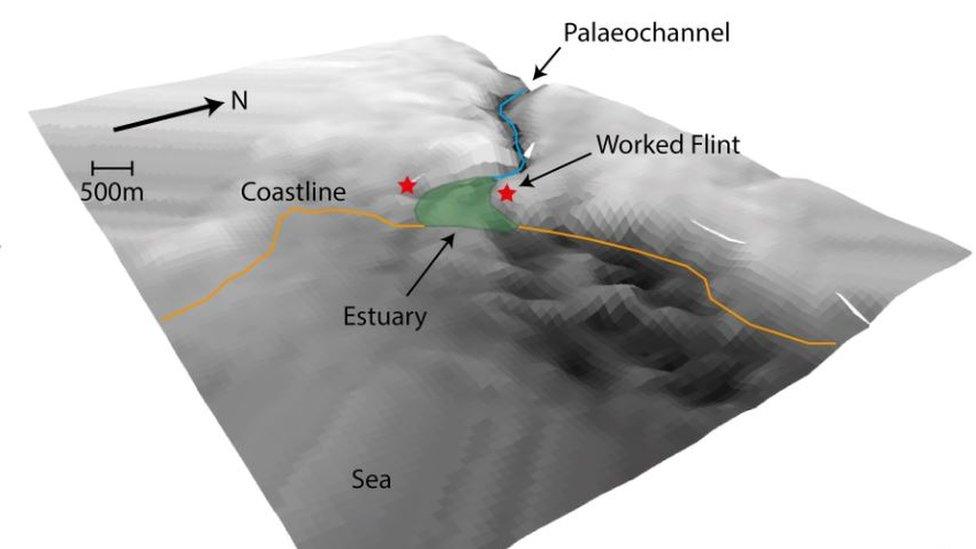

They found evidence of human activity in two places, including an ancient submerged river estuary.

The project was led by scientists from the University of Bradford, and Ghent University.

Seismic mapping scientist Dr Simon Fitch, from the University of Bradford, said: it was "the start of a whole new discovery in archaeological science".

He said it was the first time artefacts from 8,000 years ago had been discovered so far out to sea.

The modelling led the team to pinpoint where the likelihood of past human activity could be

The teams have spent the past two years recreating and modelling the drowned landscape of Doggerland using data provided by oil, gas, wind and coal industries, before the successful exploration last month.

Doggerland was drowned by seas some 8,000 years ago and is an area that stretches from the east of England to the Netherlands and Denmark.

Dr Fitch said using the latest technologies the researchers managed to obtain high resolution images of the deposits beneath the seabed for the first time.

The team found evidence of a well-preserved Middle Stone Age land surface near Brown Bank where several large samples of peat and ancient wood were recovered.

Dr Fitch said this evidence "strongly suggests" a prehistoric woodland once stood in the area before it was flooded.

A survey off the coast of Cromer targeted a large ancient river system, dubbed Southern River by the scientists, and led to the discovery of flint.

Doggerland, mapped in yellow lines, was searched for evidence of prehistoric communities

Two pieces of stone flint were recovered in seabed sediment samples taken from a depth of 32m (104 ft).

Dr Fitch said the smaller piece was possibly the waste product of stone tool making but the second larger piece, appeared to have broken from the edge of a hammerstone, used to make a variety of other flint tools.

"We're fairly confident especially given where it is in the landscape and what we know about prehistoric communities that this is a key place where people would have wanted to live," he added.

"These are people who were just like us, who around that time built some of the first houses around Britain."

Dr Fitch said the findings provided archaeologists with "for the first time, prospect for evidence of human occupation in the deeper waters of the North Sea with some certainty of success".

Before global warming at the end of the last Ice Age Britain was physically attached, external to mainland Europe.

Two views of a piece of flint found in the sea bed near an ancient estuary dubbed Southern River by scientists

- Published27 November 2010