Barry Bridges: 'Caring for children with disabilities beats playing for England'

- Published

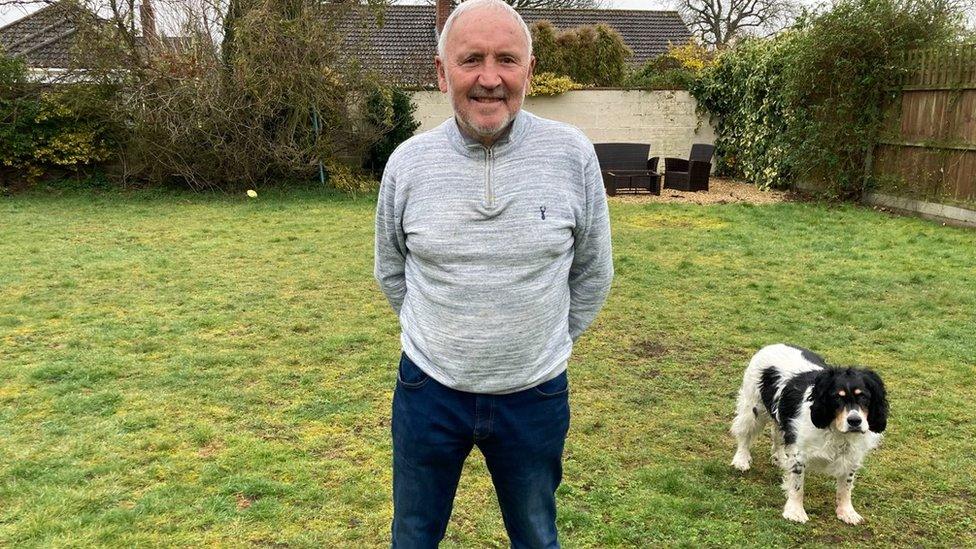

Barry Bridges in the garden of his home in Norfolk with his dog, Roger

Former footballer Barry Bridges scored for England and played as a forward for teams including Chelsea, Birmingham City and QPR. However, although he is proud of his achievements on the pitch, it is not the part of his life which has delivered the most satisfaction.

"I don't underestimate what I've done as a footballer," says Mr Bridges, who lives in Norfolk.

"But this is just as important," he says, describing his post-retirement role providing respite care to parents of children with disabilities.

"It's the greatest thing I've ever done."

I know first hand just what it means to be on the receiving end of the kind of respite offered by Barry and his wife Megan - because, for a five year period, they cared for our son William, who has epilepsy, autism and severe learning difficulties.

How did a former professional footballer end up providing such support to parents?

'At Chelsea, the maximum wage was £20 a week'

Barry and his wife Megan look after disabled children at their home to give families a break.

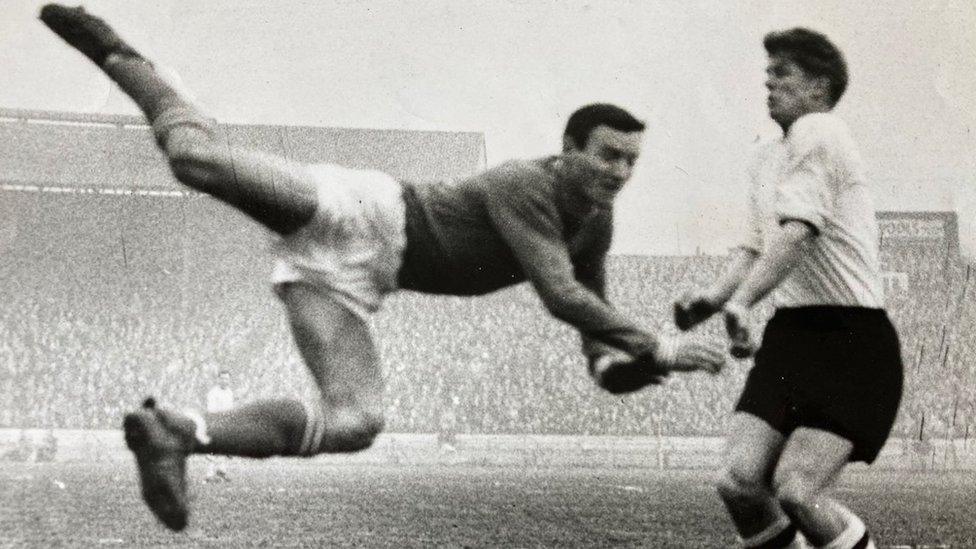

Pay for the top footballers of Barry's generation was modest.

"We didn't get any money," he says.

"When I first played for Chelsea there was a maximum wage, it was £20 per week" he says.

The paucity of pay meant players nearly always needed to start a new career rather than retire to a life of luxury.

Barry's best friend Bobby Tambling, for example, went into the building trade.

Another friend, the former England manager Terry Venables co-wrote a string of novels before going into football management.

Now aged 82, Barry took on a milk round after leaving football. He later went into business as a news agent.

"Can you imagine Harry Kane retiring from football and delivering milk at 04:00 the morning?" he asks.

'It is quite intense'

Barry and Megan provided respite care for the author's son, William

Barry and Megan first became involved in caring about 20 years ago.

At the time, one of their daughters, who worked at a special school, started caring for children with disabilities.

Barry and Megan helped out here and there but eventually decided they wanted to take on the responsibilities themselves.

The couple went on a fostering course and went through intensive screening process before they were able to care for children at their home.

"You do a lot of training," says Megan. "You go through a process of being approved as a foster carer so it is quite intense and you have to go in front of panels to be approved."

Most of the children the Bridges care for come for short breaks, usually to give their parents a rest.

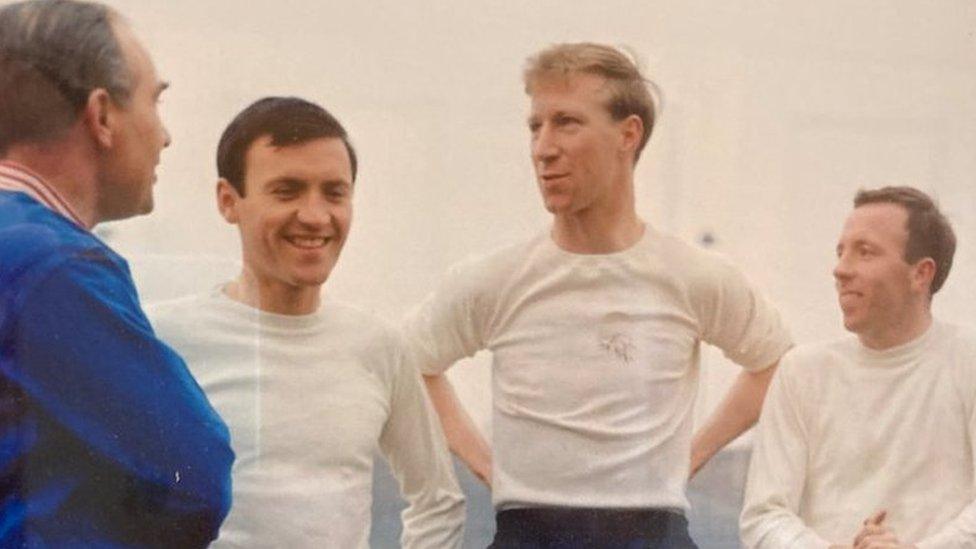

Barry Bridges earned four full England caps and made 176 appearances for Chelsea between 1958 and 1966.

Sometimes the couple will care for young people who have a difficult home life.

Some of these children will stay with the couple at weekends for a number of years, depending on the package agreed with Norfolk County Council.

What does a typical day with the Bridges look like?

"It would it be activities at the table doing drawing and puzzles and different things." says Megan.

"Then lunch and normally in the afternoon we would take them out bowling or to the cinema or take them out for a drive. Then it is back home for dinner, bath and bed."

This respite provides parents with a break, enabling them to snatch a few days of normalcy without having to attend to a child whose complex needs will often require constant vigilance and interventions.

Deep connections are formed between the Bridges, the children they care for and the families receiving respite.

"We've had a young man who is now 20 years old," says Megan. "We've had him since he was four and we've got another young girl who we had since she was four and she's now sixteen.

"So, yes, we do develop long term relationships and they continue after the care package ends sometimes.

"They become part of your life."

Giving parents a break

According to the Disabled Children's Partnership respite - also known as short breaks - provides a way for parents of children with disabilities to get a rest from their caring responsibilities.

Local authorities are legally required to provide this service.

Research by the charity Contact, external in 2017 showed almost a quarter (24%) of parents of children with disabilities provided more than 100 hours of caring every week.

More than half (56%) were provided more than 35 hours.

Parents were also more likely than other carers to report a poor quality of life "with restricted social and life choices".

A spokesman for the DCP said: "Many families find it difficult or impossible to access the support they need and the majority of local authorities have cut their spending on short breaks."

'One lad, he's football crazy'

A picture in Barry's hallway shows him (second left) at an England training session with Sir Alf Ramsey, Jack Charlton and Nobby Stiles

And yes, if asked Barry will kick a football around with a child in his care.

"I've got one lad, he's football crazy," he says.

This young man plays for a side connected to Norwich City's Community Sports Foundation, external, an organisation Barry praises highly for the way it supports players with disabilities.

A lot of the major clubs have similar set-ups he says, adding: "You have a lot of professional clubs who get blamed for big money and things like that but people don't realise how much Norwich City and all the clubs do for these kids."

During our conversation, Barry produces a wadge of worn pages containing thousands of signatures from Chelsea supporters.

This, it turns out, was a petition demanding Barry stay at the club when manager Tommy Docherty wanted to sell him

He is a man who knows the ecstasy of scoring at the top flight and the adulation of fans.

Barry Bridges (left) in his prime as a Chelsea player during a match against against Huddersfield in 1964

But caring, he says, is the best thing he has ever done.

"I do appreciate my career. But what we've done together with these kids is unbelievable.

"I've always said to Megan that if I hadn't been a footballer, if I had a life again and I knew I couldn't be a footballer, I'd have gone full time into this respite thing dealing with these kids because I love it."

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external. If you have a story suggestion email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk