The shoes hidden in homes to ward off evil

- Published

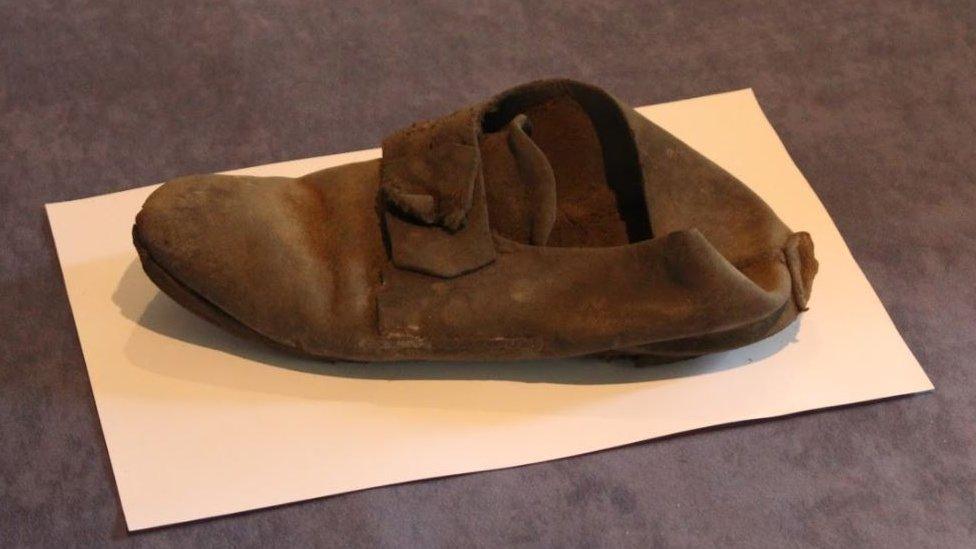

Pairs of shoes, like these 1840s Blucher ankle boots found in a military prison in Northamptonshire, are rare finds

Thousands of buildings in the British Isles are believed to have shoes hidden within their walls. But why did superstitious builders and homeowners believe in such a mysterious tradition?

In 2014, Laura Potts was renovating her Georgian home in a village near Norwich when she made a visit to check on the builders' progress.

"It was late afternoon, that golden hour with the sun coming in through the glass," she said.

"And I looked over and saw something on the windowsill.

"It was a shoe."

Most finds date to the 18th and 19th Century, like the shoe found in the home of Laura Potts

The small, patched and worn woman's shoe had been discovered in the pocket of a chimney wall by a plumber, who had left it out for her to see.

Feeling "very excited", Ms Potts posted a photograph of the find on the intranet at work. As a media relations manager at the University of East Anglia, she was in the right place.

History professor Malcolm Gaskill replied with a theory - the shoe had probably been left there as a decoy to lure "witches" away from the home.

"In the early modern period, people also believed in demons, ghosts, elves, goblins - but witches were the most frightening because they were in human form," he said.

Worst still, they were "usually someone living close by - your neighbour".

The solution, he explained, was "everyone" protected their homes against evil by hiding the shoes - like an early form of home insurance.

His "best guess" for why shoes were chosen is they mould to shape, so might be considered "imprinted" with the "character and essence" of the wearer.

Alison Norman's shoe, found in a chimney, came with a large lump of mud and grass as if had been taken off a child's foot just before concealment

Portals - like Ms Potts' chimney - were considered easy ways to gain entry to a house and so became popular hiding places for the footwear.

The shoe discovered at Alison Norman's house six years ago was also tucked away in a chimney.

A builder was restoring the late 17th Century fireplace when he found a package of thick, plain paper wrapped around a child's shoe on a brick ledge 30cm (11in) above the lintel.

Yet it was not contemporary with the age of the former farmhouse, explained Mrs Norman, who lives in Geldeston in Norfolk.

The shoe appears to have been hidden when the fireplace was covered up following a chimney blaze in the late 19th or early 20th Centuries.

Mrs Norman described it as a little, round-toed, right-foot shoe for a two or three-year-old, well made with a flat heel and very well worn.

She said: "A man in the village did tell me not to take it out of the house as it will bring back luck - but I have and nothing's happened."

This woman's shoe, which dates from 1675 to 1699, was found in a wall in Ely Cathedral

Reasons for concealment probably differed over time, according to historian Ceri Houlbrook from the University of Hertfordshire.

She said: "In earlier centuries, it might have been about protection from witches or the devil, one theory proposes that the shoes were intended to act as lures for witches, spirits, and other supernatural threats.

"The theory is that the evil force believes the shoe to be the person, attacks the shoe instead, and becomes trapped inside it. But more recently I think maybe they were intended to be time capsules.

"Or maybe the builders were doing it as a type of joke."

It might have been a workman who concealed a heavily-worn man's buckled shoe at St John's College, Cambridge, during an 18th Century redevelopment.

It was uncovered during renovations in 2016, concealed behind panelling between a fireplace and chimney in what had been the master's rooms.

Shoes have also been found secreted in manor houses, cathedrals, rural homes, townhouses and even Hampton Court Palace, according to Dr Houlbrook.

She said: "There are potentially thousands of pre-20th-century homes containing hidden shoes."

The shoe discovered at St John's College, Cambridge is a straight - designed to be worn on either foot. Left and right shoes were reintroduced from the 1790s onwards

The extent of the custom is recorded in the Hidden Shoe Index at Northampton Museum, set up in the 1950s by former curator June Swann, who realised the shoes were not just discarded or lost, but had actually been placed.

It lists just under 3,000 shoes found in properties from the Shetland Islands to the Isles of Scilly, with the greatest number being from the south-east of England.

The museum also holds 250 found shoes, the oldest dating to the 1540s and from St John's College, Oxford.

Current curator Rebecca Shawcross said the earliest hidden shoe discovered in the British Isles was found behind the Winchester Cathedral choir stalls, installed in 1308.

She said she receives two or three notifications a month from as far afield as the US, Canada and Australia.

The practice was taken to the New World by immigrants where it continued into the 1920s and 1930s, the curator explained.

However, in the UK the custom seems to have died out by about 1900, close to the time Mrs Norman's shoe was squirreled away.

The index lists any items found with the shoes. This mid-Victorian pair of boots was found in Brackley with items including a purse and teaspoons

The museum recently digitised the index, allowing academics like Dr Houlbrook to know for certain where shoes were placed, in what numbers, whether single - the majority - or in pairs.

The data confirms many of the reported shoes - nearly 900 of them - were children's, though it is unclear why.

Ms Shawcross said: "Was it that children were considered to have purer spirits, or, because so many children died, to ward off dangers?

"Or were there just more children's shoes around?"

Though so many questions surrounding the tradition remain unanswered, one thing is certain - the superstitious aspect lingers on.

Homeowners are increasingly unwilling to donate their finds to Northampton Museum "just in case", the curator said.

One finder from Kent told her removing a shoe from its hiding place brought "a whole catalogue of things that went wrong" - until it was returned.

The shoe discovered at St John's College, Cambridge, was returned to its hiding place after restoration work was completed

Ms Potts and Mrs Norman are also retaining their finds, though their reasoning is that the shoes are a part of the story of their homes.

The latter displays hers in a small glass box close to where it was found, while Ms Potts will be lending hers to an exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, external so it can "have its 15 minutes of fame".

As to why the custom began - and continued - it remains unsolved.

"Maybe it was so commonplace, there was no need to write it up, maybe it was only done illicitly - or kept secret because discussing it would cancel out its power," Dr Houlbrook suggests.

"We are taking educated guesses as to the reasons behind the practice, but they are still just guesses.

"That's the appeal - and the frustration."

- Published8 March 2014