World War Two pilot backs campaign to honour photographic unit

- Published

George Pritchard, second right, flew de Havilland Mosquitos on missions to capture vital images of enemy territory

During World War Two, the RAF's Photographic Reconnaissance Unit (PRU) produced more than 20 million images providing vital intelligence for the allied war effort. What were their missions like?

"When I look back I think 'why wasn't I scared out of my mind'?" says 97-year-old George Pritchard, a former PRU pilot. "But I wasn't scared at all."

By all accounts, he should have been scared.

Their planes were unarmed and stripped down which, while helping them outpace the enemy, left them more vulnerable to attack.

The survival rate in the unit was proportionally the second lowest of any Allied aerial unit during the entire war.

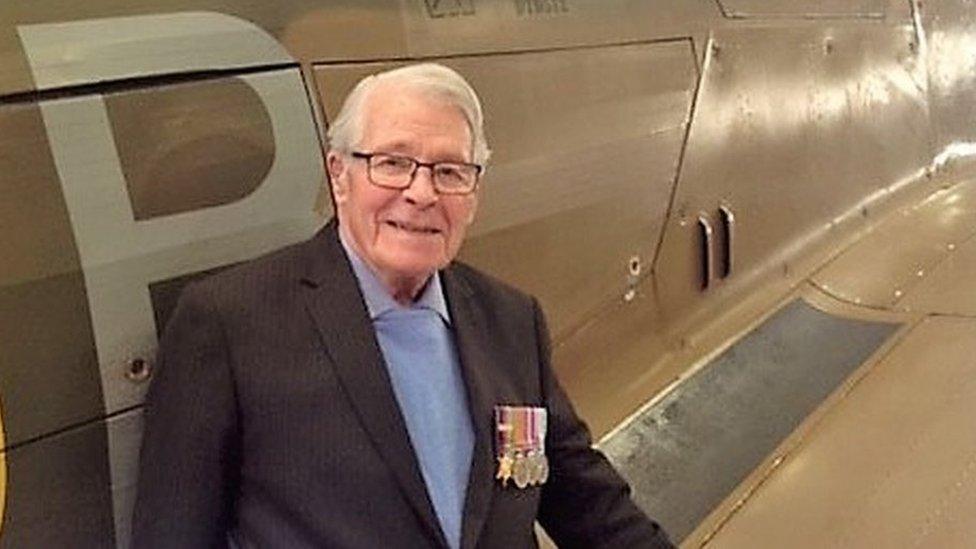

George Pritchard is one of a handful of Photographic Reconnaissance Unit pilots and crew still alive

In a recent House of Commons debate, external, MP Andrew Bowie said of the 1,287 men who flew in the PRU, 378 were killed.

Many were shot down over France, with 145 of those who died buried in unmarked graves.

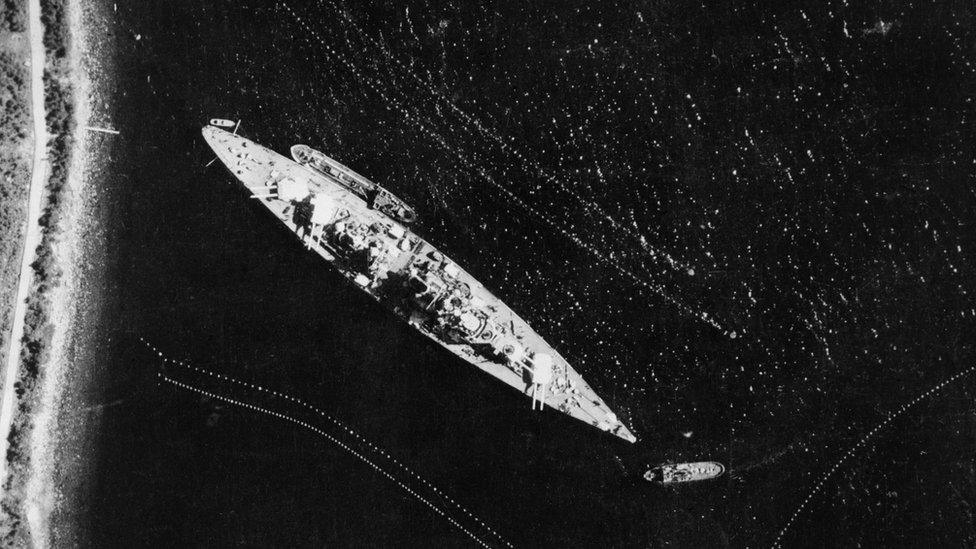

The images made by the unit flying in a variety of aircraft, including Mosquitos and Spitfires, helped in the planning of major milestones of the war, including the D-Day landings and the Dambusters raid.

The unit also first spotted the German V1 and V2 missiles.

Images taken by the PRU included this one taken in 1942 of the German battleship Tirpitz, moored in Narvik-Bogen Fjord, Norway

Mr Pritchard, believed to be one of just four PRU pilots still alive, has vivid memories of life in the unit.

"At three o'clock in the morning, we woke up with a cup of tea," he says.

"We would dive straight in to our flying suits. It would be a miserable morning with thick mists and rain, and dense cloud.

"We'd head down the runway, taxi round the perimeter and take off hell for leather completely blind.

"You could just about make out the runway between the lights."

Once the planes took off, Mr Pritchard says, they would reach 21,000ft (6,400m) before dropping to around 3,000ft (914m) to take pictures.

With one eye on fuel, the pilots would return to base after their mission was completed.

"When we landed, the cameras would be taken off and we'd have egg and bacon," Mr Pritchard says. "You'd get two hours sleep and report back for the next operation."

Mr Pritchard's desire to serve as a pilot was sparked one day in August 1940.

Then aged just 16, he had a job making ammunition boxes for the Acme Corrugated Cardboard Company, based on the edge of Croydon Airfield.

He remembers begging his then foreman for overtime, but was told he was too young and instead had to head home.

Once there he joined his mother and father in their garden, overlooking the airport.

Mr Pritchard remembers seeing planes overhead and what his father thought were parachutes coming out of them.

George Pritchard, far left, decided to join the RAF after his workmates were killed in a German bombing raid

"A matter of seconds" later, he says, explosions rang out. The parachutes had been bombs.

"Hurricanes came and chased them off or shot them down as I understand it," he says.

"I rode back to work and there was a policeman there. I said, 'I work at Acme', he said 'you used to, you don't any longer, it's no longer there'."

All of his friends and workmates had been killed in the bombing.

"I stood there as a 16-year-old and I cried," he says.

"I made my mind up, absolutely definitely, that I was going to join the RAF and get my own back."

Airmen studying reconnaissance photos during the Second World War

If his foreman had bent the rules and allowed him to continue working, he would have died along with everyone else.

By 17, Mr Pritchard had joined the RAF and eventually he became a pilot in the PRU.

Of his 22-strong joining cohort, only Mr Pritchard would survive the war. Those lost included his best friend.

The sacrifices of those who served in the PRU are now the subject of a campaign to build a monument in their memory.

It is spearheaded by the Spitfire AA810 Project, external, which is currently also rebuilding the Spitfire of PRU pilot Sandy Gunn, who was killed after being shot down over Norway.

The Spitfire of Photographic Reconnaissance Unit pilot Alastair "Sandy" Gunn, seen here in November 1941, is being rebuilt as part of a campaign to commemorate those who served in it

MP for Aberdeenshire Mr Bowie received cross-party support when he brought the idea to Parliament, including from Northampton South MP Andrew Lewer.

These days Mr Pritchard lives in Duston, Northampton, making Mr Lewer his constituency MP.

The Conservative politician said the "lively and active" Mr Pritchard is "living tribute to the outstanding work he and his fellow PRU personnel undertook in defence of our freedoms".

Mr Pritchard, however, says his proudest moments came after the war when making medical electronics.

His achievements in a life less ordinary include working on the first cardiac pacemaker and designing control panels for nuclear power stations.

In more recent years he has written children's books, illustrated by his daughter. The proceeds go to Great Ormond Street Hospital.

As for his wartime efforts, he says PRU pilots constantly lived in the shadow of death.

"You were young and you thought it would happen to everyone else but not you," he says.

"You have to have that, otherwise you would run away.

"I didn't think I was going to live. I thought I would catch it sooner or later. You would have guys there one morning and then you didn't.

"You got the feeling if your number's in the book, you will get it that day or time, so why worry in the meanwhile."

The war left harsh memories though.

Mr Pritchard remembers one occasion shortly when he was gripped with fear while walking through Notting Hill Gate underground station.

"I ran up 300 steps and collapsed on the pavement," he says. "I went to the doctor and he said it was a build up of stress over time.

"A vast number of pilots were murdered on the orders of Hitler. They were either hanged or shot.

"Nobody remembers them, how could they? With a monument with their names on, they'd always be remembered.

"It's a very good thing to do in remembrance of people who gave their lives up. I was just one of the lucky ones."

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external. If you have a story suggestion email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published17 October 2021

- Published13 May 2011