When the breakdancing craze swept Britain

- Published

For a few brief years in the 1980s, a phenomenon known as breakdancing swept across Britain in a flash of neon skiwear. Three decades on, a film has documented the experiences of teenagers in Nottingham, a city that fast became the unlikely epicentre of the craze.

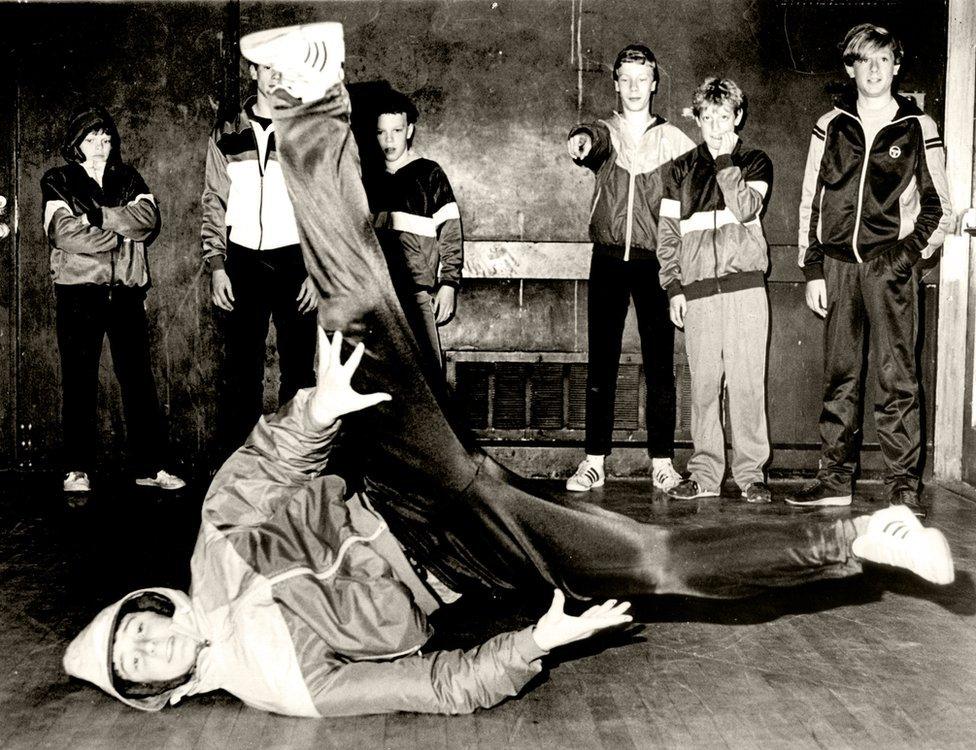

Across Britain in the early 1980s, tracksuit-clad youths began throwing down pieces of lino and pulling off robotic, seemingly gravity-defying moves.

It was called breakdancing and shopping centres across the land were witness to intense, gymnastic dance-offs, soundtracked by boomboxes blasting out the electronic sounds of early hip-hop.

Claude Knight, who has spent the past seven years making a film about the phenomenon that for a short time bonded often disaffected black teenagers in Britain, was 16 when he and his friends were swept up by the craze.

Their enthusiasm and can-do spirit was to lead to a city better known for the graceful moves of Torvill and Dean - and the sometimes disgraceful antics of Brian Clough - becoming the unofficial capital of British breakdancing.

Breakdancing in the streets of 1980s Nottingham

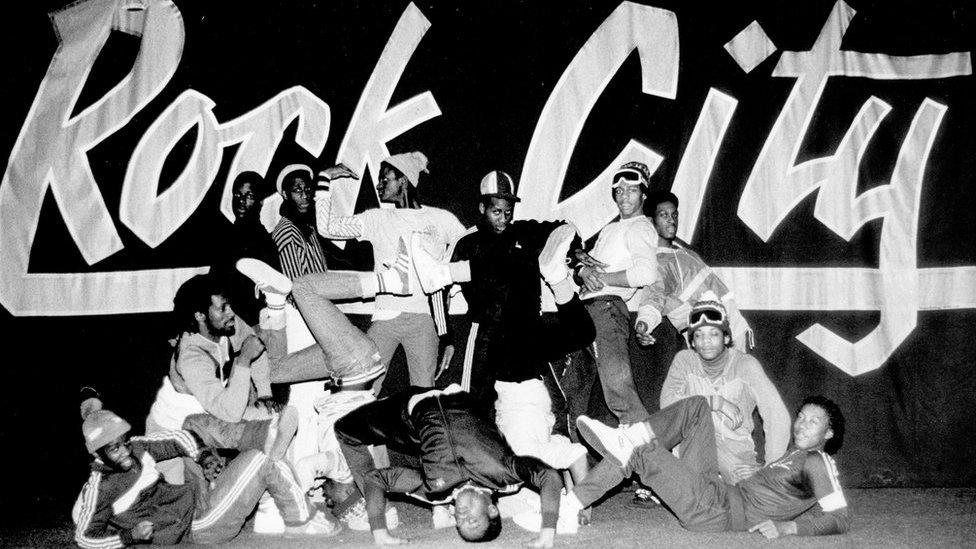

Each week, hundreds of "B-boys" attended Nottingham's biggest nightclub, Rock City, to show off their moves.

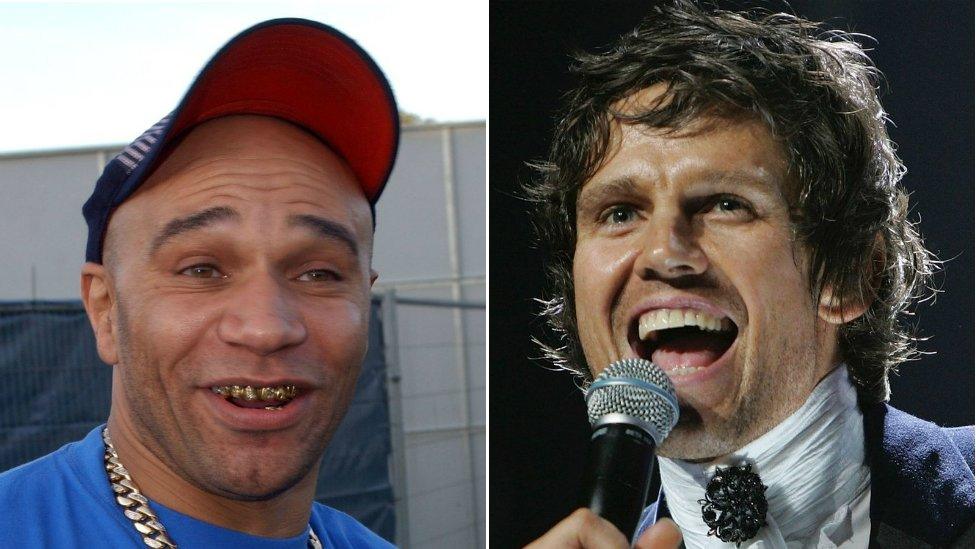

Drum 'n' bass DJ Goldie, who made the trip regularly from his hometown of Wolverhampton, described the club as his "second home" and Take That's Jason Orange was also a frequent visitor from his native Manchester.

Goldie said: "Nottingham Rock City - you heard about the infamy of it all before you actually went there.

"[Breakdancing] was everything, it was the music, catching the girl and looking great."

Knight, 48, describes his documentary film, NG83: When We Were B-Boys, which focuses on the phenomenon in Nottingham, as the "untold story" of the subculture.

Goldie and Jason Orange were regular visitors to Nottingham in the mid-80s

He said the city's period at the centre of the UK's breakdancing scene could be traced back to a performance by a US dance troupe, the WFLA crew, in Nottingham's Old Market Square in 1983.

The crew, who were dancing at locations across the UK to promote a milkshake, drew huge crowds in Nottingham.

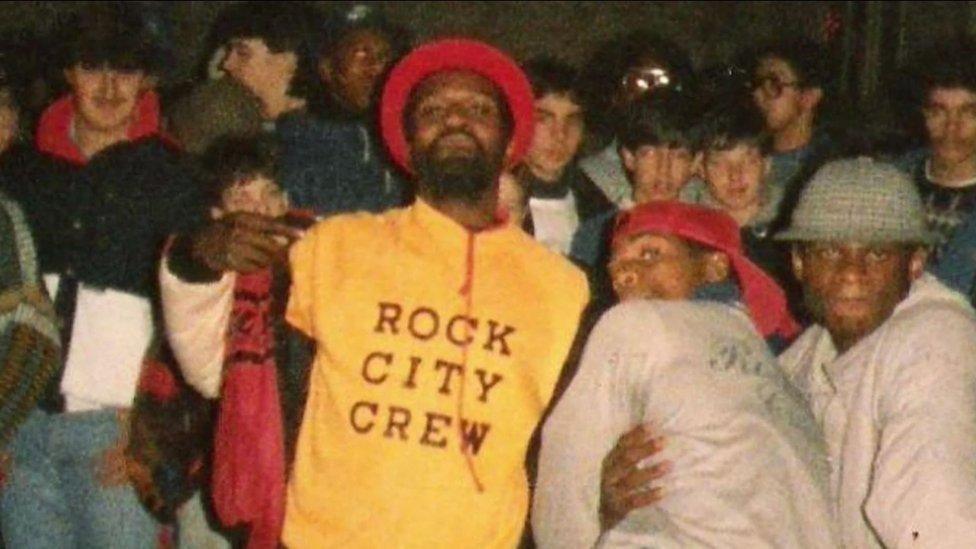

Knight, who was there, said the performance inspired dozens of young people, particularly black teenagers, to form crews across the city. One of these collectives, which Knight joined, was the Rock City Crew, which went on to become one of the most prestigious and successful in the UK.

People flocked from miles around to attend Rock City's weekly breakdancing nights

"I can remember being at school, sitting in geography or learning about French and German, thinking, I ain't gonna go to these places," said Knight.

"But through breakdancing, finding a crew, practising, saving money for tracksuits, going out, getting sponsorship, getting really good, you ended up going to places you never thought you'd go."

The Rock City Crew, managed by the club's DJ and manager, went on to perform around the world, supporting the likes of hip-hop legends, Afrika Bambaataa, Run DMC and Grandmaster Melle Mel and the Furious Five, as well as Rufus and Chaka Khan.

Knight joined the crew on tour as a rapper.

"After London, Nottingham was the next big thing, definitely. [Breakdancers] went to Wolverhampton, London, but it was Rock City that had the draw," he said.

"When we used to go out of town we used to have this 'we're better' attitude - Rock City Crew weren't the best breaking crew in the UK but were by far the most aggressive. Ask any B-boys, they were the ones you wanted to beat."

Breakdancing checklist

Like many breakdancers, a teenage Claude Knight would don skiwear before going out

Skiwear - All self-respecting B-boys would have to be seen in the latest Adidas tracksuit but skiwear was also a must. Knight said the lack of dedicated sportswear shops in Nottingham at the time made it difficult but you could pick up items from C&A

Lino - Pieces of lino, obtained from friends who might be getting a new kitchen or from house clearances, were ideal to breakdance on but a flattened cardboard box, held together with gaffer tape, would also do the trick

Boombox - "The big ones were very hard to come by," said Knight. "They were coin, so most people had small ones, tape recorders, but anything portable that you could hear music on would do."

Fat laces - Your shoes needed to look the part but only thin laces were available in early-1980s Nottingham. Knight said: "Some people used to get ice-skating boots and take the laces off because they were quite thick, or just stick bits of fabric over them to make them look thicker."

But why did Nottingham become such a centre for breakdancing?

Knight said the city's well-established black community in the 1980s was a big factor.

"We had the first race riots, external in the UK, so there was a tight-knit community," he said.

"Plus, music was a real escapism. [My parents' generation] didn't go to pubs, they had weekly parties at different houses and music was a big focus."

Rock City provided a battleground for crews across the country.

The breakdancing craze was short-lived but shaped the lives of many teenagers in the 1980s

But sadly for those whose horizons were expanded by the breakdancing movement, the craze proved to be short-lived and many were left with a hole in their lives by the mid-to-late 1980s as it fell out of fashion.

Knight said some turned to drink, drugs and crime.

"It fell off but you had a few who carried on," he said.

"It was a bit of a silly thing to people looking in but to some people it shaped who you were, me included."

Postman Karl Russell - AKA DJ D2 - was a breakdancing teenager

Karl Russell, now a 45-year-old postman in Nottingham, was a teenager when the craze came to town but his links with the scene are still strong - and like many B-boys he is still known by his breakdancing name: DJ D2.

"It just gave young kids a direction, it stopped negative things happening at the time," he said.

"When I look back, to put so much energy and effort into learning something, it was quite amazing how it focused people."

For Knight - also known as Scooby Doo - the film documents a 1980s subculture that gets little exposure in the media.

He said he was partly inspired by This is England, made by Nottingham filmmaker Shane Meadows and set around the same time period.

"I could relate it to it through the skinheads but it didn't represent my experience and the black experience," he said.

NG83: When We Were B-boys is being screened on 1 November at Broadway Cinema in Nottingham - the day after an over-40s breakdancing competition at Rock City.

It is due for release at selected independent cinemas in March next year.