They think they've got away: How to catch a historical sex offender

- Published

Actress Samantha Morton said when she first reported the abuse she suffered at the age of 13 "there was no support, no offer of counselling, no wanting to delve deeper"

Sex offenders think they'll get away with it. And often they do. Sometimes it can take years to bring them to justice, while others escape retribution altogether. So how do you go about making sure perpetrators of horrendous crimes committed in the distant past are caught and convicted?

As the years pass, abusers increasingly have the upper hand. Undetected, they can build up seemingly respectable lives. Even if convicted, elderly prisoners spend less time in jail simply because they don't have as long to live.

They also have the advantage of the vagaries of memory. Victims may have blocked out the abuse they suffered. Evidence - often one person's word against another's - can be hazy and conflicting, easy to cast doubt upon.

The people speaking out were in many cases children at the time of their suffering - and children can readily be portrayed by defence barristers as suggestible and easily confused.

The accused has no criminal record and appears to be a clean-living and valued member of society. Doubt sneaks in. And in a court of law, once doubt sneaks in, the prosecution's case can founder. The verdict? Not guilty.

So exactly what is the process of tackling these inbuilt disadvantages an accuser faces?

The abuse

One of the abusers at St Gilbert's, Brother Roderick (pictured centre) with the school at RAF camp in the early 60s. He died in 2012

Obviously, the first step of the process is the occurrence of abuse. Widespread at some care homes, schools, and youth detention centres, it often went unchecked until the victims could leave, the home was closed or the abuser moved on. In the past, vulnerable children were more likely to be seen as trouble-makers and less likely to be believed.

Even when concerns were raised, they were often dismissed. For example, at St Gilbert's - an approved boys' home for "young delinquents" in Worcestershire - pupils were beaten and raped by a religious order of Christian Brothers - despite the authorities knowing about one teacher having sex offence convictions, parents complaining and pupils telling the police.

An official investigation only opened in 2014. Most of the brothers are dead. They got away with it.

There are a number of ongoing investigations and inquiries - criminal and otherwise - into historical abuse allegations at institutions across the UK.

Coming forward

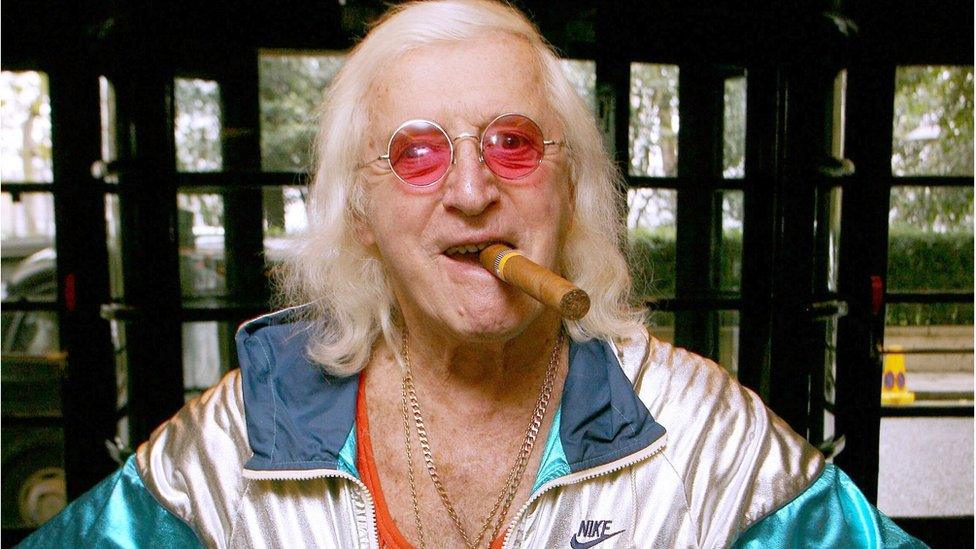

The number of historical sex offences recorded by police forces rose by 9% on the back of the Jimmy Savile scandal

If anything good could possibly come of Jimmy Savile's decades-long reign of abuse, it could be what has been dubbed "the Savile effect". In the wake of the scandal the number of historical sex offences recorded by police rose by 9%.

The National Association of People Abused in Childhood said victims now felt more confident about speaking out.

The actress Samantha Morton, who spent most of her childhood in foster homes or residential care in Nottingham, is one of many people who have come forward later in life with allegations of abuse during childhood.

"Nottingham in the 80s was rife with that [abuse from people in social services]," the Bafta and Golden Globe-winning actress said in 2014.

While the local force has said it has no record of the 39-year-old's complaint, two ongoing, separate operations by Nottinghamshire Police have provided an insight into the intricate nature of a historical sex abuse investigation.

Abuse at a number of former care homes, schools and a youth detention centre in Nottinghamshire between the 1940s and the 1990s is being investigated under Operations Daybreak and Xeres, external, which resulted in Andris Logins and Ivor Bethell being given significant jail terms.

To help explain how an investigation into men like Logins and Bethell reaches a conclusion, Nottinghamshire Police and the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) have guided the BBC through the process, from the moment an allegation of historical sexual abuse is made - to the emotional aftermath of a conviction.

The evidence

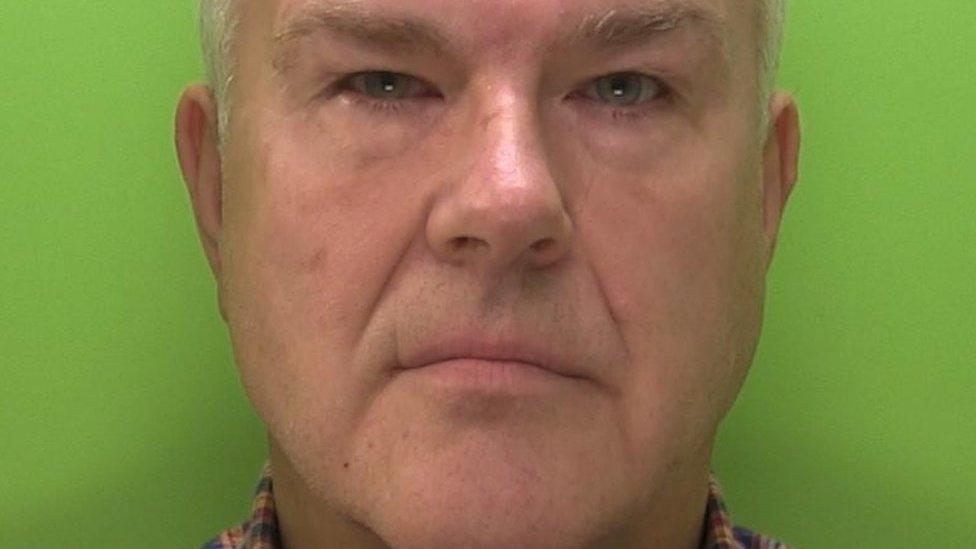

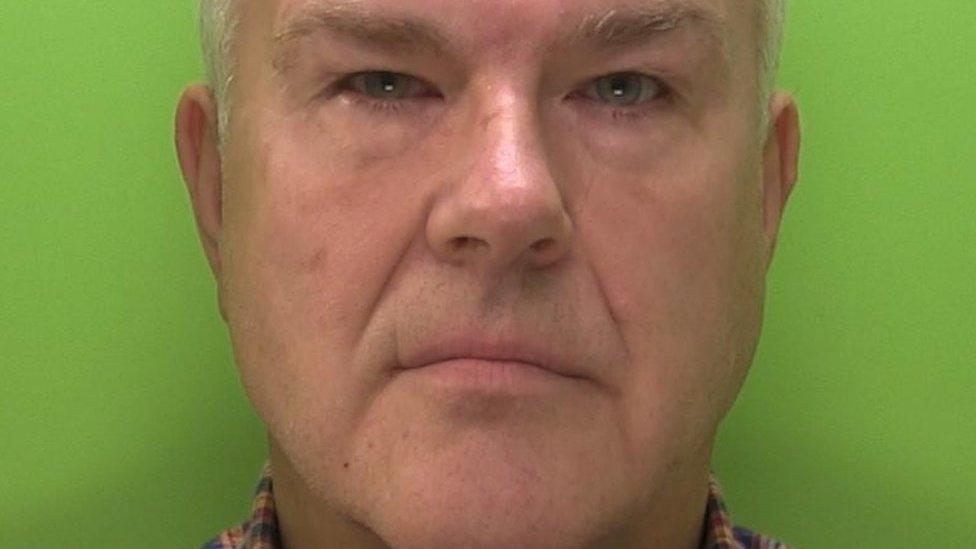

Ivor Bethell became the first person to be convicted under Operation Daybreak - although his offences were not related to abuse in children's homes

Supt Helen Chamberlain, from Nottinghamshire Police, says offences that happened a long time ago are especially difficult to deal with.

"If somebody were to complain they've been sexually assaulted in the street or abused in the home, what we have is very quick evidence from an alleged victim, forensic evidence which we can call on, and evidence from an offender if we catch them at the same time," she said.

"We've got scenes we can examine, CCTV, mobile phone and tablet data...but if somebody says they were sexually abused 40 years ago, you've got none of that available.

"You start going through files of schools, local authorities, some of which will have gone through the natural destruction process.

"It is not to say we don't believe the victims, but it is about trying to get sufficient evidence to corroborate their account."

The 'belief factor'

The judicial process is adversarial

According to one former Nottinghamshire Police officer, Jonathan Nicholas - who worked at the force for 30 years - belief was a "major factor" in alleged sex offences that previously attracted little or no formal action.

"There are several reasons: idle cops, untrained cops, the sheer cost and targets pressure. These are all in the mix at differing levels and in different cases," Mr Nicholas says.

"The cynical attitude of untrained and unsympathetic cops in the first instance which caused the victims not to be believed was a major factor."

While it is accepted societal attitudes have changed, giving more victims the confidence to come forward, there is a viewpoint that "the scales of justice" remain heavily balanced in favour of the perpetrator.

Jon Brown, head of development and impact at the NSPCC, said: "Cases like Savile have prompted victims to now come forward, but their recollections can be hazy, conflicting, sometimes sketchy, and combined with the lack of evidence, the perpetrator often will maintain their innocence on the basis of that.

"In criminal law, a case needs to be found beyond reasonable doubt. That makes it incredibly difficult to secure a conviction for historical sex abuse offences.

"It would be right to say the scales of justice are weighed pretty heavily in favour of the perpetrator - and the police and the perpetrators recognise that."

Building a case

Chief crown prosecutor Janine Smith said strength in the numbers of victims could contribute to the building of a case

So how do detectives and prosecutors build a case?

Janine Smith, chief crown prosecutor for the CPS in the East Midlands, said: "If you've got other victims, and if these victims are not necessarily known to each other or not had any sort of relationship with each other, that goes to show the credibility.

"Are all these people making up the same thing that happened to them by the same individual in similar circumstances?"

CPS East Midlands is part of a national pilot that sees a CPS lawyer based in a local police station to offer advice and guidance in the early, pre-charge stages of an investigation.

That means, according to Supt Chamberlain, it is now "rare" that officers spend time building a case against a historical sex offender, only for it to be dropped by the CPS.

Strength in numbers, in terms of victims, can also be achieved through media communications made by the police, the NSPCC's Mr Brown said.

"Lawyers will object to it, saying it's a fishing expedition, but if it recognises abuse is rarely perpetrated against one victim, how difficult it can be for victims to come forward and the like, then sometimes it can be very important for these communications to be made by the police," he said.

In court

Teacher Roger Caffrey touched young girls during lessons

The judicial process in the UK is adversarial. Lawyers for each party argue it out, each trying to convince the jury. Aspersions are cast, doubts sown, characters ripped to pieces.

Mrs Smith said that while lawyers tend not to use the courtroom as a stage, there can be an element of bravado as both the prosecution and defence counsel strive to present a clear, engaging case to the jury.

"It's something that can be used to great effect, once you're satisfied that the case passes the code test, external," she said. "There's a lot of thought that can go into cases about presentational issues.

"We have to present it in a way that the jury understand and their attention is captured, and the defence will do exactly the same.

"It's not doing anything underhand and it's what we would expect from prosecuting counsel."

Behind the pomp and ceremony, there are witnesses and victims, many of whom may be strangers to a courtroom and terrified of giving evidence, in part due to the prospect of being grilled by a seasoned advocate.

One victim went to the police more than two decades ago, but no charges were brought due to a lack of evidence.

Before her abuser Roger Caffrey was eventually jailed for 17 years for her rape, among other offences against other victims, she told Nottingham Crown Court: "I took this to the police 22 years ago and I thought justice would be done. It was one word against another."

Caffrey, a teacher, began touching another victim over and under her clothing in his classroom store cupboard or while she read aloud in class.

She later told the BBC: "He was a teacher, he was in a position of authority," the victim said. "Physically, he was a big, imposing character. He had big hands, I was just a little child. The police came to me. My name had been given as a possible victim or witness.

"I was relieved more than anything. I thought it was about time the truth came out - he'd got away with it for too long."

The improvements

Andris Logins was in his 20s when he abused children at Beechwood Community Home

Supt Chamberlain said Nottinghamshire Police has just finished some training with the CPS around credibility, meaning the credibility of events - rather than the credibility of the alleged victim - is questioned in court.

"What you don't see in court are rape victims, for example, being asked what they were wearing or what they were doing on their own," she said. "What we're trying to do is make the evidence more 'victim-centric' and give more focus to the victim.

"For example, the defence, prosecution and the CPS will sit down and decide what questions will be asked during cross-examination."

The aftermath

A BBC documentary featuring the Beechwood Community Home facility was broadcast in 1981

Figures obtained by the BBC revealed Operation Daybreak has now received 391 separate allegations, while another 223 complaints have been made to Operation Xeres.

Nottinghamshire Police said 236 people have been named as perpetrators across the two inquiries - although 24 of those alleged abusers died before they could be investigated.

Despite reports of sex offences continuing to rise, Supt Chamberlain said some victims may never feel confident enough to come forward.

"It's not stopped increasing so it's hard to say when the tap's going to turn off because I don't think it will," she said.

"It's very sad to know there are people out there who have suffered abuse in the past and haven't come forward.

"It's unfortunate, but the criminal justice process has improved tremendously to give people the chance to tell their account, be supported and get the case to court."

In the words of one of Caffrey's victims: "I wasn't even particularly bothered that he would get a huge, long sentence. I just wanted somebody to say, 'you're guilty, you did this' and that we were believed.

"I didn't feel sorry for him at all but a bit sad. That's his life and that's the sort of person he chose to be. A good teacher is someone you remember for the rest of your life and he could have been that teacher, but he wasn't, he was the worst kind of teacher.

"That's his legacy now… and now he's going to end his days in shame."

- Published21 April 2016

- Published23 March 2016

- Published4 February 2016

- Published20 January 2016