Flying a drone: How easy is it to fly one safely?

- Published

Lots of people will have unwrapped drones for Christmas, and a fair few will probably end up crashing them. So how can drones be flown safely? BBC reporter and nervous technophobe Caroline Lowbridge explains how she reluctantly learned to fly one.

When my manager first told me he thought it would be a good idea for me to learn to fly a drone, I was perturbed.

"Let's get a drone!"

"I, er... what?"

"A drone! Let's get one. We can send it up to… I don't know. Loads of stories!"

"You want ME to fly it?"

"Yeah! Imagine the possibilities."

"You know I failed my driving test nine times?"

"Oh."

If I seemed reluctant, I was. I'd never "remote controlled" anything in my life. Even my limbs - which I directly control - have a tendency to bump into things.

My manager told me to film a Rocky-style training montage

What's more, I struggle with relatively simple gadgets. I've still got a CD Walkman because I can't face putting music on to an iPod. Surely it would be irresponsible to give me something as complex, and potentially dangerous, as a drone?

I started looking into the rules. The government recently proposed forcing drone users to take a safety test, but at the moment, any consumer in the UK can buy a drone, get it out of the box and fly it around without any kind of permission.

However, I quickly discovered that anyone using a drone for work needs to do a tough course about aviation law and safety, pass the drone equivalent of a driving test, then get permission from the CAA.

Phew, I thought. It looks like I've escaped this whole drone thing. Surely my manager wouldn't put me through several months of mental torture?

Unfortunately, he was not deterred.

Consumers should not fly over or within 150 metres of any congested area or large gathering of people

I started calling approved "drone schools" from a list on the CAA website, external, but the first one I tried was a bit sniffy.

"Do you have any practical flying background?"

"Er… no."

"Do you have any background in photography or filming?"

"Not really."

"Did they just pull your name out of a hat?"

Beware of unexpected dog walkers when flying a drone

I became increasingly apprehensive but eventually, one organisation - Rusta - reassured me a bit. They didn't seem too worried about my lack of experience. The trainer even told me his eight-year-old daughter flies a drone around.

"A lot of these systems are so easy to fly it's unbelievable," he said.

Maybe for your average person, I thought. What about a clumsy, anxious Luddite who's paranoid about slicing someone's ear off?

Ground school

I looked on in confusion as Sion Roberts - holding a huge propeller - talked about something called "props"

Sion Roberts, our trainer and a former RAF pilot, kept talking about "props".

"The pitch of the props affects how much lift they generate," he told us.

"It's vital that you check your props both pre-flight and post-flight."

I looked around nervously. I thought I'd been keeping up, but I'd obviously missed something.

About two-and-a-half hours later I finally realised that "props" was short for "propellers".

The huge propeller he was using to point at the projector screen should have been a clue.

As you can probably tell, I was a little bit out of my depth.

Drone training - or more accurately, Unmanned Aerial Vehicle training - is largely aimed at commercial photographers and film makers. You spend two days studying theory in a classroom before sitting an exam. Later, you return to complete the practical flying test.

I did a course run by Rusta, one of several training providers approved by the Civil Aviation Authority

I felt a bit out of place because I was the only woman on the course - apparently 98% of people who do this course are men.

Also, my classmates each had some kind of enormously impressive technical background. One was a serving military pilot. Another had actually built a drone himself.

By comparison, my proudest such achievement was partly assembling an Ikea wardrobe (I still haven't put the doors on).

It wasn't long before things got even more intense. Within just a few hours, we were tackling subjects such as meteorology, cloud classifications and "vortex ring state" (don't ask). I felt like a Nasa cadet.

So, why is it so demanding? You can buy a half-decent drone for £80 in Argos, and presumably a lot of people have. Does it need to be so gruelling and expensive (this course would normally set you back £1,000) to learn how to fly one safely?

Well, a drone has the potential to cause injury and endanger other aircraft.

What could go wrong?

Pilots and others in the aviation industry are concerned about drones colliding with aircraft. In the UK alone, 64 near misses were reported from January to November 2016, external.

Drone propellers can cut and injure people. Pop star Enrique Iglesias, external was injured when he grabbed a drone during a concert while a toddler in Worcestershire lost an eye after a drone propeller sliced it in half.

Of course, a drone can also fall out of the sky, like the one that smashed into the ground next to skier Marcel Hirscher, external in 2015.

Therefore, if you're going to be using a drone regularly for work you have to go through this robust training.

Unfortunately it involves learning how to decode 59-digit aviation weather forecasts such as this:

EGNX 140504Z 1406/1506 30009KT 9999 FEW040 PROB30 TEMPO 1500/1506 8000

I had a lot of studying to do.

Maiden flight

I was given a drone flying lesson by Sion Roberts, head of academy for Rusta

"Uh-oh," I said as the drone drifted off in the direction of a dual-carriageway.

I'd turned the GPS off. I'd been told to do it, and I knew what was going to happen. But it was still a bit of a shock - much like riding a bike without stabilisers for the first time.

This was my first attempt at drone flight. Sion, who was watching a few metres away, had taken pity on me and agreed to give me some pointers. He was wearing aviator sunglasses, like a proper pilot should, while I squinted at the bright morning sky.

Drone batteries can be explosive and need to be stored safely, but we might have been a bit overcautious

Against all odds, I'd actually passed the theory test - but I can't stress enough how difficult it had been. I spent two days studying in the classroom and two entire evenings revising, and by the morning of the exam I felt so worried my eye started twitching.

That was a couple of months ago. In the meantime, I'd spent hours and hours filling in seemingly endless BBC paperwork. Every possible risk had to be assessed and minimised.

My boss even bought a surplus ammunition tin for storing the drone batteries, just in case they exploded. In hindsight, that was probably overkill.

Drone basics

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), commonly known as drones, are aircraft operated remotely without the pilot being aboard

Small drones fitted with cameras, including those sold commercially to hobbyists, are increasingly being used by broadcasters, filmmakers and photographers

Some drones have fixed wings, like an aeroplane, but the most popular types have multiple rotors

Most small drones are powered by batteries and operated using gamepad-style remote controllers

Consumer drones range in price hugely, starting at about £40 for one with a camera, with more advanced models costing more than £1,000

So when it was finally time for my first flight, I'd forgotten a lot of what I'd learned on the course.

But with Sion's guidance I went through the 20-point checklist, which included testing the gyroscope, accelerometer and compass. I also made sure the aircraft was connected to at least six GPS satellites and fixed my maximum altitude at 400ft - the limit set by the CAA.

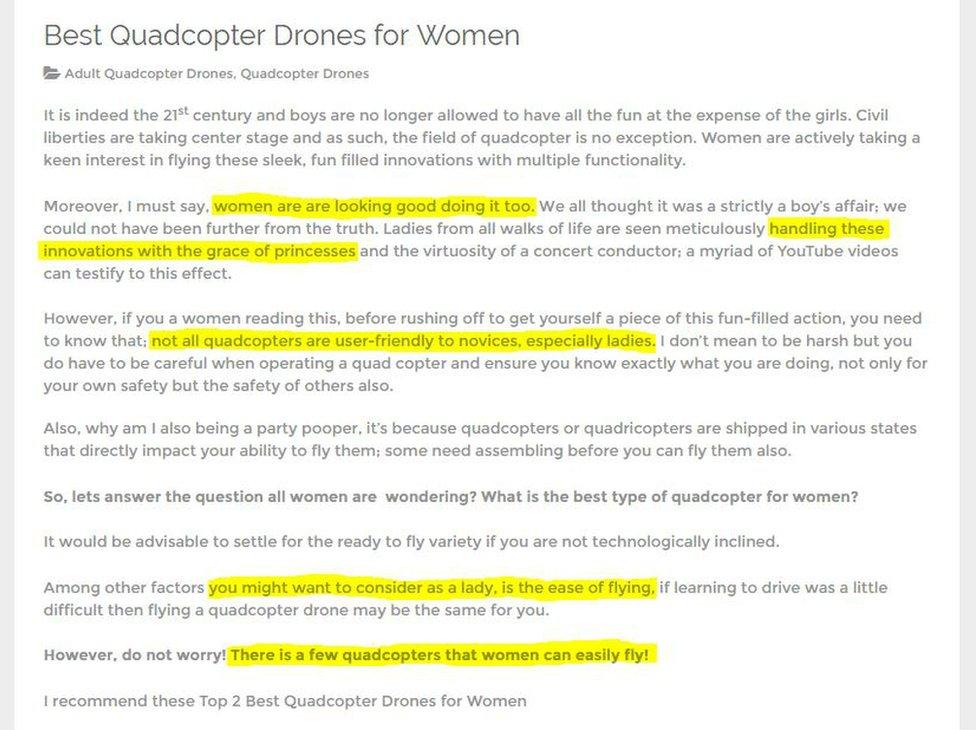

I'd previously come across some "drones for women" advice, external that was so sexist and patronising it was funny. Along with a photo of women in skimpy vest tops it warned that "not all quadcopters are user-friendly to novices, especially ladies".

However, controlling the drone was a lot easier than I expected. I pushed up on the stick and it rose smoothly into the air. I released the stick and it hovered in place. I tried flying it left and right and the aircraft followed. It was very responsive and steady - almost like a computer game.

I discovered some patronising advice aimed at female would-be drone pilots

Then Sion asked me to turn the GPS off. This is something that crops up on your final test, and he wanted me to experience it. That's when it got tricky.

Even though there wasn't much wind, the drone was immediately pushed towards the busy road. Admittedly, the road in question was quite a long way away - well within safe limits - and the drone only drifted about 10 metres, but it was enough for me to imagine causing a massive, catastrophic pile-up.

I didn't have the courage to fly without GPS for long. After no more than a few seconds I switched it back on and the drone quickly stabilised.

That's the dilemma with drones. Features such as GPS mean a relatively inexperienced person can fly them much more easily than, say, a radio-controlled helicopter. But the GPS signal can fail, or there could be some other kind of malfunction, causing an inexperienced pilot to lose control.

If you want to see what can happen, type "drone fly away" into YouTube, external and you'll find countless videos of them flying off and crashing for no apparent reason.

My drone was filmed in the air by another drone, flown by a colleague of Sion Roberts

Flight practice and test

I almost crashed the drone into my colleague Chris

Before taking the test I needed to record at least two hours of practice in my flight log, so my boss set me the task of filming a Rocky-style training montage.

Despite my apprehension my confidence quickly grew, and I actually started to enjoy whizzing the drone around my local park.

Within a few weeks I even felt brave enough to fly around a dog assault course I spotted in the park, weaving the drone in between trees and up and down a ramp.

On one visit my cameraman, Chris, and I took along a paper target which we thought would be cool to land the drone on.

Very quickly, it started going wrong.

I tried - and failed - to land on a paper target which kept blowing away

Each time I tried to set down on the paper target, the downwash from the drone blew it away, even when we tried weighing the target down with stones.

Before long, the drone's batteries started running out.

With the drone just above our heads, I once again tried to manoeuvre it over the target. It responded strangely, pulling in the wrong direction. Then suddenly, it shot off towards Chris.

Fortunately it headed for his legs, rather than his face, giving him time to follow our emergency procedure of "run in the opposite direction".

Needless to say, I felt very guilty about almost injuring my colleague.

So, what happened? Well, I'm not certain, but my best guess is that because the drone's battery was low, it had been trying to land itself.

I went back to Sion for advice, and he thought this could have caused the mishap.

"Your battery hit its critical level so the flight control computer sent it on its 'failsafe' or 'get you home' route. It may have tried to climb to its safety altitude hence why it seemed a bit out of control," he said.

It was the closest I'd come to disaster and, if anyone from the CAA is reading this, I'd like to point out that I've learned my lesson and will never do anything reckless again.

I made sure these railway lines were not in use before flying the drone over them

Soon afterwards, I took the flying test and - although I was extremely nervous - I passed with no major problems. I even got two commendations for my risk assessment and emergency procedures.

Then there was even more paperwork - this time my application to the CAA, which included writing a 45-page Operations Manuals setting out how I intend to operate my drone safely.

My "drone licence" - technically called a Permission - arrived back about a month later. It means I can now use a drone for work, and unlike hobbyists, I can fly in congested areas - although I still need to make sure I don't fly near buildings or random members of the public who aren't "under my control".

So, how easy is it to fly a drone?

I learned to go through a safety checklist before each flight, which includes making sure the propellers are fitted properly

I discovered that consumer drones are designed to be user friendly so that anyone can control them, even me.

I could probably have followed the instructions out of the box and worked it out for myself. However, the risk of something going seriously wrong would have been a lot higher because I wouldn't have gone through all the safety checks.

I feel extremely fortunate to have had an expert like Sion helping me, but realistically, most consumers are unlikely to take an in-depth course like the one I did.

So, what can the average person do to fly more safely?

Following the CAA's Drone Code, external - which sets out the basic safety rules - would be a start, and hopefully awareness of this will spread as drones grow in popularity.

Some retailers have started offering free flight lessons when people buy drones, which can only be a good thing.

If people can't get a free lesson - and don't want to pay about £100 for one - perhaps they could find a more experienced friend to help them.

And this might sound obvious, but don't do anything blatantly reckless like flying near an airport, or, erm, flying with a low battery.

Basic drone rules

Drones should be flown no higher than 400ft

Always keep your drone in sight

Fly no higher than 400ft

Fly no further than 500 metres away

Don't fly near airports or other aircraft

Keep at least 50 metres away from people, unless they are under your control

Keep at least 50 metres away from vehicles, vessels, buildings or structures that are not under your control

Don't fly over or within 150m of a congested area or large gathering of people

Get permission from the landowner of wherever you take off and land

- Published25 December 2016

- Published25 December 2016

- Published25 December 2016

- Published25 December 2016

- Published21 December 2016

- Published6 September 2016

- Published7 July 2016

- Published26 November 2015

- Published5 March 2015

- Published7 April 2014