Miners' strike: The decades-old feud that still divides communities

- Published

In Nottinghamshire, the majority of miners carried on working

"Even now people ignore me if I say hello," says Yvonne Woodhead, 35 years since her husband decided to join miners across the UK in going on strike.

Between March 1984 and March 1985, more than half the country's 187,000 miners left work in what was the biggest industrial dispute in post-war Britain.

But in Nottinghamshire, the majority of miners chose to carry on working, leaving whole towns and villages divided between strikers and "scabs" - those who crossed the picket line.

Today fewer and fewer remember March 1984 - and many that do might wish to forget it - but the tensions the strike created are often only just below the surface.

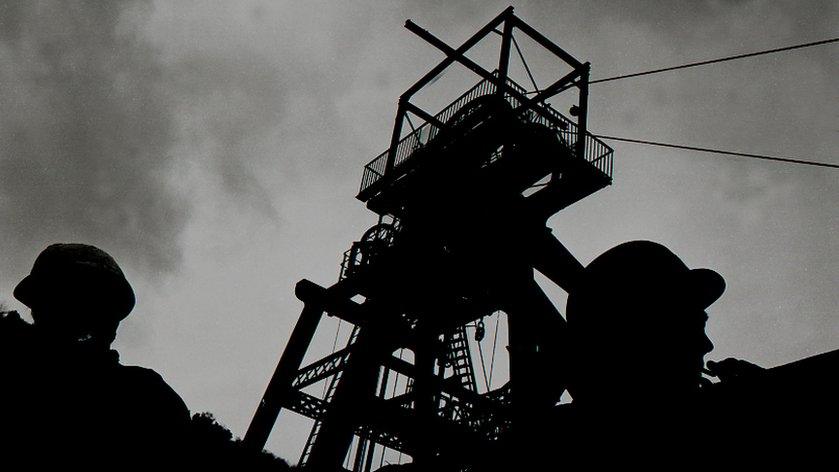

Nottinghamshire pits remained open, helping the government keep the power stations running

Mrs Woodhead, who lives in the village of Blidworth, says some people still cross the road when they see her coming.

"Some people haven't spoken to each other since it started," she says. "It goes deeper than deep.

"There are people here that will not go into a certain pub or a certain shop because 'that's where the scabs went'. People made up their minds in the first month of the strike and stuck to it."

Mrs Woodhead, now 68, remembers how during the strike, she borrowed plastic cups from a local school for the strikers' children to use.

When she handed them back washed and cleaned, she says some of the wives of those who were still working threw them in the bin.

In some areas almost all the miners went on strike

The nationwide strike was a last attempt by the mining unions to save the industry after the National Coal Board announced 20 pits in England would have to close with the loss of 20,000 jobs.

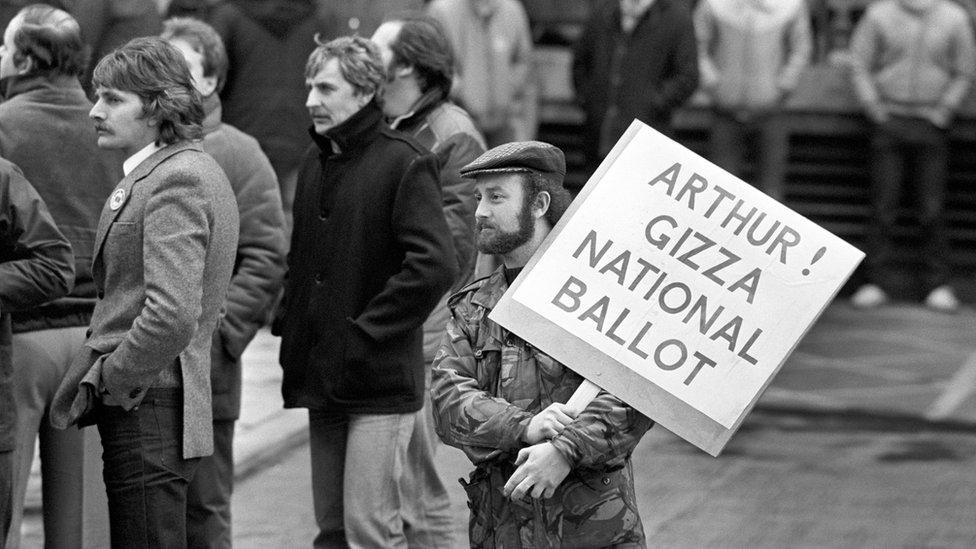

In Nottinghamshire, a ballot was held and miners voted to carry on working. Only a quarter of the county's miners joined the national strike, according to the National Coal Mining Museum.

In other areas it was much better supported - for example in south Wales, 99.6% of the 21,500 workers joined the action and, a year on, 93% were still not working.

Nottinghamshire was the home of the Union of Democratic Mineworkers (UDM), whose members continued to work after splitting from the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), arguing the strike had not been approved in a vote.

The head of the NUM would not hold a national vote on the strike

Those who went on strike earned no money and were ineligible for benefits as their industrial action was deemed illegal; they had to rely on scrimping, savings and handouts.

Mrs Woodhead and her family gave up "luxuries" like television and heating because they couldn't afford them, and relied on donations from solidarity movements in the USSR and Poland for Christmas presents for their children that year.

Mrs Woodhead, who is now a councillor, still has mugs, plates and badges from the strike but keeps them boxed up nowadays

"We were used to having food on the table, clean and tidy houses and the kids well-clothed, but we hit rock bottom," she says.

"We had nothing, absolutely nothing."

Women supported the miners in soup kitchens and on the picket line

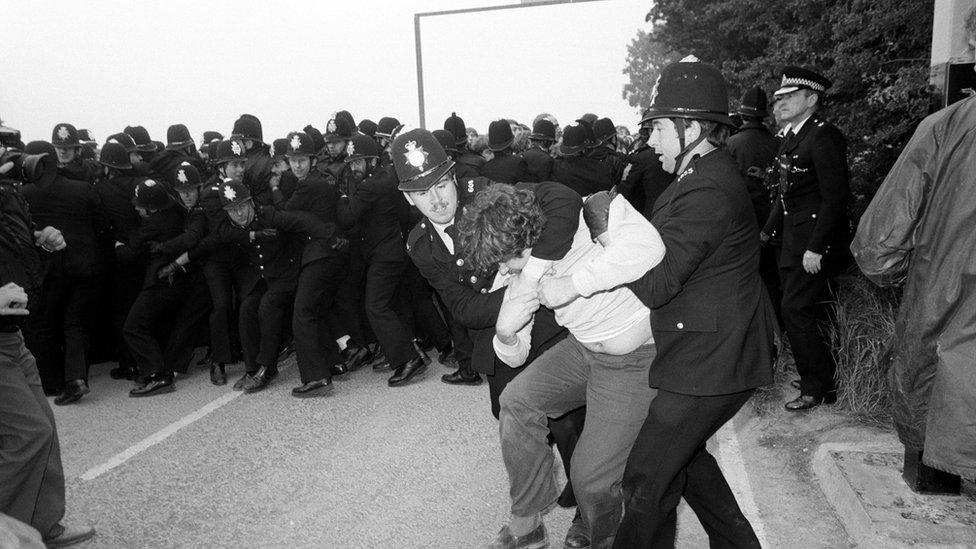

Striking miners lined the streets leading to pits in an attempt to stop their colleagues from going to work and, as tensions rose, a 24-year-old picket from Wakefield, David Jones, died hours after being hit by a brick in the Nottinghamshire town of Ollerton.

Local resident Sue Howells, 64, found out about the death on the television news. She immediately jumped in the car to stop her husband David crossing the picket line, fearing for his life.

"I found him and said: 'You're coming with me, or you can go up that lane and get yourself killed.'

"The people in the crowd were throwing bricks, they were carrying all sorts of things - they came for business," she says.

"I didn't know them from Adam; it was frightening.

"We sat for hours talking about it when we got home, but I'd rather have him at home with me than six feet under, so we had to do what we had to do."

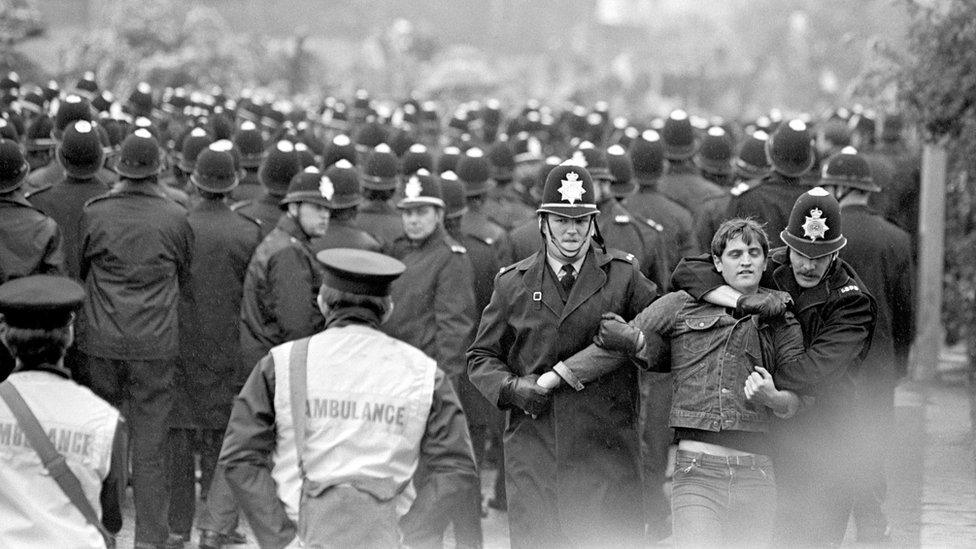

Thousands of pickets and police officers clashed at Orgreave in some of the most violent confrontations witnessed during the year-long miners' strike

Mrs Howells says people who she had known for years then started ignoring her in the street, while some were shopping 12 miles from home to avoid meeting someone from the "wrong side" in the supermarket aisles.

Although she says she never resented anyone for not striking, when people treated her differently she thought: "You can get stuffed - you know something ducky, my husband is fighting for such as you."

Two miners from opposite sides meet for the first time since the strike

During the strike coal production dropped by more than half but the government had stockpiled in preparation and, with supplies coming from the still-working pits in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, power stations were able to stay open.

On 3 March 1985, the NUM executive, running low on funds and with striking families struggling to feed, heat and clothe themselves, narrowly voted to end the industrial action, without concessions from the government. Almost a year after it had started, the strike was over.

Flying pickets came to Nottinghamshire to bolster the numbers of demonstrators, and the government brought in extra police officers to deal with them

The defeated miners returned to work and the pit closures would go ahead. The country's last deep coal mine, Kellingley Colliery in North Yorkshire, shut in 2015.

By 2017, only about 1,000 people were working in an industry which, at its height, employed more than a million people, according to government statistics.

After the strike ended, Mrs Woodhead joined the Women Against Pit Closures campaign and got involved with politics.

She now represents Rainworth South and Blidworth as a Labour councillor and believes the pit closures show they were right to strike.

The miners ultimately went back to work with no concessions from the government

Mrs Howells went to work in a factory and now spends much of her time organising community events for the elderly women of Ollerton after the closure of the village's miners' welfare club left them with nowhere to meet and socialise.

She gets help from the wives of men who went on strike from the beginning of the dispute and says that although she does not hold it against them, they do not talk about it.

"In Ollerton, there's them that talk to each other and them that don't," she says.

And will that ever change?

"No, not now."

- Published3 September 2018

- Published12 March 2014

- Published13 January 2014

- Published2 January 2014