Memories of a novice journalist from the miners' strike

- Published

- comments

Striking miners watch coal leaving their pit under police guard

It's hard for the twenty-somethings of today to understand just what living in Britain felt like back in the 1980s.

Industrial relations then and now bear no relation to each other.

A picket today is supposed to have no more than six people on it, external. When I went out to report on my first miners' strike picket in the heart of the South Wales coalfield it was a rather different story.

Crowds of miners would form a throng at the colliery gates before dawn to blockade it. The simple aim was to stop anyone going in to work and prevent coal lorries from being driven out.

It was a powerful force.

To a novice hack it could seem as rowdy, deafening and as scary as a baying 1980s football crowd, unrestrained by today's all-seater stadiums.

However in this fixture everyone was playing for much higher stakes.

Tough times ahead - miners' leader Arthur Scargill with the Coal Board's newly appointed chairman Ian MacGregor in September 1983

Whole communities depended on the local pit. Emotions were running high and it felt, in a real sense, that a revolutionary battle was being fought; 'the people' versus 'the state'.

Neither side could afford to lose.

Two sides of one story

The miners' wives came into their own with their effective campaign to back their men's cause. South Wales was one of the most solid areas to hold the strike.

Nevertheless, a small number wanted to go to work and were prepared to run the gauntlet of their colleagues.

Friendships would be broken and remain so for decades.

As a journalist trying to report both sides fairly was a difficult task as the truth wasn't easy to define.

Each morning the NUM and the NCB would both release figures for the number of miners who'd crossed the picket lines.

The union and management figures never tallied and often were so far apart as to render both useless.

When I was reading the breakfast news on Swansea Sound we always gave out both sets of figures.

Quite literally there were two sides of the same story, but no-one really knew how it would end this time.

Power cuts and a 3-day week for industry were the norm in 1972

I had childhood memories of the 1970s miner's strike that made power cuts a regular frustration and ultimately brought down a government.

As a child, eating meals cooked on a camping gas stove in our Northumberland home seemed rather fun.

It was only witnessing a miners' strike as an adult that I understood that whichever way it went, the outcome would be historic.

It wasn't all black and white, them and us.

Local managers and union officials weren't necessarily as entrenched as their leaders.

Philip Weekes was the area's coal board chief whose 2003 obituary speaks volumes about what went on behind the scenes, external.

Scargill and the media

There were even moments of unexpected humour.

Arthur Scargill, external was due to visit and so we sent out a reporter whose accent happened to be as "valleys" as you could get.

The NUM president was no fan of the media but we hoped David might at least get a few words with him on tape.

As he stepped off the train our intrepid colleague introduced himself as a reporter with Swansea Sound.

"Oh I'm so sorry for you," Mr Scargill replied and marched into the distance.

The 30 year rule means I can probably divulge now that David was gutted. Away from the news desk and in a personal capacity he had helped to raise money for the strikers' families.

It was difficult to be a "local" journalist and maintain impartiality when you saw first hand the impact the strike was having on the communities you broadcast to.

I knew that what I was watching in South Wales was being replicated in my native North East.

Turning point

As the dispute dragged on, more miners felt they had to return to work to make ends meet.

In South Wales the dispute would also cross a line.

The death of taxi driver David Wilkie, external shocked the country.

As he took a rebel miner to work a concrete post was dropped onto the vehicle from a bridge by two striking miners.

Instead of denouncing the guilty men, a local union rep said the strike-breaking miner would have the taxi driver's death on his conscience.

It shows just how high feelings were running back then.

That dreadful episode aside one might have thought 30 years would have let bygones be bygones.

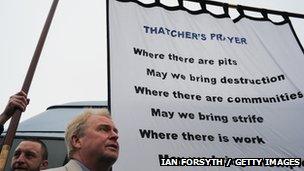

Margaret Thatcher's death put paid to that notion.

The former Prime Minster's funeral coincided with an event at Easington Colliery in County Durham to mark the anniversary of the pit's closure. Not many tears were shed there that day.

Memories run deep in Easington Colliery where Margaret Thatcher's funeral coincided with a rally to mark the pit's closure

A lot has changed since then.

Union laws have since stopped mass gatherings like those that dominated our TV news screens in the 80s.

The police have worked hard to regain the public's trust after being seen by some as an arm of the state.

Yet, for those who lived through the strike the dispute will still divide opinion.

With the pitheads nearly all gone and some children never having seen a lump of coal, it seems younger generations will only have scenes from Billy Elliot, external to get a sense of what mass industrial unrest is like.

The reality is it was much tougher than that - on everyone.

Inside Out can be seen on Monday, 13 January 2013 at 19:30 GMT on BBC One in the North East & Cumbria and nationwide for seven days on the BBC iPlayer.

- Published13 January 2014