'I never knew my mother escaped the Holocaust'

- Published

Michael standing at the cemetery where his family are buried

Michael Goodwin was brought up by adoptive parents in Australia believing he was of Irish Catholic descent. He grew up wanting to find out something about his mother. Now at the age of 80 he knows, at last, the truth about his real family.

It was only in later life that Michael Goodwin discovered he was Jewish.

Having been adopted at the age of seven and raised by a middle-aged Australian couple, he had married, settled in Perth and started a family of his own.

He was raised as a Catholic by his adoptive parents, who had been told he was of Irish descent.

Michael's great aunt - whom he never met - standing next to the same memorial

And yet, within him, he had a niggling sense there were crucial parts of his story that were missing.

"I always wondered who I was," said Michael.

He had tried to call on the authorities at the children's home where he had lived prior to his adoption to release paperwork about his birth family.

"There was a shut door," he said. "I couldn't find anything out whatsoever."

A film was made about the work of the Child's Migrant Trust, starring Emily Watson

Michael knew he had been brought to Australia from Britain, where he had lived prior to his adoption.

It was only when, in 2009 and 2010, the British and Australian governments apologised, external for a policy of forced migration of children that Michael realised he was one of thousands of people it had happened to.

But he also heard about a group who might help him - a UK-based charity named the Child Migrants Trust.

The trust had been set up in 1987 by Dr Margaret Humphreys, a Nottinghamshire social worker, after she began to come across horrific stories of children who were forcibly emigrated from Britain to countries including Australia - often without the knowledge of their birth parents.

A film named Oranges and Sunshine, starring Emily Watson, was made about her work.

Michael learned his mother, Ilse, lost her family in the Holocaust. She came to Australia to try to find him - but never did

Armed with his birth name, his British passport and the few facts he knew of his pre-adoption identity - that he had arrived in Australia on a boat at the age of five, having been moved from an English children's home to an Australian one - Michael approached the trust's office in Perth.

They began the task of trawling the records to try to uncover something about his background.

It turned out the answer had - in some sense - been staring them in the face.

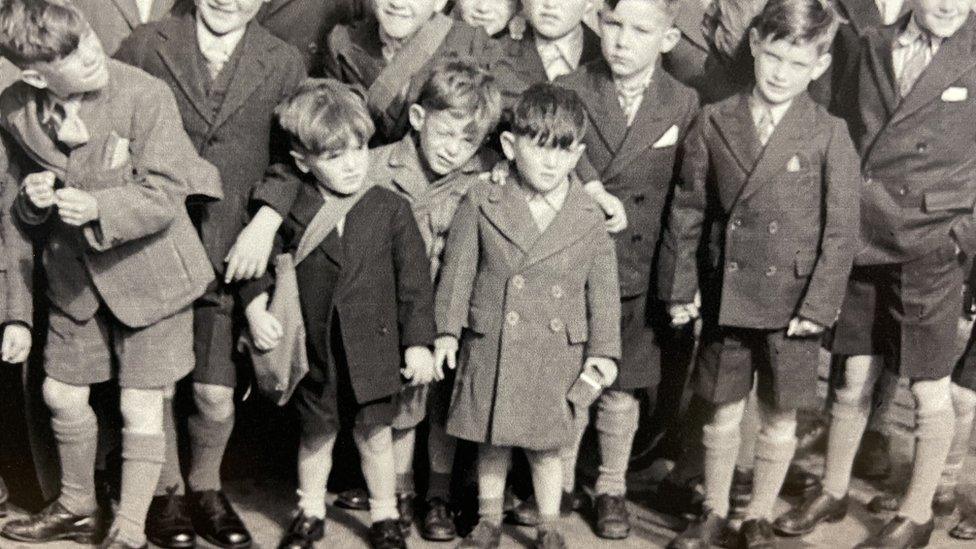

In the office was a picture of a group of children on the deck of a boat in Australia after a long voyage.

They had managed to identify everyone in the picture, apart from the confused and sad-looking little boy with an oversized coat and scuffed shoes who had an arm placed around him by a fellow migrant.

That child, it turned out, was Michael.

Michael had been born Michael Lachmann and - he learned - was of German Jewish descent.

His mother, Ilse, had fled to England via Italy from Nazi Germany in 1939. Her parents and brother, who had remained in Germany, were murdered during the Holocaust.

And, tragically, Michael discovered she had wanted to give him a home.

"I realised that my identity had been stolen," he said.

Michael (centre right) had been sent to Australia at the age of seven

He learned his mother had joined the services in the fight against Hitler. During that time, she had entered into a relationship with a soldier and subsequently fell pregnant.

She had put Michael into the care of a Catholic children's home but in a letter, found by the trust, she stated explicitly she wanted to give her son a home when his father came back from the war.

Dr Humphreys said: "She wrote this very moving letter saying when Michael's father returns from the war, we will collect our darling baby together and we will have him home and have a happy life."

But when she went back to get him, she was told he had been sent to Australia.

Michael travelled to Germany with Margaret Humphreys to find out more about his family

Michael learned his mother had followed him to Australia but had never found him. His name had been changed and he was living in Perth.

Ilse had died in Melbourne in 2009, the year before Michael had gone to the trust for help.

However, the trust has been able to support Michael to explore his family history.

This month he and Dr Humphreys travelled to the city of Chemnitz in Germany, from where his mother fled the Nazis more than eight decades earlier.

"I just felt in my heart it was important for me to come and touch the ground where my mother was," he said.

Michael's uncle Werner - his mother's brother - died in the Holocaust. Michael says his uncle was "the spitting image" of him

There, Michael visited a memorial to his grandparents and uncle on the site of his family's former home.

He later travelled to the Jewish cemetery in Chemnitz.

As he got there, it was bathed in autumn colours and sunshine. He gazed at the tombs of his grandmother's side of the family - the Franks.

"After all these years I can actually see where they are buried. It's wonderful," he said.

In Germany, Michael discovered some of his birth relatives had survived the Holocaust and were living in New York

The city authorities, who were organising a memorial project, invited Michael to view a film they had made which featured members of his German family.

For the first time, he could see the faces of relatives he had never known existed.

"You've been going around for 80 years, not knowing all these people and suddenly you're learning about them," he said.

"It's such a big thing to do... a great experience and emotional as well. You get the closure you need to be able to say 'I found where I belong'."

Thanks to a video call, Michael was able to see his living relatives for the first time

Some of them, he learned from researchers in Chemnitz, had ended up living in New York.

Shortly after finding this out, the trust carried out its first online reunion.

They found an empty office building in the city with a giant TV screen for Michael to see and talk to - for the first time - birth relatives: his New York family.

He learned his great aunt had escaped the Nazis too.

Michael's grandmother died at the hands of the Nazis, but her sister - like his mother - escaped and emigrated

Although she was no longer alive, her daughters and other relatives were all on screen, waiting to greet him.

His voice cracked as he waved and said: "Hello. How are you?"

"Welcome into the family," they replied.

He now hopes to keep in touch with his family and potentially use the travel fund set up by the British government for child migrants and administered by the trust to meet them one day in New York.

"I'd love to meet my family," he said.

"This is the greatest thing I have ever done - the gift that I've got now to be able to say 'This is my roots, this is where I come from, this is where my family came from and I can get to know more about them'."

Michael said he felt very sombre as he contemplated the loss of his birth family, including his grandfather

On his final day in Germany, he went to the Holocaust memorial near the Brandenburg Gate to remember the murdered family he never met.

It is an imposing monument of flat-laid stones.

Even on a warm, sunny day, the towering stones carry a marked chill.

"It makes me sombre. Very sombre," said Michael.

He had one more stop to make on his European journey. It was a trip to Nottingham - home of his late wife's family, who emigrated to Australia through choice.

It was also, by coincidence, the home of the charity that helped him uncover his past and, hopefully give him a new future.

Michael says his travels have given him a legacy

He travelled to a tiny memorial by the banks of the River Trent - a small plaque next to a tree.

This is dedicated to the 10,000 children who were separated from their families by the child migration scheme.

As he looked at it, Michael's thoughts were with his family and his own children and grandchildren.

"They can have this legacy, my legacy," he said.

Follow BBC East Midlands on Facebook, external, on Twitter, external, or on Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to eastmidsnews@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published26 February 2017