Stephanie Slater: The kidnap victim who faced a second ordeal

- Published

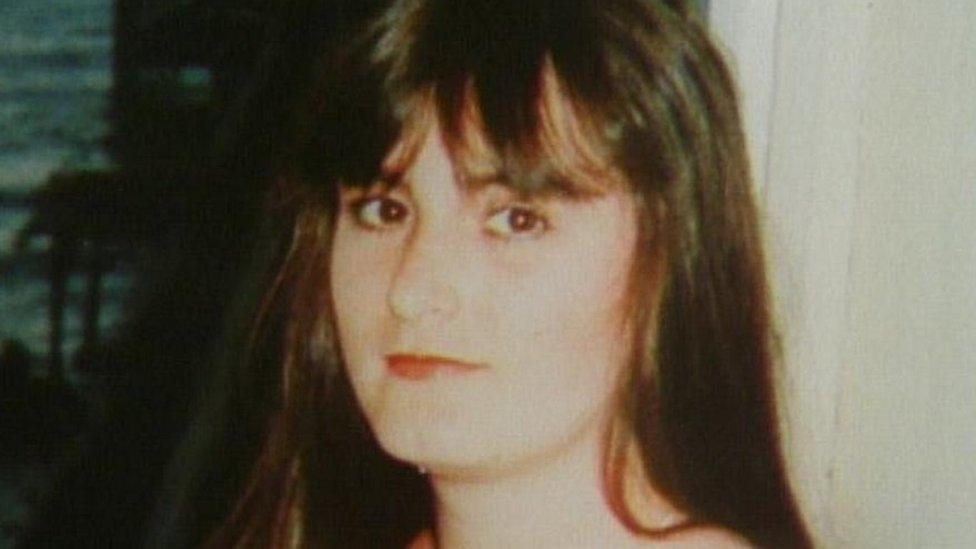

Stephanie Slater was always determined to talk about the case to highlight dangers to women

Held captive for eight days by one of the UK's most notorious kidnappers, Stephanie Slater faced a new trauma in the aftermath of her release. She would go on to have a huge impact on how victims of crime are treated.

In 1992, the 25-year-old was working at a Birmingham estate agents when she was abducted at knifepoint.

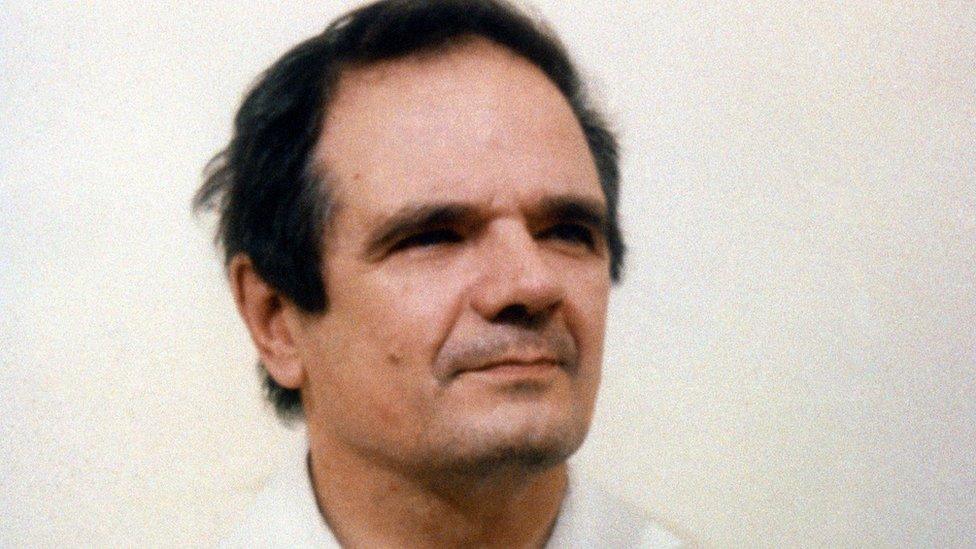

Her kidnapper, Michael Sams, had set a trap, posing as a potential house buyer.

Stephanie endured the horrific ordeal of being kept handcuffed, gagged and blindfolded in a coffin-like box, itself locked inside a wheelie bin in Sams' workshop in Newark-upon-Trent in Nottinghamshire.

Sams, from Sutton-on-Trent, was later found to have murdered 18-year-old Julie Dart from Leeds after using similar means to imprison her.

But remarkably, after eluding a police cordon to pick up a £175,000 ransom from her employers, Sams let Stephanie go.

Julie Dart was killed without any serious attempt to pick up a ransom

During his trial, Stephanie described how she had talked to Sams to try to engage with him and increase her chances of survival.

Speaking in a later interview, Stephanie said: "Don't get me wrong, I was terrified every single time I spoke to him. I thought 'I hope I don't say the wrong thing and make him angry'."

Her evidence helped convict him of not only her kidnap, but also the murder of the Leeds teenager.

In 1995, Stephanie published her own account of the kidnapping - Beyond Fear: My Will to Survive.

At the time, she said: "I wrote the book for women who are in danger and I'm trying to speak out for women who are taken by maniacs like Sams.

"I wanted to speak out, a voice in the wilderness, because nothing seems to be done for women these days, nothing has been done since I was kidnapped."

Sams kept Julie and Stephanie locked in a box in a workshop near the centre of Newark, Nottinghamshire

So how did Stephanie end up working on behalf of women who have been through traumatic crimes and the sometimes harrowing police investigations?

Following her release, Sams took Stephanie home, dropping her two streets from her front door.

"He pulled up the car, he said 'I'm sorry about everything; you were the innocent victim'," she recalled, in a later interview.

"Then he said 'Don't look back at the car'. I fell out on to the pavement and the door shut behind me and he drove off at speed. When I opened my eyes, I was partially blind.

"The pressure of the blindfold for eight days and nights had damaged my eyes. All I could see were the swirling orange street lamps. And I could hardly walk."

Somehow, she staggered back to the home she shared with her parents and rang the bell.

"A guy opened the door and I didn't recognise him," she said. "I thought I had come to the wrong house. It turned out he was my mum and dad's family liaison officer.

"He had been there for eight days but had never seen a photograph of me, so he didn't recognise me. Over his shoulder, my dad appeared and screamed 'It's Stephanie. Stephanie's back' and he hauled me into the porch."

Seeing her father's reaction the officer then, shockingly, blocked her from hugging her parents, due to the risk of contaminating forensic evidence.

Stephanie Slater was initially blocked by police from hugging her parents

In a later interview she recalled: "He pushed me to the back of the room, sat me in a chair and said 'You stay there. Don't touch the arms of the chair. You sit there and don't do anything'.

"I was absolutely terrified. I was thinking 'Dear God, what is going on?'

"The reality of it is, you are back from a terrible ordeal and you see your mum or dad and you want to hold them or hug them.

"To a police officer, you are a walking crime scene - I had fibres and things all stuck to me and whatever else.

"But I should never have been denied just a hold of a hand to know that I was home."

The kidnapping of Stephanie Slater

A seven-part podcast on the Stephanie Slater case is available on BBC Sounds.

Best friend Stacey Kettner said Stephanie confided in her about what happened next.

"The room was cleared and a police surgeon, or whoever they called, made her get undressed in her own living room on this big sheet of brown paper," Stacey said.

"I remember that the door from their living room had frosted glass, so she could see there were people on the other side of that door, so she felt exposed.

"She had long hair and it was matted.

"[The police] had a kind of tick sheet and the doctor was going 'Right, take some blood'.

"There was no empathy, it was kind of 'Right, next thing' - they pulled some hair out without saying that it was what going to happen.

"They took her hand and cut her nails - nothing was explained to her, there was no gentleness."

Stephanie felt upset at the way the police handled her case but later worked closely with forces to try to improve their treatment of women

On top of this, a deal struck between the police and media not to publish details of the kidnap meant Stephanie was put in front of a press conference less than 12 hours after being released and before she had been officially interviewed by officers.

While Stephanie mostly co-operated with police, giving dozens of statements, she refused one suggestion - to re-enact her kidnapping to see if it would jog her memory of events.

Stacey said the psychological strain of Stephanie's ordeal, and a wish to protect her mother, led to her initially not telling police she had been raped by Sams.

Through all of this she did not have any counselling, leaving her and her family to deal with the aftermath alone.

She fled to the Isle of Wight, and for a while a "broken" Stephanie struggled with building a new life.

However, being introduced to a police officer unexpectedly led to a new role.

Stacey recalled: "He was like 'Oh gosh it would have been so interesting during training to talk to someone, or hear about this from someone who has experienced this'.

"He asked if she would be interested in talking to some police trainees and she said 'That's fine'.

"It all started from there."

Stephanie found her work with the police gave her a sense of purpose after her ordeal

Within months she had started doing presentations and seminars about the treatment of victims of crime.

"The police loved her," said Stacey. "People who have gone through situations like that, they so rarely come back alive.

"It gave her a sense of purpose, it was a tonic for her."

Stephanie described it as "the counselling I never had".

Stephanie confided in best friend Stacey Kettner the trauma of both the kidnapping and police investigation

Tanya Bridgeman, former vice chair for Stalking and Harassment for the Association of Chief Police Officers, described the impact of these sessions.

"The whole room, you could have just dropped a pin in the whole time," she said.

"She presented the effect of the investigation afterwards and how really that was the thing that took the longest to get over.

"After that, officers just wanted to improve the way they worked and kept asking for more training when she came.

"Now there is an understanding there has to be a balance between [collecting] evidence and, more than anything else, the welfare of that victim."

Who was Michael Sams?

Sams set out complex instructions for picking up the ransoms - and succeeded in getting £175,000

Sams, a 49-year-old heating engineer who had been in prison for theft, kidnapped Julie Dart from the Chapeltown area of Leeds on 9 July 1991.

Notes from Julie, along with ransom demands and wider threats, were sent to police, as well as complex instructions to pick up messages from locations like public call boxes or country lanes.

None resulted in cash being handed over. It later transpired Sams had beaten Julie to death.

After kidnapping and releasing Stephanie Slater a few months later, Sams was caught when his first wife recognised his voice from a clip played on BBC's Crimewatch.

Stephanie died of cancer aged 50 in 2017.

Despite her work, recent cases such as the killings of Zara Aleena, Sabina Nessa and Sarah Everard have highlighted the fact that women remain far from safe as they go about their daily lives.

The family of Suzy Lamplugh, who, like Stephanie, is believed to have been kidnapped during the course of her work as an estate agent, has long campaigned on the issue.

Suzy's brother, Richard, works alongside the Suzy Lamplugh Trust and feels progress on safety since Stephanie's abduction has been mixed.

Campaigners say progress on women's safety since Stephanie's kidnapping has been mixed - as highlighted by the case of Sarah Everard

"Today there is a lot more surveillance and more legislation but it hasn't stopped men doing this, which you would have hoped they would," he said.

"But there must be something that keeps men, in particular, wanting to do this sort of thing, which is terrible.

"I've always said I wish we could wind the trust up but it's still needed out there."

Sams remains in prison after being jailed for life in 1993. He has twice being turned down for parole, most recently in 2022.

Follow BBC East Midlands on Facebook, external, on Twitter, external, or on Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to eastmidsnews@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published25 November 2022

- Published18 November 2022

- Published1 October 2022

- Published3 March 2022

- Published1 September 2017

- Published1 March 2012