West Burton A - the past and the future of power?

- Published

Is the sun setting, or rising, on the immense West Burton power station?

On Friday, one of the country's last coal-fired power stations - West Burton A - closed for good.

It stands in "Megawatt Valley", near the River Trent, where the cooling towers of 14 power stations once dominated the landscape.

These stations used to provide up to a quarter of the electricity supply of England and Wales but only one of them - Ratcliffe-on-Soar some 40 miles (65km) to the south - remains operational as last of its kind in England.

West Burton A was slated to close last year but was kept going by the government to provide emergency reserve capacity over winter.

So why is the huge West Burton A facility, still apparently of use to the UK's energy supply, being decommissioned - and what will keep the lights on once it is gone?

Coal-fired power stations, including Cottam (foreground) and West Burton A, once dominated the Trent Valley - and provided immense amounts of electricity

Prof Aoife Foley, chair in Net Zero at the University of Manchester, said the miners' strike of the mid-1980s marked the beginning of the end for "King Coal".

She said: "British coal was seen as too expensive and too unionised - so it was easier and cheaper to import it.

"That - and emerging awareness of emissions and climate change - prompted the 90s 'Dash for Gas' which was cheaper, cleaner and more efficient."

In 1951, 98% of UK electricity was generated by coal.

Even in 1990 the figure was 65% and by 2010 a still substantial 40%.

By 2021 however, only 2.9% of UK electricity came from coal.

West Burton at night

West Burton A: Powerful legacy

Start of construction: 1961

Start of generation: 1966

Units: 4 with 4 turbines with max capacity of 2,000MW

Coal train deliveries through lifespan: 165,000

Total length of those trains if put end to end: 41,250 miles (enough to go more than one and a half times around the world)

Coal stockpile at peak operation: 2.25million tonnes

Total generation over lifespan: 491,789 GWh (enough to run a 2 bar electric fire for 26,596,646 years)

Lifespan running time: 1,130,407 hours

Coal used during lifespan: 194,700,000 tonnes (135,000 tonnes per week at capacity)

End of generation: March 2023

Source: EDF

But the march to cut carbon emissions stumbled with the war in Ukraine and subsequent energy crisis, which saw cheap Russian gas supplies turned off, bills soar and talk of widespread power cuts.

Into the breach came West Burton A which, along with Ratcliffe-on-Soar and Kilroot in County Antrim, Northern Ireland, had its life extended by six months to act as a stand-by to handle peak demand if other sources were insufficient.

In the event, of the three emergency coal power plants fired up for the cold snap, only West Burton A was used and just for a few hours, on 7 March.

Despite this, the government wanted owners EDF to keep the plant operational for next winter - a request the company declined due to the demands of staffing and maintenance.

Until Friday, 117 EDF staff were keeping West Burton going but the company said that number will be phased down as the plant is decommissioned through the rest of 2023.

EDF said a small team of six would remain by January 2024 when the process of razing the entire site to the ground will begin.

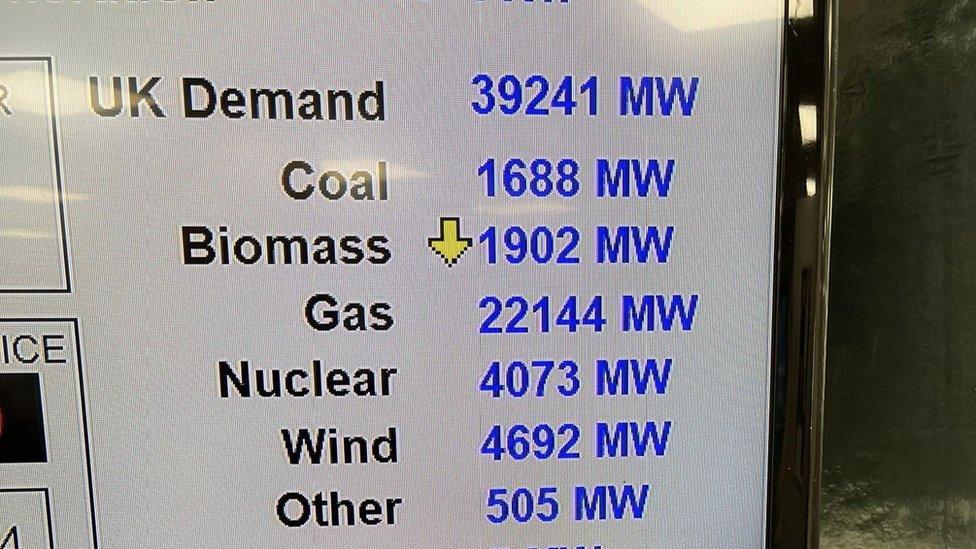

On 7 March, for the first time in months, West Burton A was called on to supplement national power demand

So how is the UK going to cope without coal?

Prof Foley said: "We need three types of power - baseload, intermediate and peak - and energy supplies which can meet those.

"Baseload is the stuff we need all the time, from hospitals to fridges, intermediate is the main daytime demand, and then peak is the cooking, heating and tv in the evening.

"Renewables can provide lots of power but can't be guaranteed due to the vagaries of weather and climate change unknown.

"So it's a question how to meet those demands, and for the scale of demand in the UK, nuclear guarantees very low carbon generation to ensure energy and grid security."

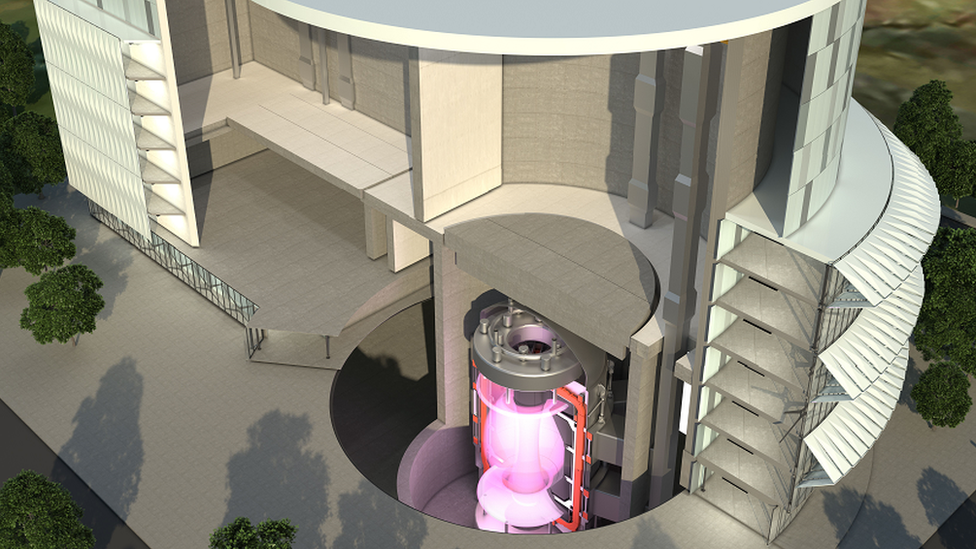

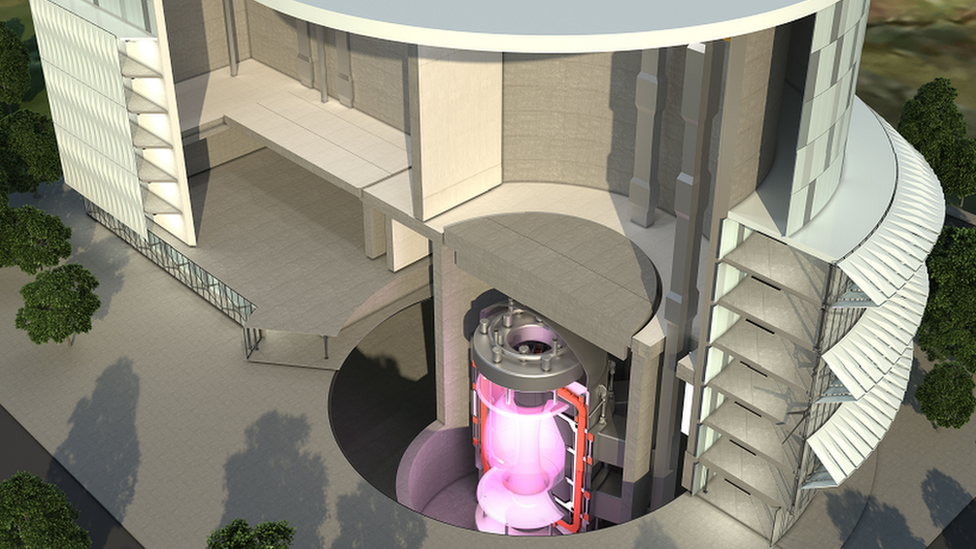

Perhaps the answer is a power station at West Burton after all - just not the one we have at the moment.

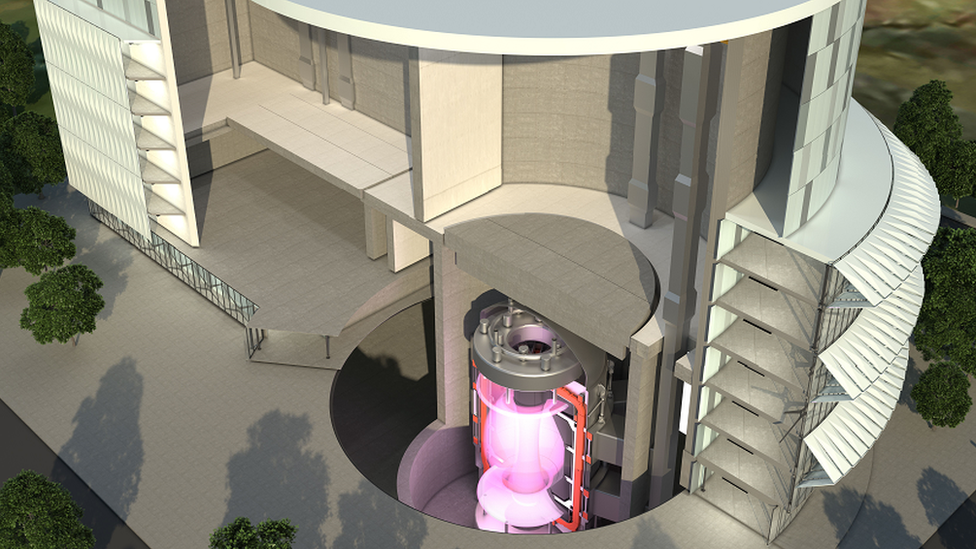

In October the government announced the UK's first prototype fusion energy power plant would be built on the site.

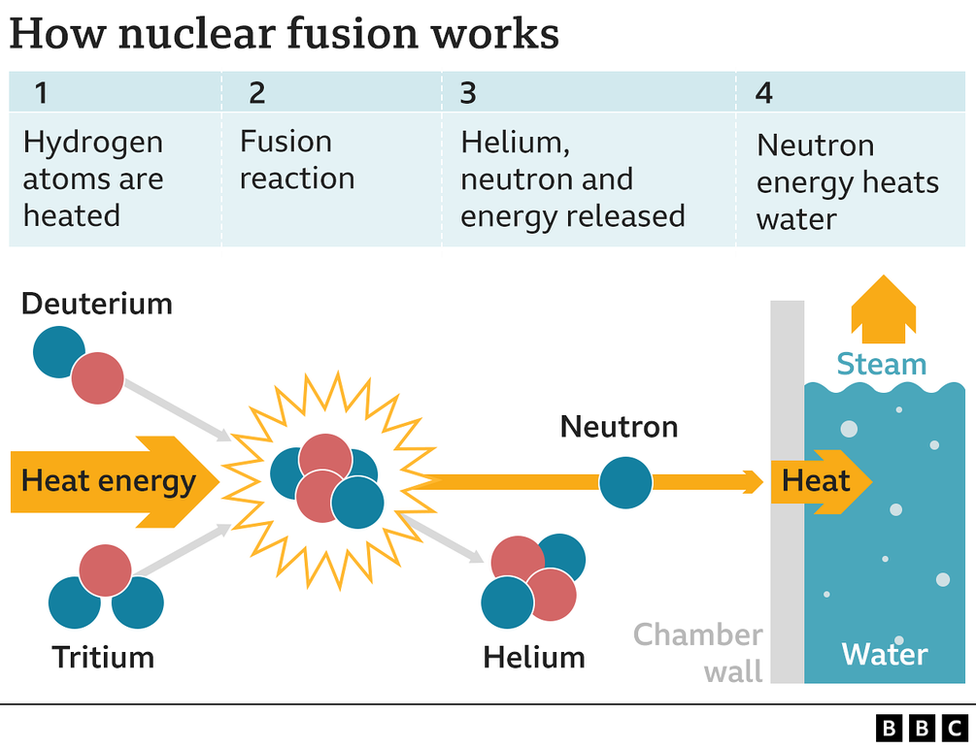

Nuclear fusion can produce large amounts of power with little fuel, waste or risk of accidents

Why develop nuclear fusion?

No carbon emissions: The only by-products are small amounts of helium, an inert gas which can be safely released without harming the environment.

Abundant fuels: Deuterium can be extracted from water.

Energy efficiency: One kg (2.2lb) of fusion fuel could provide the same amount of energy as 10 million kgs (9,842 tons) of fossil fuel.

Safer waste: There is no radioactive waste by-product from the fusion reaction.

Safety: The fusion process is difficult to start and keep going, so there is no risk of a runaway reaction leading to meltdown.

Reliable power: Fusion power plants will be designed to produce a continuous supply of large amounts of electricity.

Source: UK Atomic Energy Authority

At the time of the announcement, EDF's plant manager for West Burton Andy Powell said: "Moving from fossil to fusion technology is an exciting prospect that connects directly to the company's purpose, to help Britain achieve net zero. This scheme will also secure jobs in the local area for decades to come.

"Our commitment in securing a just transition for the workforce and communities connected to coal has now been realised and I can't wait to see it all come to life."

But is fusion - still in the experimental stage - really likely to give us the power we need without coal? And if so, when?

Prof Martin Freer, director of the Birmingham Energy Institute, described coal as a "miserable, dirty and polluting" form of energy.

But while he welcomed the phasing out of coal-fired power stations, he warned a predicted surge in demand for electricity poses big challenges.

More electric vehicles will increase the demand for power in in the future

He said: "With the rise in EV use, along with the likely shift to heating homes with heat pumps rather than gas, the demand for electricity is likely to double, but it could be three or four times greater.

"That leaves us in a very bad place as far as the necessary energy generation goes".

He backs investing in a wide range low carbon power technologies to see which "lasts the course".

But he also admitted the unpredictable nature of renewables demand "energy storage solutions that at the moment we simply don't have".

So is fusion the answer?

Ultimately, the process would be used to drive steam turbines to generate electricity

Prof Freer said: "Nature can do this rather simply - it is what happens in stars due to the vast gravitational forces - but it's much harder on a small scale on earth.

"The problem is how to heat and contain the plasma and then how to get useful energy out.

"But there has been a lot of progress, the basic principles are now reasonably well understood.

"Fusion has gone from being a science experiment and has transitioned into an engineering challenge. The mentality has changed."

Prof Freer believes while a target date of 2040 for commercial fusion is "optimistic", West Burton presents a unique opportunity for the UK as a whole, but also the region in particular.

Fusion module being assembled at the international project Iter in southern France, in January 2023

"West Burton is where is it because it needed the coalfields," he said.

"Now those are gone but there is no need to say to people 'That's it, time to go somewhere else'.

"Fusion is taking those jobs and transitioning them into new jobs and there will be a colossal amount of investment here.

"This will be a beacon and it could change the face of this part of the Midlands for decades to come," he says.

Prof Foley shares this belief, saying: "Calder Hall in the UK was the world's first commercial scale nuclear station in 1956.

"The UK innovates and this nuclear fusion project at West Burton demonstrates the UK's commitment to energy security, the economy and net zero."

Follow BBC East Midlands on Facebook, external, on Twitter, external, or on Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to eastmidsnews@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published30 March 2023

- Published3 May 2024

- Published7 March 2023

- Published13 January 2023

- Published14 December 2022

- Published6 October 2022

- Published3 October 2022