Nuclear waste removal begins 30 years after power station closure

- Published

Berkeley power station closed in 1989 but it has only now been safe to remove its nuclear waste

Work has begun on removing nuclear waste from Berkeley power station, 30 years after it was decommissioned.

The disused Magnox generator, situated on the banks of the River Severn in Gloucestershire, closed in 1989.

It was one of the world's first commercial nuclear power stations and its laboratories and many of its buildings have already been dismantled.

Work emptying its vast concrete vaults of the nuclear waste Berkeley generated is only now able to safely begin.

But it will not be safe for humans to go inside its reactor cores until 2074.

The BBC has been given a rare glimpse of what is stored under the disused site.

The estimated cost of decommissioning of Berkeley is £1.2bn

For the past 50 years parts of the coastline of the west of England have been dominated by nuclear power stations.

The 1960s saw the construction of Hinkley A and Hinkley B in Somerset, with both Oldbury and Berkeley built on the banks of the River Severn in the 1950s.

Only Hinkley B is still in use but the nuclear waste the stations generated has remained in place.

It takes hundreds of years to decompose and has to be stored underground.

It will cost an estimated £1.2bn to fully decommission Berkeley.

About 200 people are currently working on the site under strict security.

Work emptying waste products from the concrete vaults, eight metres (26ft) underground, is a complicated process.

They contain used graphite from the fuel elements in the nuclear generating process, material from the cooling ponds and from the laboratories.

The removal is expected to take five or six years to complete.

Rob Ledger is in charge of waste operations during the decommissioning process

Rob Ledger, waste operations director at Berkeley, said: "When the power stations first started generating I don't think there was much thought put into how the waste was going to be dealt with or retrieved.

"It's taken a while to develop the equipment and the facilities [to do this].

"A mechanical arm moves the debris into position and then a 'grab' comes down through an aperture in the vaults and picks up the debris [and] puts it into a tray.

"Each debris-filled tray weighs up to 100kg (220lb).

"The automated machinery is controlled by computers [and] tips [the waste] into a cast iron container."

The mechanised process to extract nuclear waste is happening eight metres underground

The containers will house the waste in an intermediate storage facility until a long-term solution can be found.

"Nuclear waste does take a long time to decay... it's hundreds of years. And that's why we have to go to these lengths, to store it safely," said Mr Ledger.

Eventually the boxes will be housed deep underground in a long-term storage facility. The location has not yet been decided by the government.

The Intermediate Storage Facility (ISF) at Berkeley will house cast iron containers of nuclear waste until a long-term solution is decided

There are currently estimated to be almost 95,000 tonnes of nuclear waste in the form of graphite blocks across the UK.

But if the Carbon 14 can be extracted from the blocks, they become much safer and easier to deal with.

A new process is being explored, by scientists at Bristol University, to ensure not all of the waste will be discarded.

They have developed a process that uses reactor core spent contents in a new power form.

Carbon 14 from nuclear reactors is infused into wafer-thin diamonds, man-made in a lab at Bristol University.

They then become radioactive and form the heart of a battery that would last for many thousands of years.

You may also be interested in:

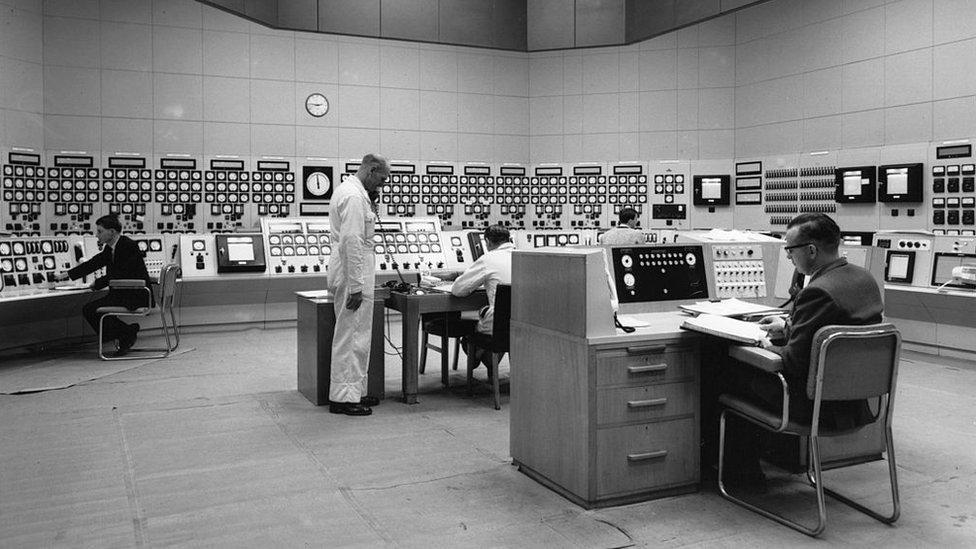

Berkeley, seen here in 1963, was stripped of its equipment when it closed in 1989

The tiny batteries could be used in pacemakers, hearing aids or sent into space as part of the space programme.

The process is being piloted in association with the UK Atomic Energy Authority in Abingdon.

It is hoped the decommissioned Gloucestershire site may be redeveloped to manufacture the new batteries, creating jobs in the region.

- Published17 January 2019

- Published15 December 2010

- Published19 March 2013