Coronavirus: Astronaut Helen Sharman shares isolation coping strategies

- Published

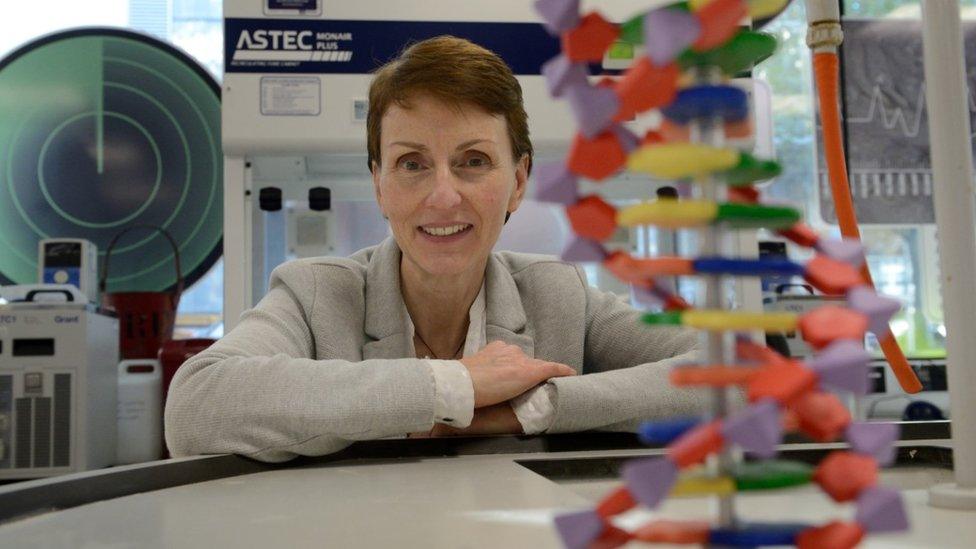

Helen Sharman spent eight days in space in May 1991

Astronauts know better than most how to cope with isolation - something many people are now dealing with. As coronavirus restrictions are extended in the UK, can we learn any lessons from space travel?

Dr Helen Sharman, a scientist from Sheffield, became the first British astronaut in 1991.

Her time in space may have only lasted eight days but before that she spent 18 months a long way from home in intense preparations at the Soviet cosmonaut training camp Star City.

Stargazing, video-calling loved ones and dreaming of the future were all coping strategies people could make use of, she told the BBC.

The scientist, who now works at Imperial College London, visited the Soviet Mir space station in 1991

Many of the methods she used to get through her time in space, nearly three decades ago, are being echoed now, as - like most people - the 56-year-old spends more time than usual at home. For Dr Sharman, that is in west London.

"The main difference is that [in space] we had some element of choice that we went there, we chose our isolation, but nonetheless we were with our crewmates in a small environment and not able to go out when we wanted," she said.

"Think about what you can do, rather than what you can't," said Dr Sharman, who became the first woman to visit the space station Mir.

"Astronauts prepare themselves to be isolated on a space station but, back in 1991, we only had a radio to communicate, there was no satellite phone, no email.

"Now we have all these ways to keep in touch with people, and it's so important that we use them."

Dr Sharman spent 18 months being trained in the USSR before heading into space alongside two Soviet colleagues

Dr Sharman, who now works at Imperial College, London, said she had adapted like so many to working at home.

"We are all being more tolerant of each other's circumstances," she said.

"We don't have to be in the office, in a dress or a shirt and tie, we can be more flexible."

She stressed that feeling useful was important to people, both in space and on Earth.

"I was grateful to have a busy working day because it made me feel useful," she said. "If suddenly our work diminishes and our days become less busy, we can feel at a loss."

The 56-year-old was the first Briton in space

Being useful could come in the form of reaching out to others who were self-isolating, perhaps, or being able to work from home.

Dr Sharman has spent time doing things she has never had time for before - such as reading a bedtime story online for OSO Arts Centre, external, not far from where she lives.

"I didn't previously have the time to do it but now I can feel as if I am providing a service," she said.

Another coping strategy she suggested was to appreciate nature, something many people seem to be doing with their unexpected free time at the moment.

"I find now I am looking outside my window much more than I did before," Dr Sharman said.

"I can see the houses on the other side of the road, a tree about to burst into flower. I look at the clouds and appreciate the beauty of nature."

"We all see that same moon," said Dr Sharman - and a supermoon lit up the skies over the UK last week

Looking at the stars, has also made her feel connected to distant friends and relatives.

"Then I was looking down at the clouds, now it is up, but it is just that appreciation of the world outside my window. We are all in it," she said.

"If we look into the night sky, we can all see that same moon. That is a nice uniting concept - the stars in the Northern Hemisphere all look the same.

"We can appreciate that all our relatives are seeing that same view that we are."

Dr Sharman appreciates living in a confined space with other people may have its challenges.

She said it "requires a bit more respect and tolerance than normal to maintain cordial relations", something many people who share homes may understand.

"We need to understand each other's frustrations, what annoys us and what helps us to relax," she said. "And it helps if the grotty jobs are shared (tasks like compacting the solid toilet waste and changing air filters are done on rotation in space)."

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

LOOK-UP TOOL: Check cases in your area

MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

Making plans for your free time can be another way to stay sane in isolation, Dr Sharman said.

"One of the luxuries astronauts enjoy is scheduled free time. Earth-gazing, books and films figure highly," she said.

"Now, Covid-19 means we can do some of the things we have always wanted to do but were previously too busy for.

"And we can plan something nice to look forward to because this will not last for ever."

Looking at how the pandemic may change society, Dr Sharman said when she was in space, she did not once think about her possessions and on returning to Earth had a different view on materialism.

"Being less of a consumer society will benefit the environment and reserve resources for what we really need, but I think we will feel the change in society that will be more communal, more cohesive and generally nicer," she said.

"When the pandemic is over, the world will be a better place to live in."

Helen Sharman has previously spoken about her isolation tips to the Royal Society of Chemistry, external.

Follow BBC Yorkshire on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to yorkslincs.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published31 March 2020

- Published6 January 2020

- Published15 December 2015