Miners' Strike: 'We should remember where it all began'

- Published

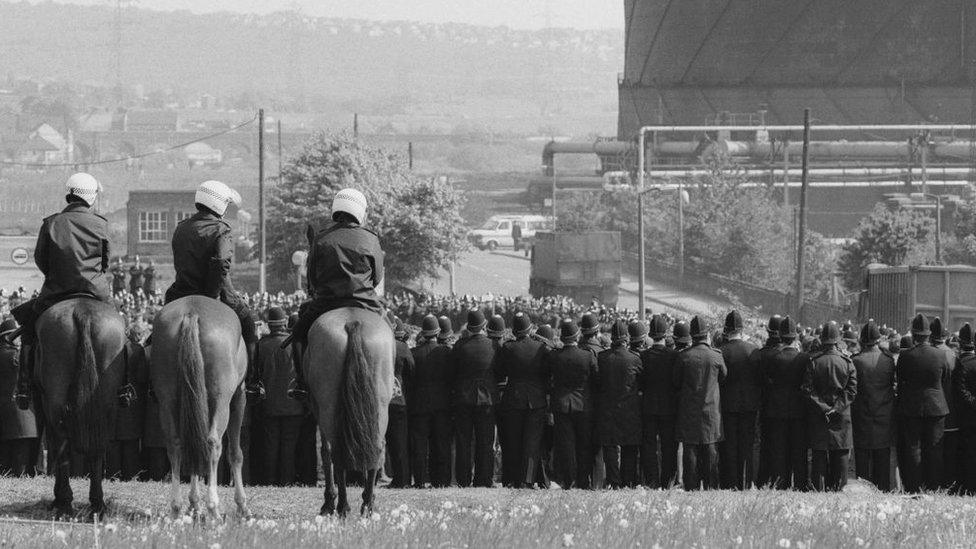

The pit covered a large area on the border of Barnsley and Rotherham

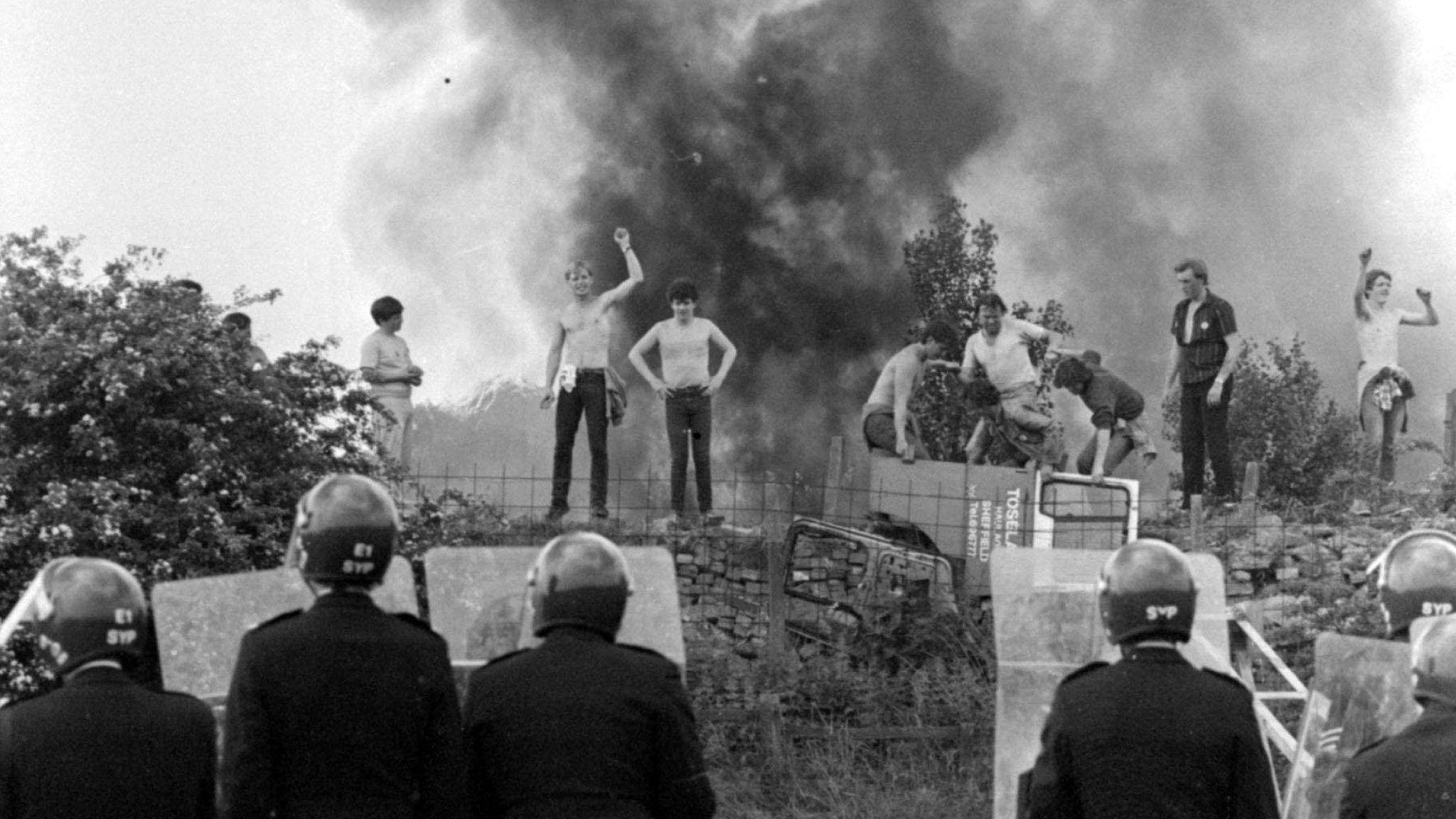

Cortonwood is a name forever etched in history after the proposed closure of the colliery prompted a walkout which eventually led to the 1984 miners' strike.

However, all that remains of the South Yorkshire pit that sparked the biggest industrial dispute in post-war Britain is a spoil heap rising behind a retail park.

On the 40th anniversary of the start of the strike, the BBC has gone back to where it all began.

"I didn't know it was a colliery until I started working here," toy shop worker Danielle Haines tells me.

The 39-year-old, who was born shortly after the strike started, has worked on the site for about 10 years but was surprised to learn the colliery's railway lines once ran across the front of where her employer's shop now sits in the north end of the car park.

"I think it's important people do know [about it]," she says.

"Mining was a big part of life growing up back then, it is important we remember it."

Cortonwood is now best known for shopping, rather than the colliery that was here for more than 100 years

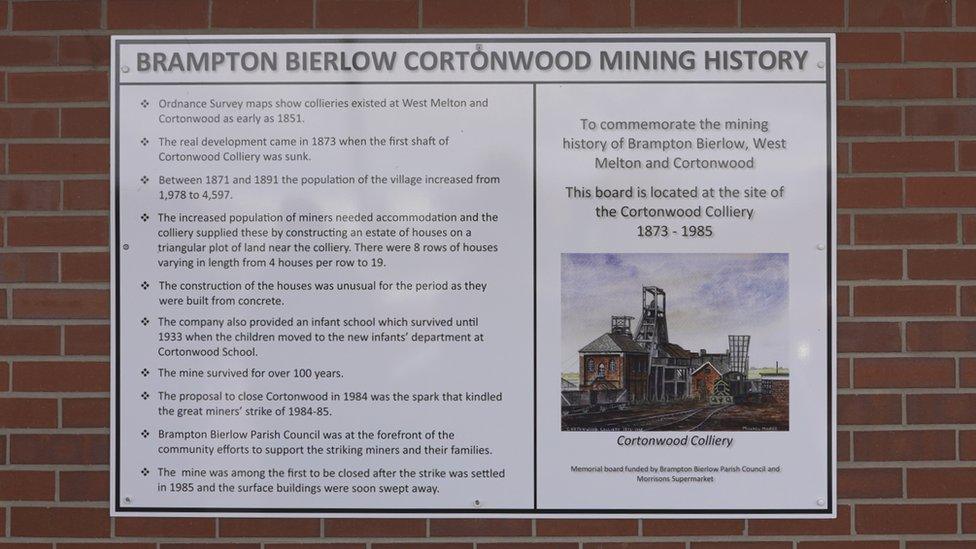

The only clue to it being the once beating heart of the mining community is a sign on the wall of a Morrisons supermarket.

Once a grimy, industrial scene surrounded by deafening noises, Cortonwood, on the border of Barnsley and Rotherham, is now a place for people to shop and relax.

B&Q, Matalan and a Halfords sit above the pit, which was sunk hundreds of metres underground.

The only sign that refers to what the site used to be, placed on a wall of the Morrisons supermarket

Pete, from nearby Barnsley, has been in Argos to buy a battery bank for his phone. He has no idea the pit heads once stood proud in what is now the car park.

"I think it's big to someone who was a miner, but it's nothing really to me," he says.

David Brown, on the other hand, is fully aware of the history. His father was an engineer at the pit for a long time, but is content at the idea of allowing the memories to fade away.

"The only thing you see is the remains of the pit tip and that's about it," he says, gesturing to a hill bathed in sunshine behind him.

"I don't think the site needs any form of commemoration," he says.

"It's an incident in British history, but I wouldn't say it's one that goes down well with everybody."

Don and Jackie Keating, pictured here on the site of the former colliery

The national strike is widely considered to have begun here and it was miners like Don Keating, now 77, who were right in the middle of it.

He used to make the 10-minute, half-a-mile walk each day from his house in Brampton Bierlow, down Knollbeck Lane, and onto the informally known "Pit Lane".

It is not on any maps, but this was where thousands of men walked to work every day.

At the height of the strikes, small wooden cabins stood near to where we talked and it was nicknamed The Alamo. Now, it is a shortcut for shoppers.

A picket line shelter at the end of Pit Lane, once the main road towards Cortonwood Colliery, known as The Alamo

"Sometimes I'm a bit bemused that there's not something down there that commemorates the fact this is where the strike started, apart from the small plaque," he says, as we make the walk he would have made thousands of times before.

"The younger ones, my nieces, they don't know anything about the pits. I'm not saying they should, but in time things just disappear, don't they?"

Thousands of people continue to be employed on the same spot, but in shops and restaurants.

Mr Keating's wife Jackie tells me that "more people work here now than when it was a pit".

But they both agree that the history should be remembered, even if it is only by way a small memorial near the entrance to the park.

"It's a natural evolvement of social history," Mr Keating says.

"It's sad that it happened and it was a massive thing, but there's been a lot larger incidents in history and even they're forgotten."

Follow BBC Yorkshire on Facebook, external, X (formerly Twitter), external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to yorkslincs.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published4 March 2024

- Published3 March 2024

- Published1 March 2024