Miners' strike 1984: Why UK miners walked out and how it ended

- Published

Miners and police clash during a strike at Tilmanstone Colliery in Kent in September 1984

The miners' strike of 1984-85 was a defining moment in the history of British coal mining and the biggest industrial dispute in post-war Britain.

It pitted thousands of miners and their trade union against then prime minister Margaret Thatcher and her Conservative government, which supported plans to shut 20 coal pits.

What was the 1984 miners' strike and why was it important?

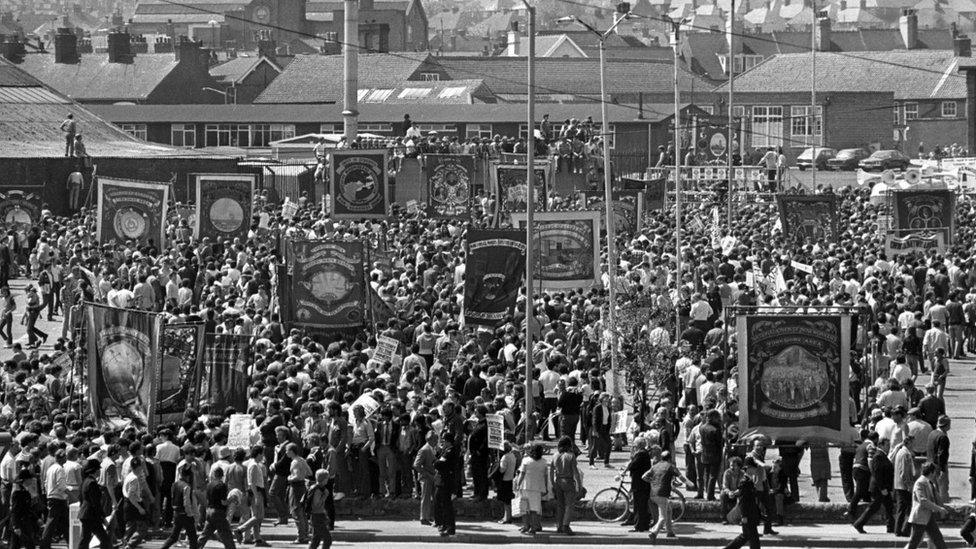

A mass rally of striking miners and their supporters was held in Mansfield, Nottinghamshire, in May 1984

About three-quarters of the country's 187,000 miners went on strike to oppose the pit closures, which were expected to mean 20,000 job losses.

Thousands of officers were drafted in to police the picket lines, with violence breaking out at times.

The miners' eventual defeat was the end of an era for Britain's trade union movement and helped cement Mrs Thatcher's reputation as the Iron Lady.

It paved the way for the privatisation of more nationalised industries and utilities, including steel, railways, gas, telecoms and water.

A wave of pit closures followed the strike and almost all of the UK's deep coal mines - where digging takes place underground - were shut within the next 20 years.

It caused lasting unemployment and poverty in former mining areas, just as the workers had warned with their slogan "Close a pit, kill a community".

In 2019, Sheffield Hallam University researchers said the former coalfield areas - with a combined population of 5.7 million people - continue to be dogged by deprivation and poor health.

What caused the strike and how did it begin?

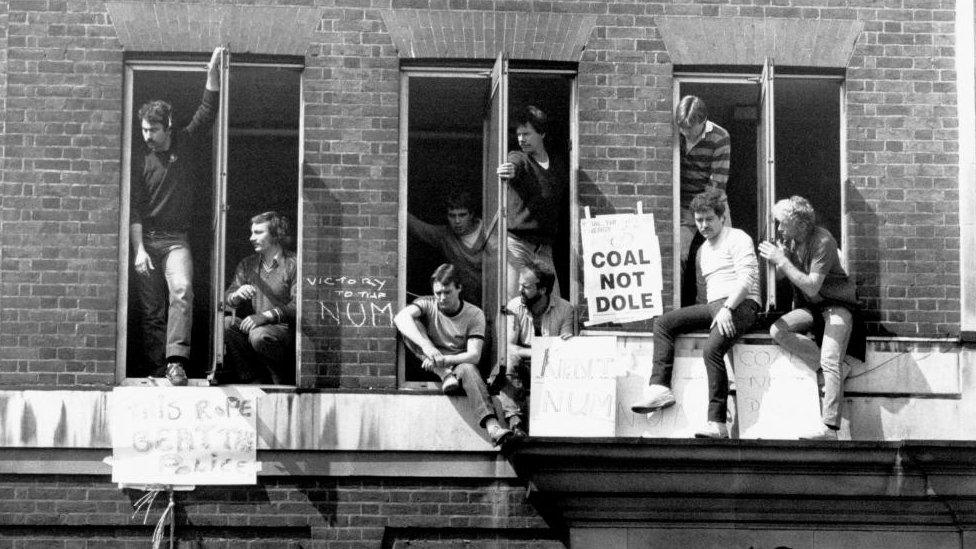

The Coal Not Dole slogan was popular among those who argued subsidising unprofitable mines was less costly than paying benefits to unemployed miners

The National Coal Board (NCB) ran the country's collieries - coal mines or pits and their buildings - and distributed coal. It wanted to close 20 pits it said were unprofitable.

Former miner Arthur Scargill, then president of the National Union of Mineworkers, external (NUM), believed no pit should close if it had coal reserves. He claimed there was a plan for more than 70 closures, something only confirmed in 2014 when old cabinet papers were released.

The national strike is widely considered to have begun at Cortonwood Colliery in South Yorkshire on 5 March 1984 after miners learned the NCB wanted to speed up plans to close their pit. Two weeks earlier, miners at Polmaise Colliery in Stirlingshire had also gone on strike to oppose pit closures.

Walkouts followed elsewhere and the NUM declared a national strike on 12 March 1984, despite having held no national vote.

The High Court ruled the strike was illegal in October 1984 because it had not followed NUM rules, although the Scottish High Court had ruled it was legal in Scotland the previous month.

Where did miners strike?

Policemen dividing the two factions involved in a Right To Work rally by miners at the Nottinghamshire NUM headquarters in May 1984

The majority of miners in England, Wales and Scotland walked out, but some kept working because they disagreed with the NUM's position.

Robert Gildea, emeritus professor of modern history at the University of Oxford, said: "Areas at risk of losing more pits were more liable to strike. The small Kent coalfield was destined for total closure. South Wales and Scotland would lose two-thirds of their pits.

"Nottinghamshire, by contrast, was spared. This was partly because the pits were seen to be more efficient, and partly to divide the miners."

Even when national support was at its highest, most of Nottinghamshire's 30,000 miners kept working and long-lasting community divisions were created.

Professor David Howell, who teaches politics at the University of York, said many of the Nottinghamshire miners were focused on their area rather than any wider solidarity.

"Their pit culture was characterised by co-operation with management in pursuit of high productivity and high earnings underpinned by optimism about future employment," he said.

How did Margaret Thatcher's government respond?

The strike was often characterised as a battle of wills between Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and NUM president Arthur Scargill

Mrs Thatcher had seen how miners' strikes in 1972 and 1974 caused blackouts as power stations were left without fuel, undermining the governments of the day.

She was determined to win any battle with the miners and had prepared meticulously for a potential strike, including stockpiling six months' worth of coal to keep the country's power stations running.

The government had previously introduced anti-strike legislation and told police to stop pickets from intimidating miners who wanted to work.

When Mrs Thatcher died in 2013, NUM secretary Chris Kitchen said he would not shed a tear for someone responsible for "vindictive acts" towards mining communities.

What role did police have and how many people were arrested?

Officers were drafted in from all over the country to police the picket lines

The National Reporting Centre was set up to co-ordinate police operations and extra officers were drafted in from forces nationwide.

More than 11,000 people were arrested - mostly for public order offences - and more than 8,000 prosecuted. Arrested miners were likely to lose their jobs and some never worked again.

In 2020, the Scottish government said it would pardon convicted miners after a review found it was unlikely many would have been prosecuted today.

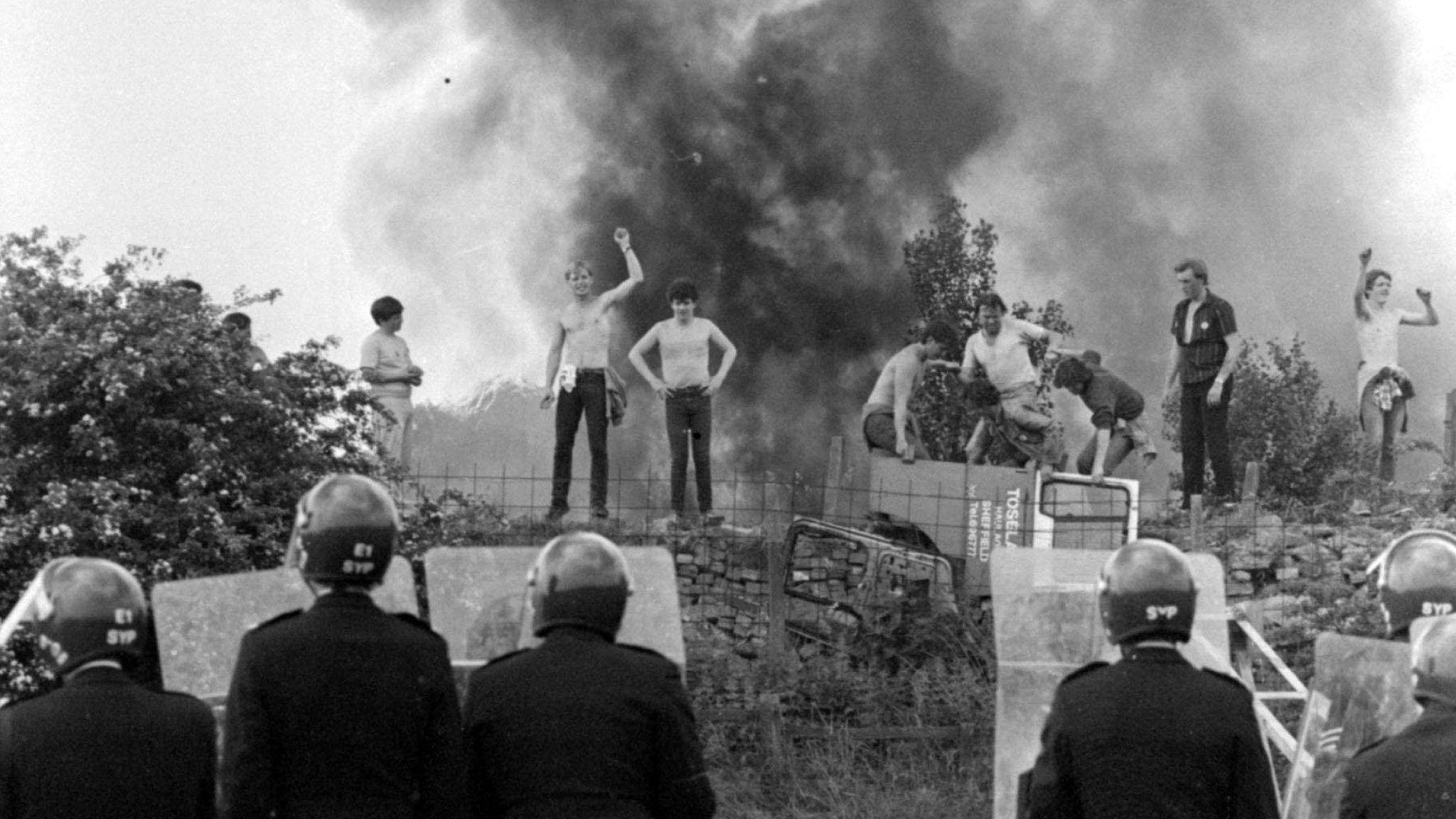

There are also continuing calls for a public inquiry into the actions of police during a violent clash known as the Battle of Orgreave.

On 18 June 1984, around 6,000 officers with dogs and horses confronted an equal or higher number of pickets outside the coking plant in Orgreave, South Yorkshire. Ninety-five pickets were arrested and later acquitted.

How did the strike end and what happened to the mines?

Women walk past Cortonwood Colliery with banners flying on the day before the miners returned to work

Union funds were running low by early 1985 and striking miners had endured almost a year of hardship, with only donations to support their families.

With some miners still working and police protecting coal deliveries, the union's position was weakened.

When the NUM held a special conference on 3 March 1985, coalfield delegates narrowly voted to end the strike. Miners returned to work on 5 March.

The closures prompting the strike were just the start, with many more over the next decade. They included 32 announced in 1992 as natural gas became the fuel of choice for power stations.

Sheffield Hallam University, external estimated the UK coal industry had a total workforce of 221,000 at the time of the strike but fewer than 7,000 by March 2005.

Kellingley Colliery in North Yorkshire, the UK's last deep coal mine, closed in December 2015.

Workers completing the final shift at Kellingley Colliery as it closed on 18 December 2015

Related topics

- Published3 March 2024

- Published18 February 2024

- Published11 February 2024

- Published29 January 2023

- Published1 October 2022