Lockington Crescent: 'We camped in our cars to buy a house'

- Published

Dozens of people queued in cars for days to secure a property on the new estate in Suffolk

Buying a house in 2019 more often than not requires a deposit running into tens of thousands of pounds. But in Stowmarket in 1972, some prospective homeowners were able to put down just £50 - and went to great lengths to do so.

"It was worth it in the long run," says Sue Petty, who has never moved from the house she snapped up in Lockington Crescent some 47 years ago.

"Everybody was friendly because we were all out there for the same aim. We were all youngsters - we had a laugh and a glass of wine."

The 67-year-old was one of dozens of people who queued for days to secure a property on the new estate in the market town in Suffolk. The houses, bungalows and 64 plots in the crescent and the yet-to-be-built Danescourt Avenue went on sale at 09:30 BST on 8 April 1972.

But at the end of March, a line of cars started to appear outside the office of developer Laurence Homes. And for up to 17 days the prospective buyers stayed, camping out in their vehicles overnight so they didn't lose their place.

Properties on the estate were on the market for between £4,500 and £7,000 in 1972

Peter Cole, then the Stowmarket reporter for the East Anglian Daily Times, remembers "the extremely long" lines of hopeful homeowners.

He recalls how a van drove along the queue to provide food and drink, while police officers were on hand to keep things under control.

"I was there every day for a fortnight, interviewing [people in] the queues. It was quite unusual. In those days, the A45, which is now the A14, came right through the middle of Stowmarket.

"There was an awful lot of traffic through the main street and then you had this side road with all these cars parked [in the queue]."

The buyers put down a £50 deposit to secure their home

Estate agents at the time said there was a shortage of houses nationally due to the post-war baby boom, while locally there was a lack of affordable properties for those willing to commute from Suffolk to London.

Properties on the Lockington Crescent estate were on the market for between £4,500 and £7,000 - considerably cheaper than in London, where homes were up to 30% more expensive, according to economic historian Prof Christian Hilber. It made queuing during the housing "rat race" a necessity, according to a report in the Stowmarket Chronicle.

"I think it's ridiculous but it's the only thing we really can do," one woman told BBC Radio 4's Today programme at the time.

"It's well within our price range and looking anywhere near London or even on the outskirts is just way above our pocket."

Sue Petty says camping out was "worth it in the long run"

Mrs Petty, originally from Enfield, travelled up with her then-fiancee Malcolm to secure a property. She says it was cold sleeping in their car and "there was not a lot of places to use the toilet" but they had "great fun and mucked in" with others in the queue.

Their patience was rewarded and they eventually bought their home for £4,750.

"That was a lot of money in those days," says the mother of two, whose husband passed away 17 years ago.

"We took a chance and this is the one we bought and I'm still here. I wouldn't move anywhere else."

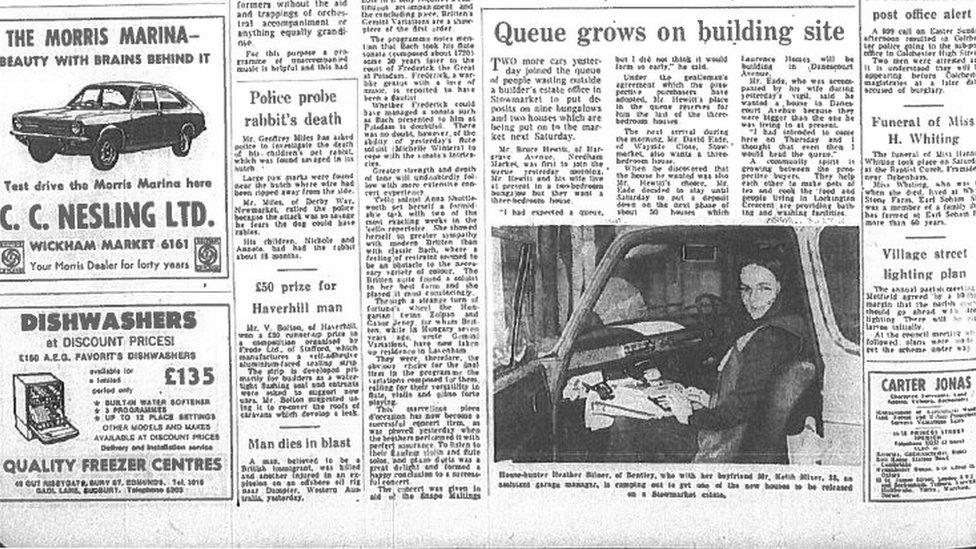

Heather Bilner, pictured in the East Anglian Daily Times, got engaged in the queue

As people bedded down in their cars, life adapted around them. A milkman delivered pint bottles to their doors and neighbours tapped on their windows with cups of tea at 07:00.

A letter was delivered to "David and Barbara, c/o the Queue of Cars in Lockington Crescent", while one couple - Keith Mixer and Heather Bilner - even got engaged while they waited, although they had to wait to get a ring because they couldn't leave the queue.

Many were rewarded for their determination and to make their success taste all the sweeter, the developers gave away 25 bottles of champagne - one to all those who had queued for more than 24 hours.

A "community" formed among the buyers who queued for their houses

Brian and Janet Horrex were lucky - they had already bought their £4,000 property on the estate as it had been built ahead of others and had watched as people waited patiently in their cars.

"It was rather extraordinary seeing people queue up, they were desperate to get here," says Mr Horrex, now 78. He added he and his wife Janet have had "no inclination to go anywhere else".

Rosie Bridges, who had grown up on nearby Lockington Road, remembers being shocked when the developers moved on to the farmland where she and her friends used to play.

"When they said they were going to knock through and build an estate, it horrified us. They brought coach-loads from London to see the houses and the showroom."

You might also be interested in:

The 66-year-old moved away from the area when she married her husband Colin, but the couple returned some years later and bought the final house on the estate to be built.

"It was going to be just the houses either side but they decided they could slip another house in there," she says.

"They didn't even have enough bricks to finish it - this house [was never supposed to] have been built."

Fellow long-time resident Ernest Eames remembers more houses being built to meet demand.

"Gazumping, external was very rife at the time," says the 75-year-old. "Thirty extra properties were included because everything was selling so well, they managed to squeeze in 30 extra buildings."

Mr and Mrs Horrex's home was built ahead of others on the estate

The Horrexes say they have "no inclination to go anywhere else"

It is hard to imagine that anyone would go to such lengths for a property now.

"I can't see people doing it like that these days, it's all on the internet, people just bid online these days," says Mrs Petty.

And yet, it has happened as recently as May. People desperate to buy in the Gleeson Homes development in Rochdale parked for days, external while relatives brought them food, sleeping bags and hot water bottles.

In June 2018, queues formed outside an estate agents in Belfast , externalas prospective buyers waited to snap up a "luxury" property on the city's development off Ballygowan Road, while more than 400 people queued at the doors of Galliard Homes, external to get their hands on a west London apartment in September 2017.

Rosie and Colin Bridges' home was the last to be built on Lockington Crescent

But Prof Hilber, from the London School of Economics, says the housing climate now is very different to the "sellers' market" of the 1970s, which was characterised by rapid economic growth fuelled by a "deregulation of the mortgage market and large tax cuts".

Now, he says, it is driven by a "dysfunctional planning system".

"As cities have grown the constraints have become very binding. Cities in England can't grow horizontally (green belts), vertically (height restrictions and view corridors) and can't easily renew... due to preservation policies.

"There is not enough new supply to catch up with demand growth. If a suitable dwelling comes on the market that is semi-affordable for younger households, we will still observe queues, even during downturn periods."

To hear more about camping out for a property, listen to the BBC Multi Story podcast Dwelling.

Get in touch

We'd love to hear your stories from around England and you can use the tool below to contact us. Or if there's anything you'd like us to investigate or a question you'd like us to answer, submit your details and we could be in touch.

If you are reading this page on the BBC News app, you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question on this topic.

- Published15 May 2019

- Published30 March 2019

- Published9 July 2020

- Published4 April 2018