The long-misdiagnosed student heading to Cambridge to study medicine

- Published

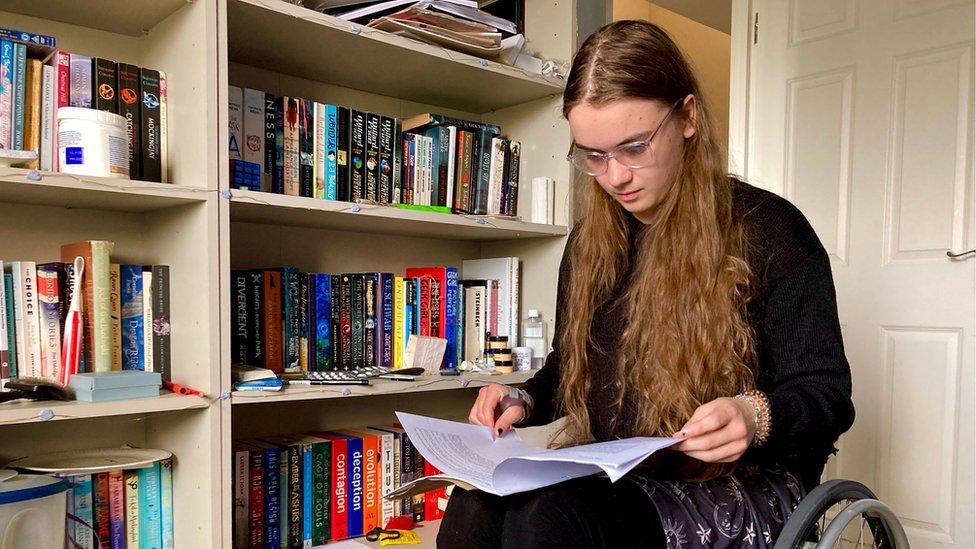

After a spell in hospital, Katy, 18, began her A-levels at Thurston College, near Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk, two months late and using a wheelchair

For years, Suffolk teenager Katy Shaw's symptoms were either misdiagnosed or not believed. Eventually she was found to have a genetic disorder that caused constant dizziness, fainting and pain when standing. After a spell in hospital, she began her A-levels two months late and using a wheelchair. Here she shares her story and explains what heading to Cambridge to study medicine means to her.

The main condition I have is Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, external (EDS), a genetic connective tissue disorder I was born with.

Connective tissue is found throughout the body and is responsible for holding organs, tissues, ligaments and other structures together correctly, so having EDS means my connective tissue is too loose and fragile - causing issues with my joints, skin and other internal organs like my bladder.

I have had issues all my life, including frequent bladder infections, bruising, migraine episodes and joint pain.

However I wasn't diagnosed with EDS until the age of 16 as I only developed more severe symptoms as a teenager, and EDS is generally not well understood by many of the doctors I have met.

When I was about 14 years old, I began noticing that I felt dizzy and light-headed when I had to stand for more that a few minutes and would need to sit down a lot.

This was the beginning of a condition called Postural Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS), a common comorbidity of EDS.

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

Jameela Jamil is one of the most high profile celebrities who lives with the disease

Descriptions can be found from the 1680s and 1890s, but the first canonical accounts came from Edvard Ehlers, a Danish dermatologist, in 1901, and the French dermatologist Henri-Alexandre Danlos in 1908.

In 1936, the name "Ehlers-Danlos syndrome" was proposed and three cardinal symptoms were identified: joints had to be overly bendy, and skin had to be both stretchy and unusually "friable", meaning it crumbled easily.

However, this simple picture did not stay simple. Over the coming decades, physicians realised there was more than one type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Quite how many is still uncertain. In 1967, a surgeon claimed there were three subtypes, based on 27 cases with differing symptoms.

Two years later, another argued for five subtypes after carefully studying 100 people. By 1988, 11 subtypes had been found.

Source: BBC

With POTS many patients, myself included, have very high heart rates when standing or sitting up and this can lead to fainting very easily.

I also have issues with regulating my blood pressure and body temperature.

I began to have frequent fainting episodes, as well as constant dizziness and chest pain when standing.

At the worst of this, I was fainting upwards of three times a day and was forced to quit competitive swimming, a sport I had enjoyed for years.

Due to being unable to be as active as I wanted, I lost a lot of muscle which caused my joints to deteriorate and dislocate frequently.

Katy, who lives in Stowmarket, got top grades in her chemistry, physics, biology and maths A-levels

I was in immense pain and feeling ill every day, but I continued attending school as I needed to have a routine to focus on, and I struggled to acknowledge how unwell I was becoming and accept help from others.

My difficulty coming to terms with my illness is partly due to me being autistic and struggling to interact with people while under that amount of stress, but it was also due to the dismissive attitude of the paediatric doctors I was under at the time.

I was told my fainting and high heart rates were due to anxiety and that it was up to me to manage my stress in order to get better.

I was referred to a psychologist "to help me cope with my illness", who told me that all my issues, including my shoulder which had been partially dislocated for days, were due to stress, and I needed to practice mindfulness and cognitive behavioural therapy to get better.

In reality, I was already doing everything I could, and hearing this made me feel like this was all my fault and made it that bit harder to address the mental and physical toll this was taking on me.

Once Covid hit in March 2020, I was only getting worse.

I was unable to stand for more than a few seconds and spent most of the first lockdown in bed.

You might also be interested in:

The few attempts I made to get out of the house were met with trips to the emergency department after passing out and hitting my head in public.

Eventually, I was referred to a rheumatologist under adult services who diagnosed me with EDS after one appointment.

At the time, I wasn't even scared of the implications of a lifelong illness, I was just relieved to hear this wasn't all in my head.

However, a diagnosis didn't change much for my health. On 27 August 2020, I began to lose movement in my legs while doing my physiotherapy exercises.

By the next morning I had lost much of the movement in my arms and legs and was taken to accident and emergency by ambulance.

I spent seven weeks in hospital with a new diagnosis of a functional neurological disorder- in essence the extreme stress my brain and body had been under meant my brain was unable to send signals to my limbs correctly.

I was eventually discharged from hospital as a full-time wheelchair user, having missed the first two months of Year 12.

Katy taught herself A -level biology in just one year and received an A* grade for it

The first two weeks I was terrified because I didn't know how to fit in at sixth form or about being in a wheelchair at school.

I did notice from my classmates and from my peers that I got a lot of staring - I accept staring, I know I look different, especially if I was walking the last time these people saw me, and I had so many chats with people where they said they hoped I would get better soon and I had the knowledge that I was not going to get better soon or completely.

I just wanted to figure out how to do school now that things were different and to get on with it.

I have had people come up to me on the street - a stranger out of the blue - and ask me why I am in a wheelchair and they go 'oh, it's not permanent is it?' and I go, 'erm, yes it is permanent' and then they'll say they are sorry for me. This happens on a fairly frequent basis when I'm in public.

People do say they feel sorry for me or hope I get better soon and it is completely unnecessary - they don't need to feel sorry for me because for me the wheelchair is a good thing.

It means I can get out of the house, I can move around safely rather than passing out and hitting my head, which happened a lot. It means I don't get as tired because, when I was walking, I would get exhausted and was in so much pain by the end of the day that I couldn't do anything the next day.

The wheelchair means I can do things like study medicine.

As far as other people are concerned, I'm just a person sat in a wheelchair, you don't need to treat me differently just because I am in a wheelchair.

Seeing the wheelchair as a failure or as a last resort or as the worst case scenario is something that needs to change as well.

It is not a worst case scenario for me.

The worst case scenario would be not being able to do the things I enjoy.

Katy is about to begin studying medicine at the University of Cambridge after taking her place at Selwyn College

It has definitely been a difficult couple of years, I would be lying if I said it wasn't.

I've had a lot of challenges with my health and a lot of internal challenges dealing with the mental and emotional repercussions.

There are a lot of issues in medicine of patients not being listened to, not necessarily being believed.

A lot of that is down to doctors being overworked and the state of the NHS at the minute but when you present to a doctor with various symptoms to diagnose, they often get dismissed or put down to anxiety.

Looking at the idea of medicine as a profession and the goals that medics have and the duty of treating their patients, is something I hope to be able to make a difference with.

Part of being a professional is to be aware of what needs to change and be aware of how you're treating patients and populations a whole.

It gives me a motivation to help people in a different way, I think.

The experiences I have had and the sort of patients I want to help are the ones who go to appointments with these debilitating symptoms that go undiagnosed and unsupported for years. I was that patient before I actually got the right diagnosis and medication. There is still a long way to go.

Those are the patients I want to help - the ones who are not being believed or supported as much as they should.

As told to Laurence Cawley and Ian Barmer

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external. If you have a story suggestion email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published18 March 2022

- Published18 December 2021

- Published18 May 2021