Why did Norfolk and Suffolk flood after such a dry year?

- Published

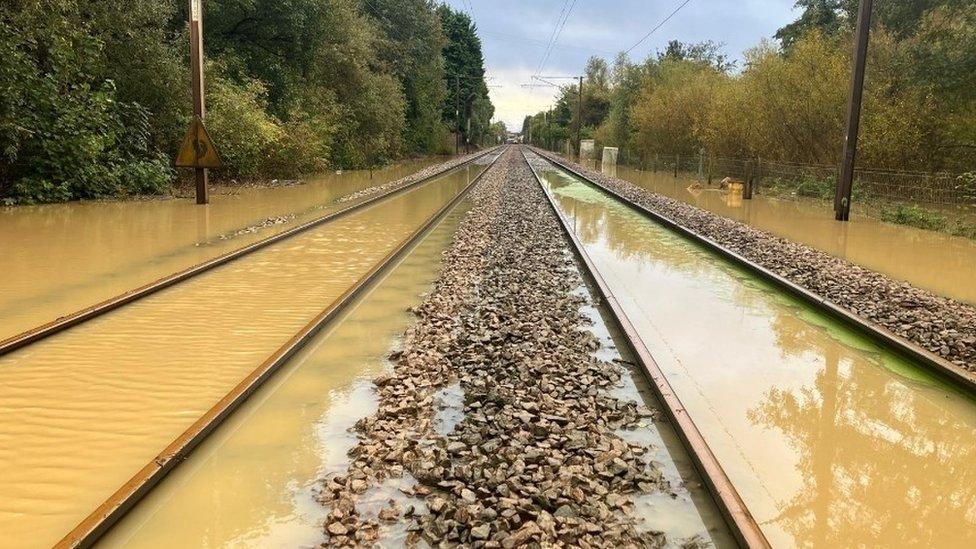

Large areas of Suffolk were severely flooded

Just a few weeks ago most of East Anglia was recovering from drought while September ushered in a heatwave. Why then did vast swathes of the area end up so badly flooded that families had to take refuge in leisure centres?

Local authorities in Norfolk and Suffolk believe hundreds of properties were flooded during Storm Babet.

Suffolk was so badly affected that a major incident - meaning the flooding posed a risk of serious harm, damage, disruption or threat to life - was in place for more than 24 hours.

Communities were seen pulling together as neighbours helped rescue each other amid the rising flood water.

In Framlingham, one of the worst-hit towns in which about 70 homes were affected, a herd of 17 cows was saved from drowning by members of the public, while in Wickham Market farmers used tractors to get through flood water and rescue people trapped in their homes.

How much rain fell?

As of last Thursday, Suffolk's total rainfall during October 2023 was 117.9mm (4.5in) which was 90% more than the average expected rainfall for the month

The Met Office's analysis of Storm Babet revealed that between 75mm (3in) and 100mm (4in) of rain fell across East Anglia during the four day storm.

As of last Thursday, Suffolk's total rainfall during October 2023 was 117.9mm (4.5in) which, a Met Office spokesman said, was 90% more than the average expected rainfall for the month.

Norfolk meanwhile has already had 77% more rain than expected for the whole of October, with 120.4mm (4.7in).

At a more granular level some records were broken, external.

Wattisham in Suffolk recorded its wettest October on record, BBC Look East weather presenter Dan Holley said, with 196mm of rain.

That is more than three times its average for the month, beating the previous record of 138mm set in 1960 (with data back to 1959).

What type of flooding was this?

Simon O'Brien pulling people to safety in Debenham in his homemade paddleboat

Ask Prof Kevin Hiscock about flooding and he will tell you there are six types: surface water, pluvial, fluvial, groundwater, storm surges and tsunamis.

"The flooding seen in East Anglia was fluvial which is when rivers break their banks," said Prof Hiscock, professor of environmental sciences at the University of East Anglia.

"Rivers breaking their banks is a natural phenomenon," he said.

If people did not live on or near flood plains, the risk would be minimal.

Prof Hannah Cloke, professor of hydrology from the University of Reading, says "lots of exposed landscapes" also made flooding worse in places.

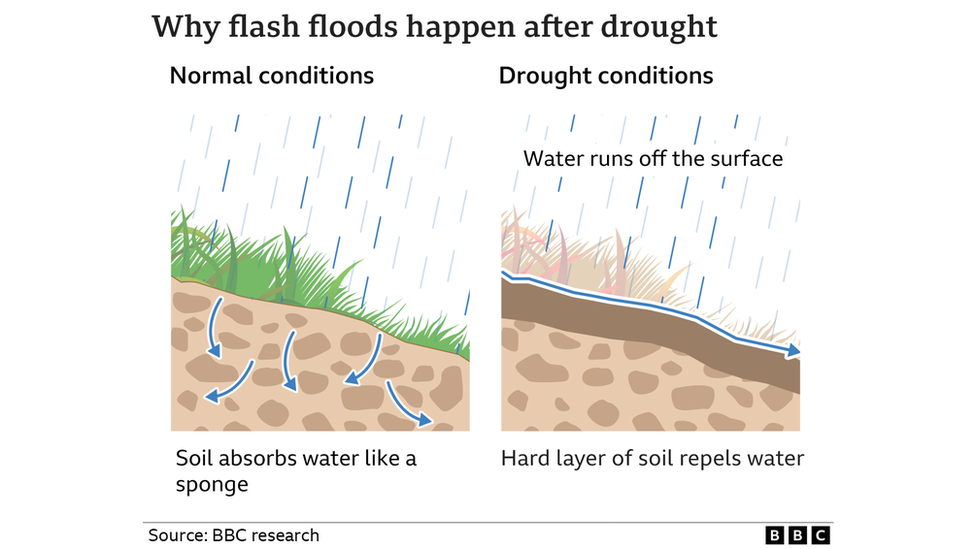

"We did see rivers burst their banks, but also where we had compacted soil in big agricultural areas, that water rushes straight off," she says.

Did the drains do their job?

An aerial view shows how bad the flooding was in Framlingham

"In our older towns and cities, the sewerage and drainage systems were not designed for the amount of housing we now have, which means they can get overloaded," says Prof Hiscock.

"It is why in heavy rains you sometimes see manhole covers popping up with water coming out."

Prof Cloke says: "You're really looking towards major changes to the way we build and where we choose to live."

She believes it is not just about preventing flooding but also storing water to avoid future droughts.

"We need to think much more imaginatively about what we do with water when it does fall, so that we can hold on to it when it's drier in the summer," she says.

Why were some areas worse hit than others?

Prof Hiscock suggests storm cells mean more rain is released over some places than in others

Asked why some places, such as the village of Debenham, were particularly badly hit, Prof Hiscock suggests storm cells play a role.

Far from being a monolithic mass carrying the same amount of rain across every square inch, he said, some parts of a storm can carry very different amounts of rain water.

"It means more rain is released over some places than in others," he said.

Dr Alexander Antonarakis, reader in global change ecology at Sussex University, says places without tree cover are particularly vulnerable.

"We have cut our forests and natural landscapes, but forests are crucial in sucking up rainwater and maintaining soil structure," he says.

"Forests on floodplains are also key in helping to block the flow of water once a flood does happen."

Does soil type make a difference?

Yes, says Prof Hiscock.

"In the very northern part of East Anglia the soil is more silty and sandy," he said. "It is called 'lighter land' in agricultural circles.

"To the south is the heavy land which is clay rich and not as permeable, which means a greater risk of surface flooding.

"They are both glacial in origin but respond to rain differently."

Earlier this month, the Environment Agency said: "At the end of September, most of the area was in recovering status for drought."

However, the agency said that unlike 2022, 2023 had not been a particularly dry year.

"Autumn in particular is proving to be wetter than average for large parts of East Anglia. Some parts of East Anglia received a month and a half's worth of rain in 48 hours."

How did the recent flooding compare?

"Storm Babet in East Anglia was a roughly once in every 16 year event," says Prof Hiscock.

"It is not unusual to see flooding in later winter when the soil is already recharged with water.

"It is a bit unusual to see it so early in the autumn.

"That said it is not the first time we have had an event like this - it is the fourth largest one since 1959. It was dramatic to see and, of course, we've built more houses since 1959."

What role did climate change play?

Professor of Hydrology Hannah Cloke says the UK "urgently" needs to adapt its infrastructure and public awareness in the face of storms like Babet

While Prof Cloke acknowledges that "it is a bit too early to exactly pinpoint what happened", she says storms like Babet are "getting worse because of climate change".

"We know that we have more energy and heat in the oceans and the atmosphere, and that means we can pick up more moisture from the sea, and the air can hold more rain.

"That means heavier rainfall totals for these types of floods."

Prof Cloke says that while appropriate development and infrastructure is needed to cope with future flooding, another urgent need is public awareness.

"We need to make sure everybody is aware they might be at risk, so people know what to do in an emergency and they don't try to drive through floodwater or put themselves at risk."

"It's really important to make everybody aware that this is a problem. And it's going to get worse."

Follow East of England news on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external. Got a story? Email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external or WhatsApp us on 0800 169 1830

Related topics

- Published27 October 2023

- Published24 October 2023

- Published24 October 2023

- Published22 October 2023

- Published21 August 2023

- Published1 March 2023

- Published15 August 2022