Calls to 'end secrecy' over Guildford IRA pub bombings

- Published

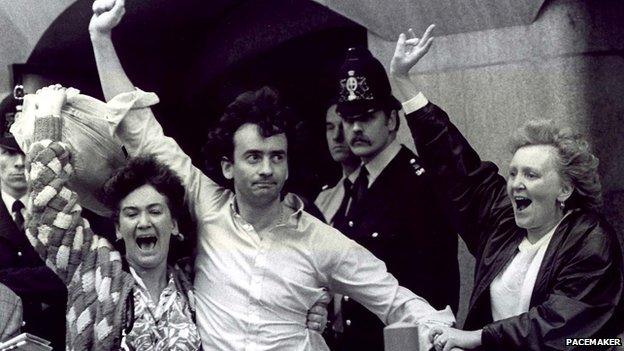

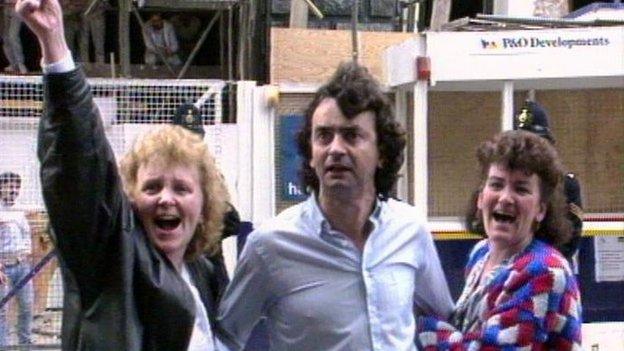

The Guildford Four were released in 1989 amid doubts about police evidence

It was a case that shattered confidence in the British legal system, sparked an Oscar-winning film and eventually an apology from a prime minister.

Some thought when Tony Blair apologised to Gerry Conlon, Paddy Armstrong, Paul Hill and Carole Richardson, it drew a line under one of the most scarring episodes of the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

But supporters of the group, known as the Guildford Four, believe the fight for justice continues.

Campaigners have fought to see secret documents relating to the case and now a lawyer has claimed a 30-year embargo on their release has "magically" been changed to 75 years.

The BBC has submitted a request to see the papers and sought clarification on the embargo from the British government, but despite repeated requests has not received a response.

Police on trial

The Guildford Four were jailed for life after the IRA detonated bombs at two pubs in Guildford, external on 5 October 1974, killing five and injuring scores more.

But, the four always protested their innocence and in 1989 the Court of Appeal quashed their sentences, amid doubts raised about the police evidence against them.

The case became considered one of the worst miscarriages of justices in British legal history.

Forty years on from the bombings, and 25 years after the Guildford Four were freed, fresh calls for the results of a public inquiry into the scandal to be published in full have come from solicitor Alastair Logan, who represented the group.

He wants evidence received in private during Sir John May's inquiry - held from 1989 to 1994 - to be made public.

Mr Logan, who sits on The Law Society's Human Rights Committee, external, said part of the inquiry was held in secret because three Surrey Police officers - who were later cleared - were facing trial on charges of conspiracy to pervert the course of justice.

"The consequence of that was neither the defendants nor their legal representatives were entitled to be present or to know what evidence May had given to him," he said.

He asked to see the evidence at the time of the inquiry but was told it was embargoed for 30 years.

But this year, it emerged in news reports on Gerry Conlon's death the embargo had changed to 75 years, he said.

'Conlon's dying wish'

"We have no explanation, firstly as to why it [the embargo] was changed, or any explanation as to why they should have been embargoed anyway. After all, it was a public inquiry," he said.

When asked what he believed was in the papers, Mr Logan said: "I suspect, lies."

Guildford's night-life was popular with the thousands of military personnel in the area

Two bombs went off in the town that night - the IRA's "Balcombe Street Gang" later claimed responsibility

He said he believed police officers and others involved in the case knew the report would be secret and they could not be challenged and "could have continued lying".

Mr Logan said: "I suspect that that's the probable reason why 75 years has been substituted for 30 - just to make sure that everybody in any connection with the case is long dead before the papers ever come out."

He said the damage done to the Guildford Four and their families had been enormous - with what he described as conspiracies to keep young, innocent people in jail for 15 years.

"I don't feel that justice is seen to be done if there are secret deals going on, secret parts of Sir John May's inquiry [and] secret documents held by the government," he said.

Mr Logan sought clarification from The National Archives, which holds the papers at Kew, but has not yet received an answer.

But a spokeswoman for The National Archives told the BBC the closed records for the inquiry had a "review date" of 2019, which had not changed. But, she did not make clear whether that meant the papers could be made public at that point.

'Police culture not violent'

Mr Conlon demanded the release of the papers before he died, the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) revealed this year.

The SDLP, which draws most of its support from the nationalist community, told David Cameron at prime minister's questions that Mr Conlon and accompanying people had been promised access to the archives and asked for the "dying wish of an innocent man" to be honoured.

The Northern Ireland Office, when asked whether any action would be taken, told the BBC it was seeking more information from the SDLP about what had been said to Mr Conlon - but the SDLP said it was waiting to hear from the government.

When the BBC contacted the government to seek confirmation of the embargo and an explanation about why the papers were kept secret, it was passed from the Northern Ireland Office, to the Home Office, and then to the Cabinet Office, and then back to the Home Office.

Calls to place the papers in the public domain have also come from former police officer Robert Bartlett, who was on duty on the night of the bomb attacks.

Mr Bartlett remembers arriving at the scene to find a dead body in a gutter, injured people sitting lined up against a wall, and dozens of hysterical, angry, upset people.

As the first officer entered the Horse and Groom pub, the floor gave way and the injured, dying and dead fell into the pub cellar, he said.

A second bomb exploded half an hour later in the nearby Seven Stars pub. But, as a result of evacuations following the first blast, there were few further casualties.

He said police dealt with the aftermath professionally, but as accusations against the force emerged over the years he was left with no idea what had happened.

'Policing improved'

Calling for the release of Sir John May's findings, Mr Bartlett said: "I would like to see all the background, because what I know at the moment is the police officers that were prosecuted were found not guilty and that the alleged offence they committed was marginal."

He also said he had never believed the Guildford Four were subjected to violence by officers. Gerry Conlon had always claimed he was stripped, beaten and tortured.

Mr Bartlett said: "It was not the culture."

After the Guildford Four were released, an investigation into the case by Avon and Somerset Police found serious flaws in the way the Surrey force handled the case.

In a statement, Surrey Police said discrepancies in police records were discovered during the Avon and Somerset inquiry, and when the convictions were quashed the force accepted that decision.

It said the conduct of individuals in relation to their recording of interview notes and evidence given at trial became the subject of exhaustive enquiries, which led to three officers standing trial and being acquitted in 1993.

The statement said: "Surrey Police has never sought to underestimate the importance of this aspect of the case which was dealt with in detail by the May inquiry report."

"[But] policing has evolved significantly in the past 40 years and it is difficult to make comparisons to how the investigation was undertaken in 1974 when compared with today.

"Custody and prisoner processes have greatly improved and are closely regulated and there is a dedicated counter-terrorism policing structure in place nationally."

The perpetrators of the attacks were never prosecuted.

The "Balcombe Street Gang", a four-man IRA unit, later claimed responsibility, external but were not charged.

They had been given life sentences after a bombing campaign in the 1970s, but were released, external under the Good Friday Agreement.

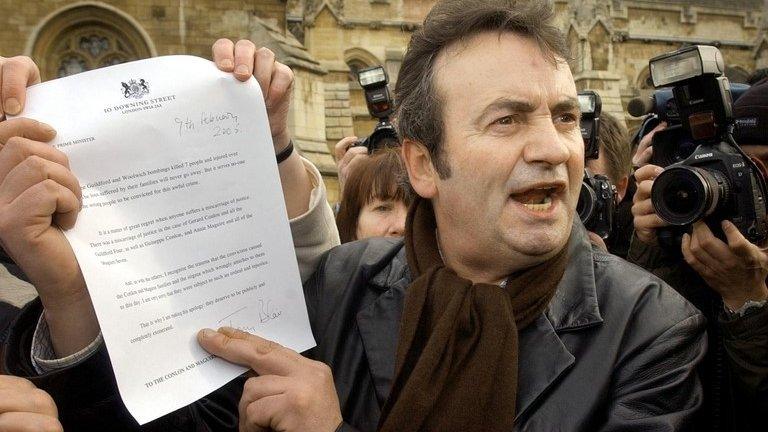

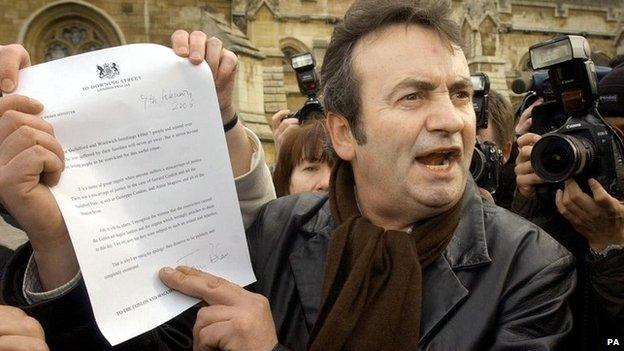

Gerry Conlon received an apology from then Prime Minister Tony Blair in 2005

Prof Marie Breen-Smyth, external, from the University of Surrey, has called for a full, open inquiry.

She said people needed "the clear light of day shone on all of the dark corners".

The Guildford attacks were among the IRA's first attacks on the mainland, and she said the organisation's political motives were to give people in the Home Counties a taste of what life was like in Northern Ireland, and to increase pressure on the British Government.

Guildford was known as a "garrison town", with several barracks nearby, at Stoughton and Pirbright and Aldershot in Hampshire, and a night-life that was popular with the 6,000 military personnel, external then in the area.

Prof Breen-Smyth, a politics expert from Belfast, said there had been two wrongs - the pub bombings themselves and the miscarriage of justice.

She said: "We know who did the bombings.

"We don't know who did the miscarriage of justice, because the miscarriage of justice was perpetrated by people within the justice system."

'Shameful episode'

And she said: "I would welcome the opportunity for the files to be put into the public domain so we can actually see what went on. That's not happened.

"Apologies are fine and well and they're certainly help, but they do not reinstate justice.

"They do not give people back lost decades of their lives."

Prof Breen-Smyth said after the attacks and subsequent arrests, no Irish person visiting the mainland felt entirely safe, and another of the casualties of the bombings was justice.

"It really needs to be seen by those who are watching and regarding it as a shameful episode that people have left no stone unturned to reinstate the good name of the British justice system," she said.

Twenty five years after the Guildford Four were released, there remain calls for a full inquiry

- Published28 June 2014

- Published23 June 2014