Cleveland child abuse crisis doctor calls for new inquiry

- Published

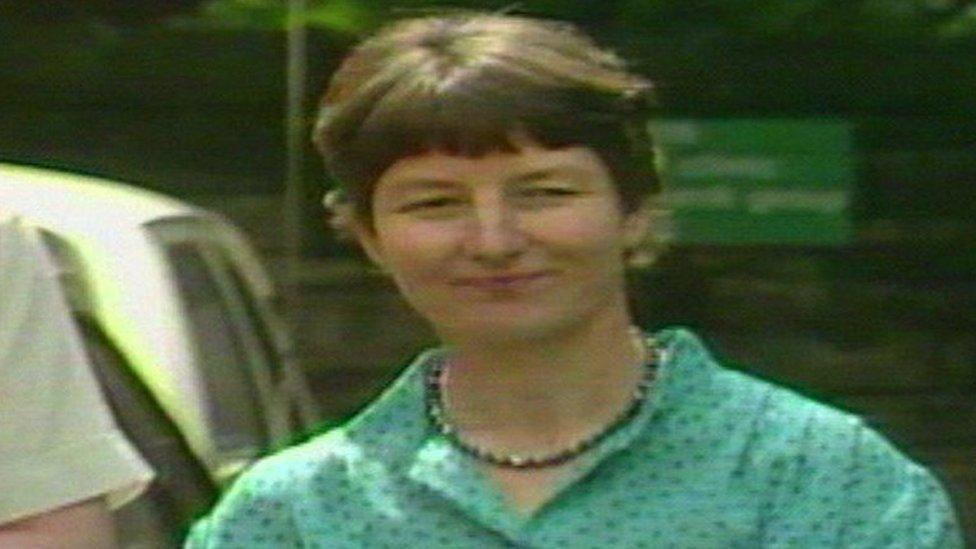

Dr Geoffrey Wyatt said he was wrongly vilified for diagnosing sexual abuse in children in 1987

One of two paediatricians at the centre of the 1987 Cleveland child abuse scandal has called for a new inquiry, 35 years after the first investigation.

In 1987, more than 120 children were taken from parents after two doctors said they had found signs of abuse, but most were returned to their families.

A judicial inquiry the following year heavily criticised the doctors, Geoffrey Wyatt and Marietta Higgs.

But Dr Wyatt says new evidence suggests his original assumptions were correct.

It follows the publication of a new book, Secrets and Silence, by the journalist and campaigner Beatrix Campbell.

Dr Marietta Higgs was also criticised by the 1988 inquiry

In 1987, Dr Wyatt and Dr Higgs used a new, and controversial, intimate physical test which they said found signs of abuse in 121 children over a five-month period.

The children were removed from their parents, but 98 were later returned to their family homes after the doctors' diagnoses were deemed to be incorrect.

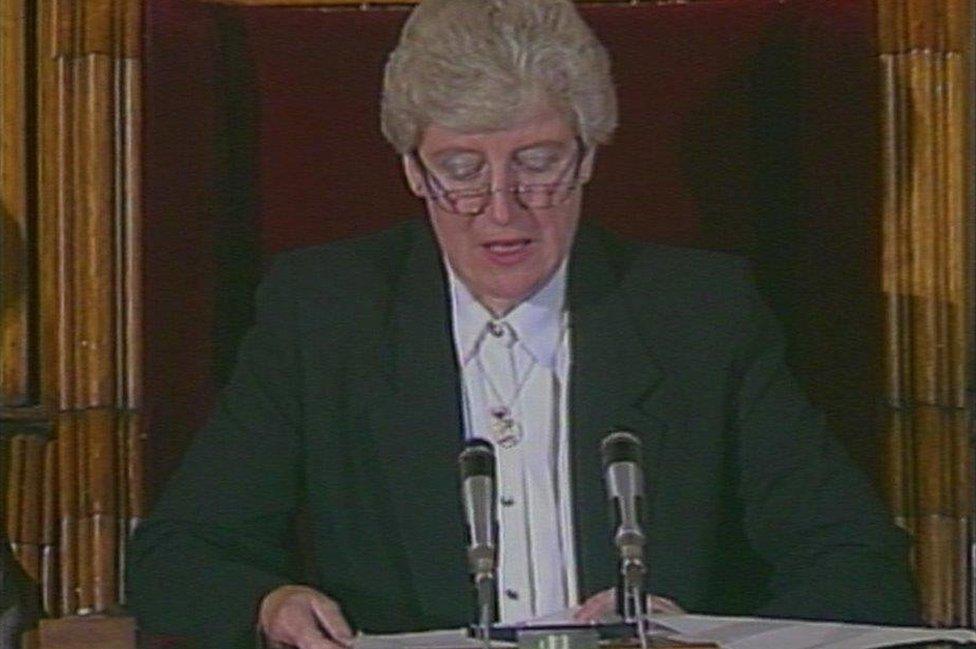

In a 1988 inquiry that followed the scandal, Lord Justice Elizabeth Butler-Sloss, as she was known then, said Dr Wyatt had "caused unnecessary distress to children" and "lacked common sense".

Her report also criticised Dr Higgs for "relying unduly on physical signs" and said she was "too fixed on her judgement that children should be separated from parents".

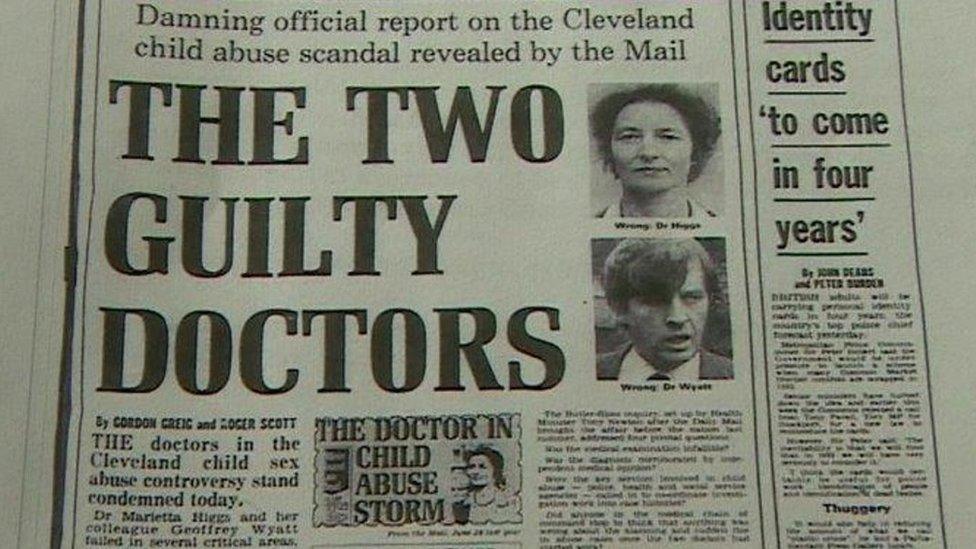

The two paediatricians were vilified in the media and both were disciplined by the regional health authority, with Dr Wyatt prevented from working on child abuse cases for the remaining 22 years of his career.

Both doctors were vilified in press coverage of the Cleveland scandal and the subsequent inquiry

But Dr Wyatt says the public may have been misled.

He said Ms Campbell's new book provided evidence from The National Archives that the government in 1988 had been advised that "at least 80%" of their diagnoses of sexual abuse were, in fact, correct.

A letter between government departments stated: "Comments in this area are liable to be turned back on us later as bids for extra expenditure."

Dr Wyatt told the BBC Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher knew an "independent assessment" carried out by the Department of Health showed the tests had a diagnostic accuracy of 80%.

"She didn't tell the House of Commons," Dr Wyatt said, adding: "I don't think you can have a clearer example of misleading Parliament than that."

Lord Justice Elizabeth Butler-Sloss carried out the inquiry in 1988

Dr Wyatt said he couldn't see how he "could or would have done anything different".

"I think what Dr Higgs and I were trying to do was address the issue of the possibility of sexual abuse in the absence of a clear statement from the child," he said.

He added "nothing has changed" and a new inquiry was needed, adding: "I want to try to protect children and the present situation is, frankly, appalling."

He said specialist assessment teams were needed, and doctors should be "protected to report concerns about suspected sexual abuse".

Dr Wyatt said he was wrongly criticised in 1987

A government spokesperson said it did not comment on the business of past administrations.

The spokesperson added: "We remain firmly committed to tackling child sexual abuse and working with agencies following the independent inquiry into child sexual abuse, to ensure children are never again so badly let down by the institutions that should have protected them.

"We are making good progress on our commitment to introduce a mandatory reporting duty and will continue to engage with a wide range of charities, victims and survivors to ensure we use all levers we can to tackle this horrific crime and keep children safe."

Follow BBC Tees on Facebook, external, X (formerly Twitter), , externaland Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to northeastandcumbria@bbc.co.uk, external.