Rudolf Abel: The Soviet spy who grew up in England

- Published

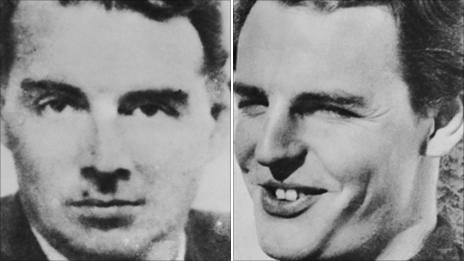

Rudolf Abel was arrested in Brooklyn after his cover was blown

The arrest and trial of the "most famous Soviet spy of all time", Rudolf Abel, is the inspiration for the latest Steven Spielberg blockbuster, Bridge of Spies. But who was Abel and what is the story behind his unlikely upbringing as a grammar school boy in the north-east of England?

"Red spy nabbed" screamed the Pathé News broadcast of October 1957 as Rudolf Abel was marched away in handcuffs.

It was the archetypal Cold War tale - an undercover operative arrested after his cover was blown.

Spared the electric chair, Abel was sentenced to three decades in prison. But just over four years later he would be handed over in return for Gary Powers, an American apprehended by the Soviets when his U-2 plane was shot down in 1960.

As an intelligence colonel, Abel was the highest-ranking Russian to face spy charges in the US. He had worked as a radio operator during World War Two before taking a role with the Foreign Intelligence Service as a translator and then joining a forerunner of the KGB.

But while Abel was what he called himself when taken into custody in the US, perhaps unsurprisingly for a secret services emissary, it was not his real name.

Mark Rylance, centre, plays Rudolf Abel in Bridge of Spies alongside Tom Hanks as his American lawyer, James Donovan

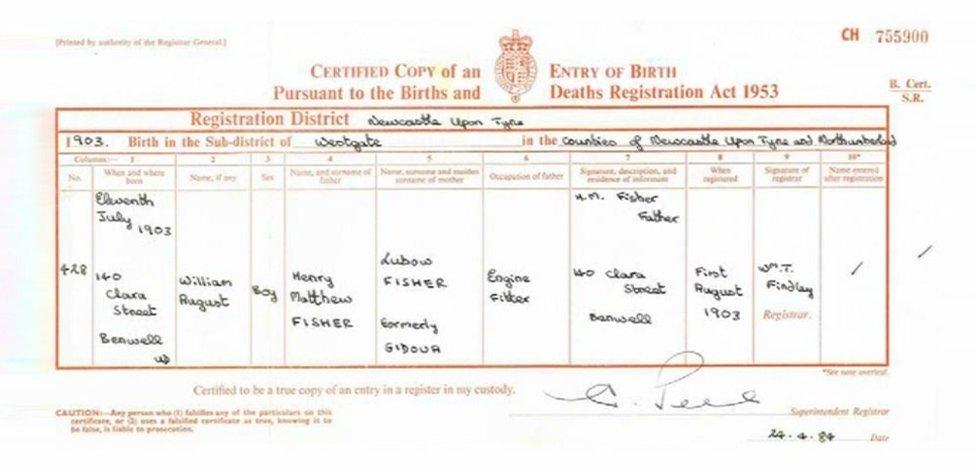

"He was born William Fisher on 11 July 1903 in Benwell, in Newcastle's West End," says David Saunders, a professor of Russian history at Newcastle University, who has been instrumental in uncovering the full story of the spy's childhood.

Spotting a review of a Russian language book by former spy Kirill Khenkin in The Times Literary Supplement in 1983, he was amazed to read of Abel's English childhood and set about obtaining a copy of his birth certificate.

"Abel was familiar to me," says the professor. "I remembered the exchange of 1962. He's the most famous Soviet spy of all time.

"We make a lot in this country about Kim Philby and the Cambridge Five, but those British spies didn't have any rank in the KGB. Abel is the only British-born ranking officer in Soviet external security services that we know of.

"He was born at 140 Clara Street, a property which is no longer there, and his family lived at a number of other addresses - Greenhow Place, Hampstead Road, Armstrong Road - from 1901."

William Fisher (top left) pictured in a family photograph as a schoolboy

Fisher's birth certificate shows he was born in Newcastle on 11 July 1903

In 1908, William's parents would move their two sons out of the city for the fresher air of the nearby coast.

"William sketched and was artistic. He was also musically talented. It was a middle-class life of a kind," says Prof Saunders, who describes a gifted youngster who - to the outside world at least - enjoyed an ordinary existence.

But the future spy's father was no ordinary man. A Bolshevik revolutionary, Heinrich Fisher was a "staunch socialist" and had been imprisoned in his home country by the Tsarist authorities.

He and his wife Lyubov emigrated from Russia in 1901, making their way across Germany.

Newsnight's Stephen Smith speaks to director Steven Spielberg

"He'd been a metal worker in St Petersburg and almost immediately got a job as an iron turner at Armstrong's [in Newcastle] and then as an engine fitter," said Prof Saunders.

"In 1921 he took the family back to Russia. It was now a Communist society."

William Fisher would never return to Tyneside.

Vin Arthey, author of Abel: The True Story of the Spy They Traded for Gary Powers, believes the years he spent in the North East would have helped shape his political views.

"The north-east of England at the beginning of the 20th Century was textbook territory for Marxism: heavy industry, the wealth concentrated in few hands, the working class living in pretty grim conditions.

"He was a committed Communist, as his parents were, and he joined the Red Army as a radio operator.

"A skilled linguist - a native English speaker, as well as Russian and German from his parents and French from Monkseaton Grammar School - he got a job as a translator."

Bridge of Spies focuses on Abel's arrest and lawyer Donovan's role in negotiating his exchange

Soviet security service postings to Oslo and London followed in the 1930s before World War Two saw him heavily involved in radio deception in efforts to trick German forces. It was, says Dr Arthey, the "most significant contribution" of his career.

The KGB colonel would arrive in the United States illegally in 1948. Working without diplomatic cover as a photo finisher, he assumed a number of identities as he "managed" agents.

"In 1948 Stalin was ailing, he died in 1953," says Dr Arthey. "The FBI was working hard to disrupt Soviet spy rings, but Fisher kept the show on the road.

"I don't think his job was seeking out military secrets, but he was an important cog in the wheel that got information back to Russia."

But he was betrayed by a member of his own network and arrested in Brooklyn in 1957. News reports said he had "high-powered radios capable of receiving signals from Moscow".

In 1962 Abel was traded for Gary Powers, whose plane had been shot down over the USSR

He never revealed his true identity and stood trial on espionage charges as Rudolf Abel.

The name was in fact that of a fellow KGB colonel and had been deliberately chosen, says Prof Saunders.

As well as concealing the spy's true identity, it also acted as a means of "testing" defector Alexander Orlov by seeing whether he would inform his new American allies that Abel was not who he said he was.

No such alert was forthcoming and, found guilty by a jury, "Rudolf Abel" was jailed for 30 years before becoming part of the famous exchange of prisoners on the Glienicke Bridge that linked West Berlin with Potsdam - the first of several such swaps between 1962 and 1986.

The Glienicke Bridge, seen here following the Abel-Powers exchange, became a familiar spot for spy swaps and has featured in many films and novels

What, though, of the way he spoke? If Abel was brought up on Tyneside would he not have had an identifiable Geordie accent?

Like many aspects of the spy's life, the matter is shrouded in mystery.

"I've met everybody who knew him as an English speaker," says Dr Arthey.

"They said he didn't speak anything like [a Geordie]. The best we've got is that he spoke with a kind of Scots-Irish accent, which he told people was down to being brought up by an aunt in Boston.

"It has been impossible to find the existence of any tapes from his FBI interrogation. That's not to say they don't exist - they could be classified, or be hidden or lost - but there's no audio record of him speaking English that I know of."

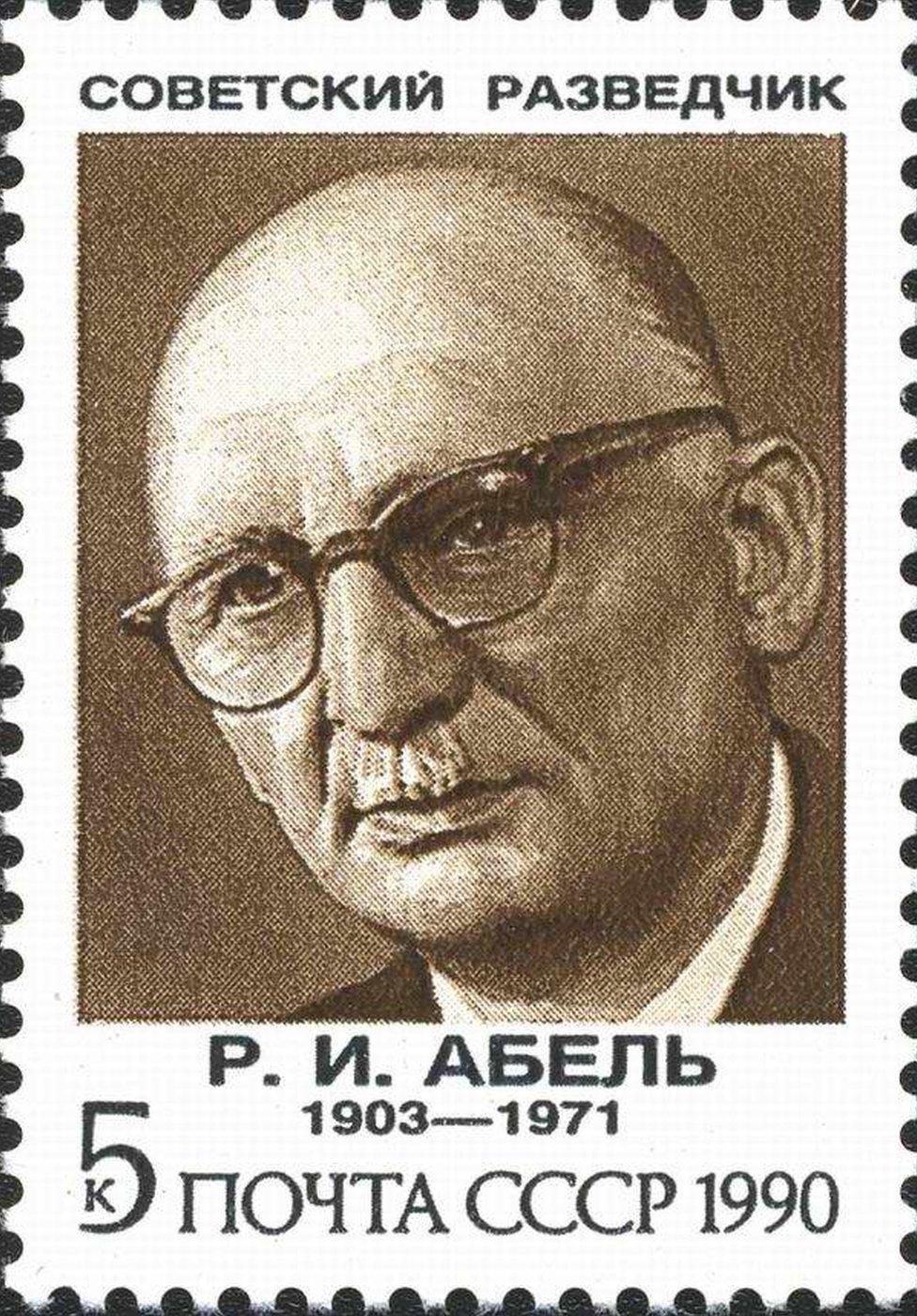

Abel died in Moscow in 1971, where his remains were interred at the city's Donskoy Monastery.

His tombstone bore his birth name of William Fisher - the identity that was never exposed during his captivity as one of the most notorious spies of the Cold War.

After his death, the spy's image adorned a Russian stamp

- Published15 October 2015

- Published30 June 2011

- Published8 July 2010