Our Friends in the North: What made it so special?

- Published

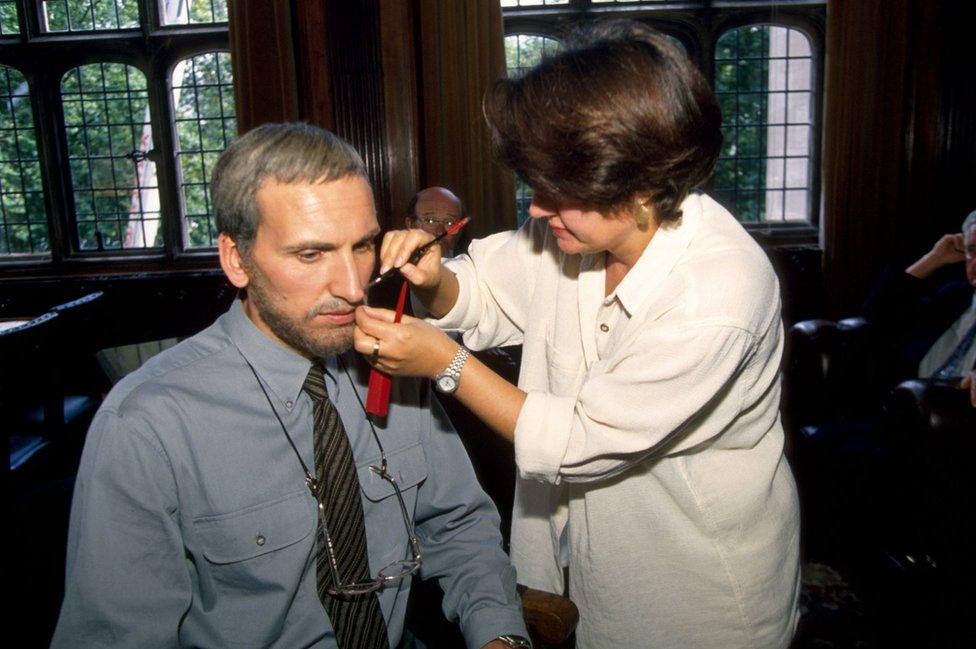

Christopher Eccleston, Gina McKee, Mark Strong and Daniel Craig took starring roles

Tracking the fortunes of four pals across the decades, Our Friends in the North was hailed a landmark drama. It is now 20 years since it first aired, but where does it rank among British TV's greatest hits?

Conceived as an epic tale of Shakespearean proportions, the sprawling series charting the highs and lows of Nicky, Geordie, Tosker and Mary transfixed millions of viewers in the mid 1990s.

Ambitiously marrying the personal and the political, the programme would follow the Tynesiders from their heady teenage days to a middle age scarred by shattered dreams.

But delayed by BBC reshuffles, legal worries and even the emergence of EastEnders, the programme's journey to the small screen was as tangled as the friendships it followed.

With the weighty subjects of town hall sleaze, police corruption and slum housing as its backdrop, the nine-part series made household names of Christopher Eccleston, Daniel Craig, Gina McKee and Mark Strong.

"It chimed with my politics coming from a working class background," says Eccleston, who took on the role of idealistic Nicky - a student who drops out of university to lead the fight for change in his home city of Newcastle.

Quickly seduced by the promises of smooth-talking politician Austin Donohue, he would devote his efforts to a battle against the establishment and spend decades dealing with the fallout of the rifts it caused.

"I heard stories in my own family about my Uncle Bill being sacked in the 30s, crying in a doorway and being too ashamed to go home, so all that stuff about the Jarrow Marchers resonated with me," he says.

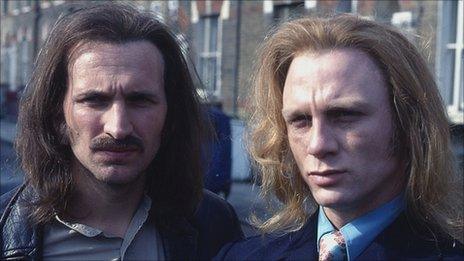

Craig's Geordie (left) and Eccleston's Nicky would encounter wildly different fortunes

"I knew it was epic, I knew we were doing something important. I felt it would have an impact because I knew my mam, dad and brothers would watch it and feel it very deeply.

"And if it was going to affect my family, it would affect families all over Britain."

Raised on the likes of the BBC's hard-hitting Play For Today, Eccleston, who was part-way through shooting the film Shallow Grave, was alerted to the project by the film's director, Danny Boyle.

"Danny said he'd read some scripts called Our Friends in the North, which was a 'state of the nation' piece. I promptly went to a phone box - there were no mobiles - and rang my agent.

"The key scene for me as I read the script was Peter Vaughan's character, Felix, being savaged by one of those pitbull dogs that everybody started buying in the 80s and 90s.

"Felix comes to the door and tries politely to deal with some feral member of the underclass who then sets his dog on him.

"It just shattered me because I knew what [writer] Peter Flannery was saying - this idealistic man who had pleaded the case for the working classes was being brutalised by the failure of the system."

While Eccleston had appeared in ITV crime drama Cracker and the British-made film Let Him Have It, McKee, Strong and Craig were still awaiting their big break.

All that would change when Our Friends in the North was broadcast from January to March 1996.

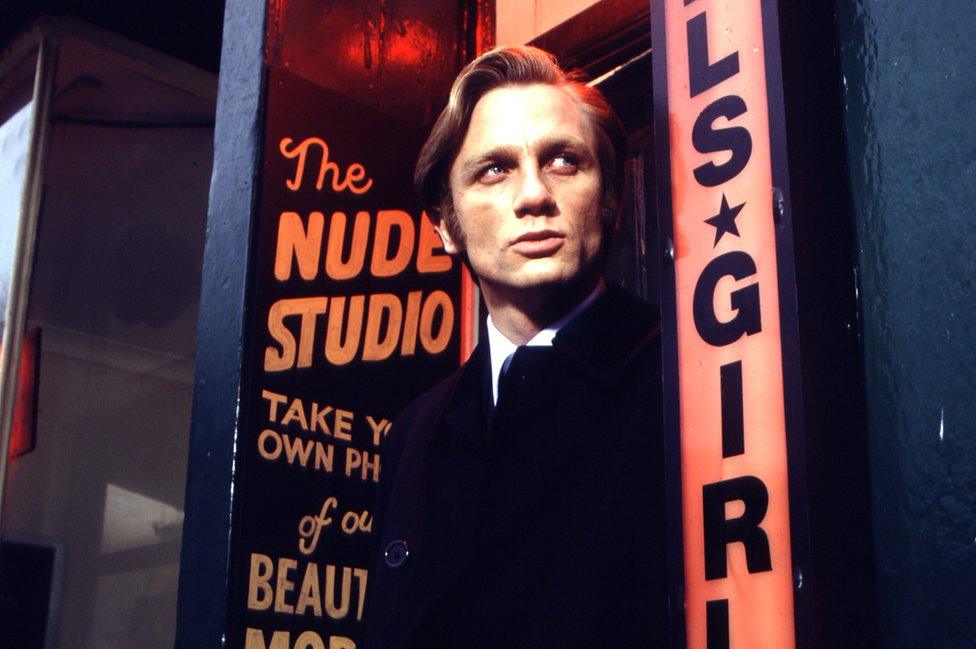

Geordie Peacock was drawn into the seedy Soho underworld

"I had the highest profile, but how things have changed," Eccleston says with a laugh. "Mark and Daniel are major movie stars and Gina's one of the greatest stage actors of her generation so there's a nice lesson in humility for me there.

"It doesn't surprise me. Daniel had a kind of rock star sexual charisma, which was perfect for Geordie, and Mark's an extraordinary character actor. Gina kept us all honest with the truthfulness and delicacy of her performance."

While Mary and Tosker would soon rue a loveless marriage, Craig's Geordie Peacock would head for the bright lights of London to escape beatings from an alcoholic father.

The addition of the future James Bond, though, came "very late", recalls Flannery, who is taking part in a question and answer session about the programme at the Whitley Bay Film Festival, external on Friday.

"We had almost cast a Geordie actor then the tape of Danny with an awful North East accent arrived," he says.

"He was undeniably magnetic. We thought we'd have loads of work to do on the voice, but the screen lit up when he appeared."

Problems, however, were apparent from the outset of filming. Stuart Urban, one of the series' two directors, was asked to leave 10 weeks into shooting.

"I was devastated by it because it was bad," Jarrow-born Flannery admits. "We were wrong to appoint him, we were rowing all the time on the set.

"I was poisoning it."

Eccleston says he "had fallouts" with writer Peter Flannery, but is full of praise for his friend's "incredible story"

Scheduled to helm the final four episodes, Simon Cellan Jones was enlisted to play a bigger role and the opener was reshot by Pedr James - with Flannery taking the opportunity to heavily amend the script.

It was a move not without problems.

"There's an opening episode no-one has ever seen, although I've got a copy," Flannery says.

"One of the producers came up with the idea of writing a different story as long as it met up with episode two.

"The actors went mad. They said, 'How can you change our characters?' I think they were on episode five by that point."

That things did not run smoothly when the cameras finally began to roll was perhaps not surprising as the adaptation had spent more than a decade in development hell.

Flannery penned the story in 1981 while working as a writer-in-residence with the Royal Shakespeare Company.

"I thought don't write a two-hander. Write a big play they can put on - a chronicle of our times."

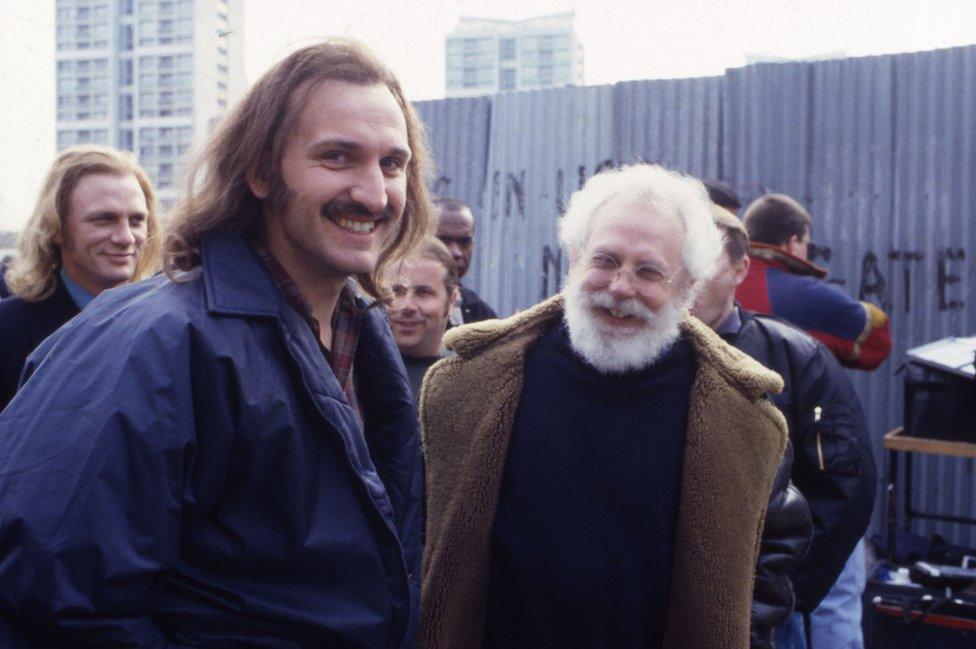

Mark Strong's Tosker married Gina McKee's Mary, but their union would flounder

Initially running from 1964 to 1979, the characters' journey concluded with Margaret Thatcher's rise to power, rather than the TV series which followed the characters up until 1995.

First performed in 1982, it came to the attention of the BBC. Flannery's hopes of a hit on the small screen would soon be dashed, though.

"By the time I was delivering it in about 1984/85, it was now a BBC One project and the channel had a new controller, Michael Grade," he says.

"He was looking for a soap set in London's East End and that's what he got."

There would be a further false start towards the end of the 1980s when BBC lawyers stepped in over concerns some of the characters were based too heavily on living real-life figures, such as disgraced Tyneside politician T Dan Smith.

Flannery would finally resurrect the project as a nine-parter, but almost scuppered its chances in a year-long row with the BBC over varying the length of each chapter.

"It was a monumental struggle - long and painful - but I have no real regrets," he says from his Oxfordshire home.

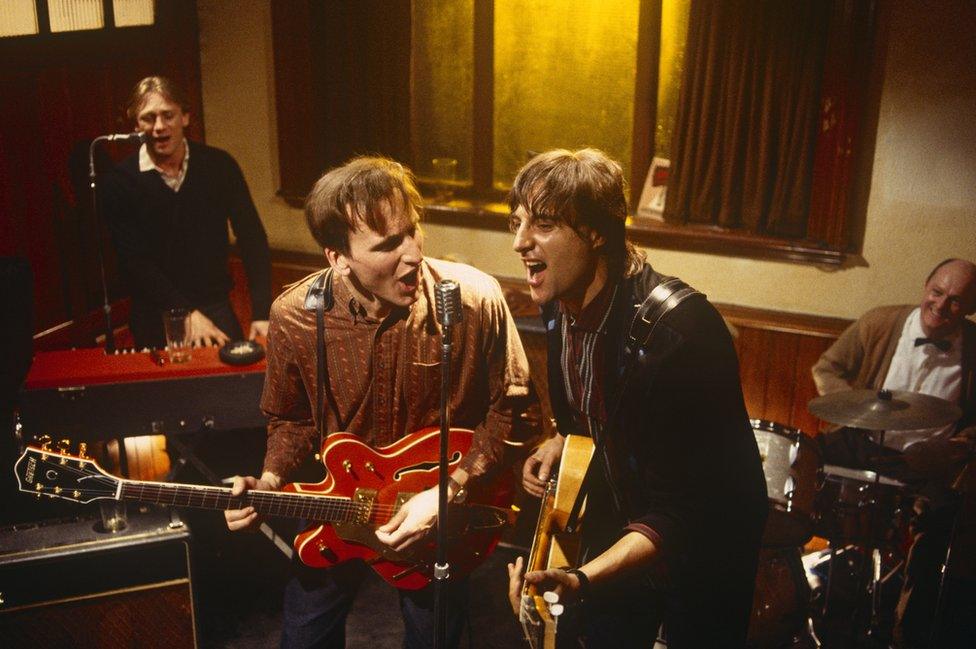

The original opening episode would have seen Geordie, Nicky and Tosker team up in a band

"I created the characters for the stage when I was 28 and didn't finish writing them until I was 44. I couldn't have imagined what would have happened to them in their 40s because I was not that old.

"That was an extraordinary thing to happen."

The series attracted weekly audiences of about six million - twice the number anticipated.

Twenty years on, though, how does he view its legacy?

"There are probably six or 10 shows in the history of British TV that stand out and I think Our Friends in the North is one of them along with Cathy Come Home and Boys From The Blackstuff.

"It captured the zeitgeist."

Andrew Collins, film editor at the Radio Times and writer of the Telly Addict blog, external, shares that view.

"Boys From The Blackstuff, which I agree is magnificent, is definitely a precursor in terms of what British television was still prepared to do. But Our Friends in the North is more ambitious, less of a time-capsule.

"Nothing is perfect in this world and Our Friends in the North's wigs let us down," jokes Eccleston

"By the time it became a TV drama, Thatcherism had run its course, albeit having reshaped Britain and not necessarily in a good way. Perhaps this was a better time to take stock and look back over 30 years to the optimism of the early 60s, which was now in some ways echoed in the early 90s Britpop movement.

"To end it with [the Oasis song] Don't Look Back in Anger was perfect, I think. You can't really fake that kind of kismet: the song was northern, working-class and looked both to the future and the past. And it's a great track.

"Such things matter with drama that wants to tell big stories and to resonate in the here and now. The personal becomes political, and vice versa, if you can pinpoint a dramatic way of bringing the two together."

While its success "opened doors", Flannery believes budgetary concerns and an aversion to risk arguably make it more difficult now than ever for writers to translate their ideas to the screen in Britain.

"The odds are always stacked against ambitious drama," he says. "One person leaves and you lose your champion.

"And these things are expensive. For a long time, if you weren't going to get a sale in America it was pointless asking for anything to get made.

"What I call 'panto dramas' like Doctor Who and Sherlock are massively entertaining and popular, but the broad church doesn't seem to be there anymore. There's no room for an Our Friends in the North.

"I've always said it's just a posh soap opera - but it's a posh soap opera with something to say."

- Published22 October 2015

- Published30 July 2015

- Published15 December 2014

- Published30 August 2011